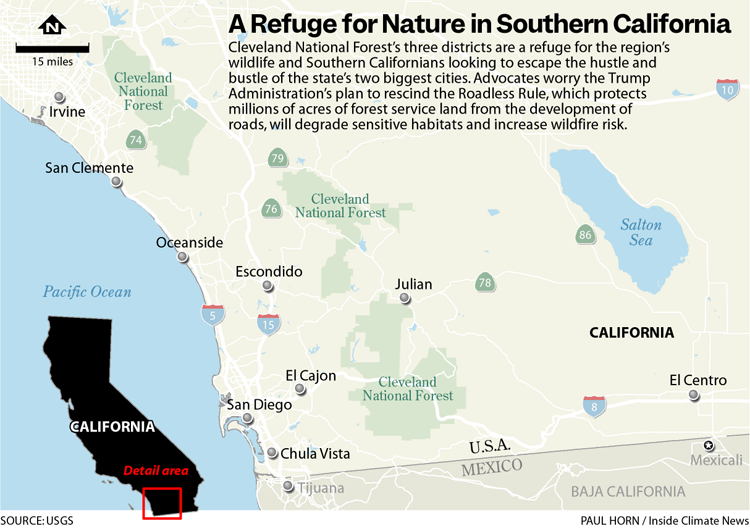

To see what Southern California looked like before millions of homes sprawled through the region, head to Cleveland National Forest. Nestled between Los Angeles and San Diego, the forest’s three districts are a refuge for the region’s wildlife and locals looking to escape the hustle and bustle of the state’s two biggest cities.

From above, a sea of homes surrounds the Santa Ana mountains—famous for the intense winds they generate—but the national forest forms a clear band of undeveloped wildlands connecting the southernmost peaks of the state’s Coast Ranges to the northern Mojave Desert.

But a nearly 25-year-old federal rule protecting the area, along with portions of many other national forests across the country, may soon be rescinded, paving the way for more development and increasing wildfire risk in some of the nation’s last remote woodlands and wilderness areas.

In June, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins announced that the USDA, which oversees the U.S. Forest Service, planned to repeal the Roadless Rule that has prevented new roads from being cut into nearly 60 million acres of national forests. Rollins has called the 2001 rule a “disastrous” policy that has created “absurd obstacles” to management of public lands managed by the U.S. Forest Service, which has made communities more vulnerable to wildfires while restricting logging and development in rural areas of the West.

“There’s no doubt about it, we are continuing to be aggressive in our efforts to increase

American timber production in line with President Trump’s agenda,” Rollins said during a speech at the Western Governors’ Association conference on June 23, where she announced plans to rescind the Roadless Rule. “These actions are essential, not just to revive our struggling forestry industry, but to save lives [from wildfires].”

The science, however, shows otherwise, say critics of the USDA’s planned rescission of the rule. Researchers have found that roads increase the likelihood of wildfires in the areas they access. And while the Trump administration claims the Roadless Rule is in part to blame for the increase in the destruction from wildfires in the West, it makes no mention the growing number of communities sprawling into fire-prone landscapes, where they radically increase the number of ignitions and the amount of property vulnerable to the flames, or how global warming driven by burning fossil fuels is increasing the incidence of hot, dry and windy conditions that set the stage for wildfires like the ones that tore through Los Angeles early this year.

“We just have all of this evidence to show that if you put more roads in there, you’re going to get more fires,” said Krystian Lahage, a public policy officer with the Mojave Desert Land Trust, a California-based conservation group.

While fires are a natural, and often beneficial, part of the forest’s ecosystem, he said, their current magnitude is not. Climate change and human activity are driving an increase in bigger, more severe blazes. In 2003, what was then the biggest wildland fire on record in California broke out in the Cleveland National Forest after a hunter became lost and lit a small fire to signal for help. It quickly spread, eventually burning 273,246 acres and killing 15 people. Twenty-two years later, the fire, named the Cedar Fire, is just the tenth largest in the state’s history.

Passed in 2001 at the end of President Bill Clinton’s second term, the Roadless Rule protected about a third of national forest lands across the country from logging and roadbuilding. The measure drew support from conservation, hunting, angling and other outdoor recreation groups.

If the roadless rule is repealed, conservation groups fear wildfires will increase in the once-protected areas, and the country’s last intact landscapes will be developed and degraded with housing, logging and other resource-extraction operations. And, they note, the rescission of the Roadless Rule is just the latest in a series of actions from Republicans and the Trump administration to roll back protections for public lands in an effort to further open them up to extraction and development.

A Bird’s-eye View

While growing up in Huntington Beach, Lahage’s introduction to the outdoors was in the Cleveland National Forest. Twenty years later, on a small plane arranged by Ecoflight, a nonprofit that takes policymakers, environmental organizations, journalists and other stakeholders on aerial tours over significant landscapes to provide a birds-eye view of issues affecting the area, Lahage explained that “whatever your taste in nature, you can find it here.”

Hunting is common in the Cleveland National Forest, anglers flock to Santiago Creek for trout fishing and there are miles of trails popular with hikers, mountain bikers and horseback riders, including the Pacific Crest Trail that runs from Canada to Mexico. Perhaps most important is the biodiversity of the Roadless Area, which provides habitat and critical migration corridors for mountain lions, coyotes, mule deer and even the occasional California condor. The roadless area also provides a buffer around the Wilderness Areas deeper in the national forest—islands of pristine land where nature is front and center.

“If we go in here and log or if we go in here and develop the roads, that can’t be undone,” Lahage said. “The fractures to the environment can’t be undone, and we lose out, not just on this resource for people, but it’s another strike for the biodiversity crisis.”

Cleveland National Forest lacks the old-growth timber suitable for logging found in other parts of the country. Instead, it’s filled with chaparral and small oak trees, making it unlikely that any logging operations will utilize new roads cut into the forest. Instead, Lahage worries that overturning the Roadless Rule will allow the kind of access to the woods that will increase the number of wildfire ignitions in the area and the potential for big fires that could threaten the nearby communities. And new roads in the woods could pave the way for the privatization of portions of the forest.

Public Support for Roadless Forests

Americans across the country have spoken out in support of the Roadless Rule. An analysis by the Center for Western Priorities found that more than 99 percent of the 183,000 comments submitted during the public comment period for the proposal to rescind the rule opposed the action. The comment period ended September 19, with a draft environmental impact statement expected for March, and a final decision made later next year.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“Across state lines and party lines, Americans spoke with one voice to tell President Trump to stop this attack on America’s forests,” Aaron Weiss, the deputy director for the Center for Western Priorities, said in a statement announcing the analysis. “Public support for the Roadless Rule has only increased in the quarter century it has been in place. During that time, the rule has protected countless watersheds, habitats, as well as provided incredible backcountry recreation opportunities to the nation.”

Public lands are incredibly important to Orange County, said Al Tello, a field representative for Orange County Supervisor Don Wagner, whose district borders the national forest. Tello joined the EcoFlight aerial tour to learn about the proposed rescission of the Roadless Rule.

“You go out there and you think you’re out in the middle of nowhere, and you’re literally a 20- to 25-minute drive from Irvine,” Tello said. “That’s what’s so stunning.”

Back on the ground in Cleveland National Forest, it’s easy to forget that it’s in the middle of one of the country’s densest areas of urban development.

The Tin Mine Canyon Trail heads toward the roadless area from a trailhead less than a mile from the sprawling edge of Corona, but nothing of the city soundscape can be heard there. Instead, on an early fall morning, coveys of California quails crossed the path, scores of other birds like the northern mockingbird sang in the tree canopies and grasshoppers chirped in the surrounding scrub.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,