From our collaborating partner “Living on Earth,” public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by producer Aynsley O’Neill with Mike Fitz, the creator of Fat Bear Week.

Every year, Katmai National Park and Preserve in southwest Alaska hosts perhaps the fiercest bracket competition the animal world has ever seen.

Fat Bear Week showcases the park’s famous brown bears, who have spent all summer feasting on fish to get ready for winter hibernation. Voters from around the world champion their favorites, sometimes on size alone, but also on the individual stories that you can follow by watching the online webcam footage.

Mike Fitz is the creator of Fat Bear Week, which he started when he was a park ranger at Katmai National Park. He now works as the resident naturalist for explore.org, which hosts Fat Bear Week. He’s also written a book on these corpulent creatures, “The Bears of Brooks Falls: Wildlife and Survival on Alaska’s Brooks River.” This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

AYNSLEY O’NEILL: The world has been celebrating Fat Bear Week now for over a decade. How did you first come up with the idea for a contest like this back in 2014?

MIKE FITZ: Bears need to get fat to survive. Fat is the fuel that powers their ability to survive winter hibernation. When I was a ranger at Katmai, we would see many of the same bears in early summer and in late summer, and we would see their body mass changes. That was one of the things that we always talked about with the park visitors.

But in late September 2014, I was browsing webcam comments on explore.org, and I saw a pair of screen captures from the webcams of the same bear from an early summer photo and a late summer photo, and one person remarked, ‘Hey, look how fat this bear got.’

Something in my brain clicked at that moment, and I thought, wouldn’t it be fun if we allowed the webcam audience to decide who was the fattest and most successful Brooks River bear of the year? So we came up with this idea for a thing called Fat Bear Tuesday. It was a one-day tournament. We put it on Katmai’s Facebook page, people voted with their reactions or likes, and that day, I decided this needs to be expanded into a whole week to give more people the opportunity to participate. And that’s how Fat Bear Week was born.

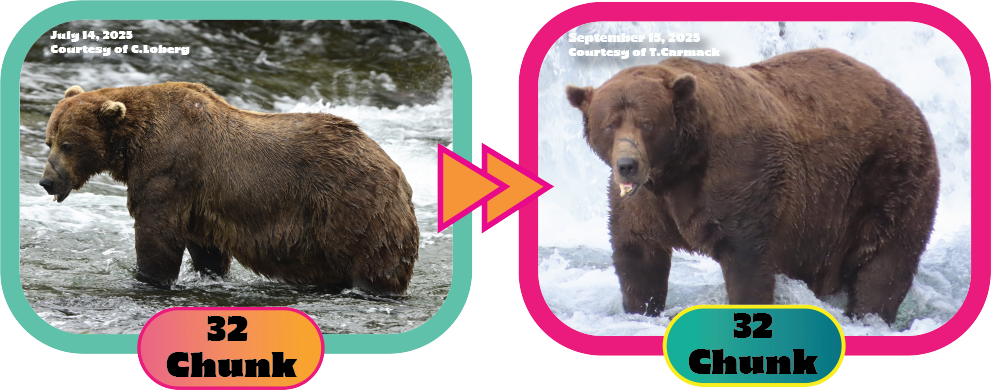

O’NEILL: The winner of this year’s Fat Bear Week was 32 Chunk. What can you tell us about him?

FITZ: Chunk is one of the largest bears at Brooks River, and has been so for a number of years. Chunk is a big bear, a 1,200-pounder at least. He’s probably fatter than that, but we don’t know for sure—but at least 1,200 pounds.

He’s one of the more dominant bears at the river. This year, however, he had a pretty severe setback in June when he broke his jaw. We don’t know how he broke his jaw, but the timing of it and the nature of the injury strongly suggest he broke it in a fight with another bear. He’s had to deal with the pain, the suffering, but Chunk is powering through it, and he’s done so throughout the year. He’s gotten really, really fat, and he’s done remarkably well for himself this year. I think with his resilience, his perseverance, that story resonated with a lot of Fat Bear Week voters. And Chunk has been the runner-up, I think, the past two years in 2023 and 2024, so this seemed like it was his year.

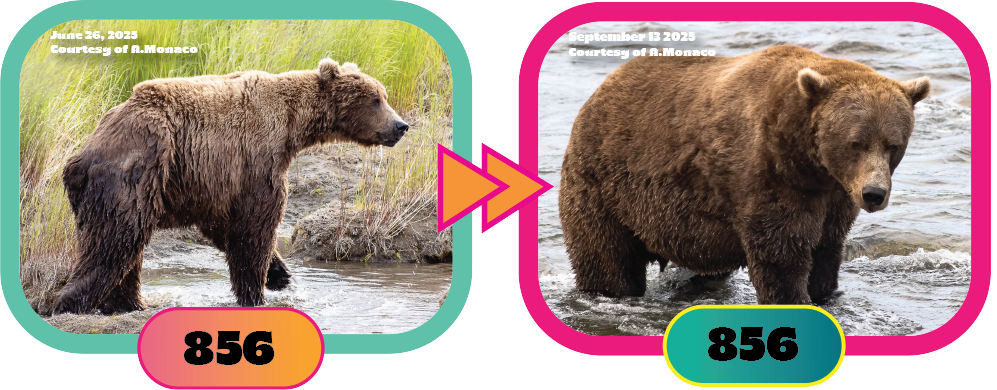

O’NEILL: Can you tell us about the runner-up?

FITZ: The story of 856 resonated with people because he’s an older adult male, so he can’t compete like he had in the past, and he was the river’s formerly most dominant bear. He became hyper dominant in 2011 and was at the very tippy top of the bear hierarchy at the river, and he held that position for more than a decade.

O’NEILL: I’m curious why some of these bears, like Chunk, get names and others are just known by numbers.

FITZ: There’s no official nicknaming process with the national park staff at Katmai. Some of the bears just get nicknames over time informally. Chunk got his nickname just as a memory aid for the biologists who were identifying bears. 856 has never had a nickname, and I can’t actually imagine calling him anything else than 8-5-6 or 856.He’s just always going to be that number for me.

O’NEILL: What exactly are these bears eating in order to get so big?

FITZ: Brown bears are omnivores, just like people, so they eat a wide variety of foods, but in Katmai National Park, salmon are especially important to brown bears, so they have a higher percentage of meat and protein in their diet compared to a lot of brown and grizzly bears throughout North America. That’s one reason why they can grow so large is because they have access to ample runs and large runs of salmon. And salmon are such a great food for bears because they’re not only high in protein, but they’re also very high in fat as well.

O’NEILL: How much salmon do these bears tend to eat on a daily basis?

FITZ: Depends on the bear, depends on the day it’s having, depends on the amount of fish that are moving through the river that day. But on a good day, a bear can easily catch 20 to 30 salmon. I think the record that I saw personally was a bear that ate like 42 salmon in about five hours. These aren’t small fish, either: a sockeye salmon can average about five pounds in Brooks River.

O’NEILL: In order to support that volume, it sounds like the salmon run must do pretty well each year. How was it this year?

FITZ: This year’s salmon run in Brooks River was exceptional. We saw wall-to-wall salmon from early July until the middle of August, and hundreds of salmon jumping the waterfall every minute. It was really incredible to watch. And Bristol Bay, the Katmai region, is home to the last great salmon run left on Earth.

One of the things that was special about Brooks River this year, though, was that there were so many fish in the river that the bears were essentially released from food competition. In a normal year when there are fewer salmon, or maybe just waves of salmon moving into the river, bears will go to Brooks Falls, and they’ll compete for the most productive fishing spots. We didn’t really see that in early summer this year, because there was no single good fishing spot.

Fishing was good everywhere along the river, and we saw bears expressing a lot more tolerance, a lot more playful activity between bears. (You can watch a live video feed of the bears here.) To me, that was another demonstration of their behavioral flexibility, their behavioral plasticity. They are adaptable creatures. They’re very smart animals, very sentient and aware of their environment.

O’NEILL: What happens to the parts of the salmon that these bears discard?

FITZ: There’s no waste in nature. The discarded parts of the salmon are cleaned up by scavengers. Maybe that’s a hungrier bear downstream. Maybe that’s a bald eagle, maybe it’s a gull.

One of the more fascinating aspects of this dynamic as well is that plants grow faster in areas where salmon are coming back into these watersheds. Bears are maybe carrying salmon carcasses into the forest or the marshes along a river, for instance. They’re also carrying salmon nutrients through their digestive system, so they will leave deposits in their scat out in the forest, or they’ll urinate in the forest. And that helps to boost the productivity of plant life around these watersheds as well. Salmon are really kind of like the gift that keeps giving.

O’NEILL: What are these bears going to be doing now? Walk us through the beginning of fall to next summer.

FITZ: They’re storing up basically a winter’s worth of food to survive that period of time where they have no access to food. They’re going to be concentrating more and more on eating over the next several weeks, though their metabolism is starting to ramp down. It’s a really slow transition down into their hibernation mode. Their appetite will decline. They’ll eventually wander off to their dens. They will build and construct their dens on steep slopes that collect and hold a lot of snow.

In Katmai, they’re basically just digging a den straight into the earth, straight into a hillside, and then they’ll eventually go in there and begin hibernating. Generally it’s in November for most bears in Katmai, although it ranges from maybe like late October into December, when they begin hibernation.

O’NEILL: To what extent are you able to monitor them during their hibernation period? And I don’t just mean you and the scientists who work with them, but what about the public? Are there any live cams that we’d be able to use to check up on our favorite bears? Or do we just have to wait until next year?

FITZ: We’re gonna have to wait until next year. In Katmai National Park, the locations of bear dens are too unpredictable for us to say, hey, let’s put a cam in this location.

But we’ve learned a lot from webcam observations of bears in dens in other places. And then also, sort of like the miniaturization of technology has allowed scientists elsewhere, like in Scandinavia, to actually implant heart rate monitors and GPS collars and things like that on brown bears, to know where they’re denning, and then you can check and see you know what the heart rate monitors are telling us about brown bear physiology and metabolism inside of the den.

O’NEILL: The world is facing a few ecological crises: climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution. How are the bears faring with these issues on the rise?

FITZ: In Katmai National Park, they’re doing really well, and that’s largely because the ecosystem there is intact. Katmai is a very remote national park. It’s almost exclusively undeveloped. There’s hardly any trails. You have to fly or take a boat to get there. So the watersheds are healthy. They’re unengineered.

The salmon runs right now are ample, but that doesn’t mean that they’re not facing threats due to climate change. The hydrology of the park is certainly changing. Glaciers are melting. Ice cover along the volcanoes has declined significantly over the last century. We know that the lakes and rivers are getting warmer. We know that the oceans are getting more acidic as they absorb CO2 from the atmosphere. All of those things have this significant potential to disrupt the sockeye salmon run in Bristol Bay. So they’re doing well in some respects, but the future does pose some significant challenges for them.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowO’NEILL: It’s good to hear that these bears are doing pretty well, all things considered. But for fans who pay attention, maybe just during Fat Bear Week, what can they do the rest of the year to show some support or appreciation for these bears?

FITZ: There are several things that people can do. One of the things that we can do is just share the story of Katmai and Bristol Bay and the Brooks River bears and the Fat Bear Week bears with other people. That’s really special. With the biodiversity loss and the extinction crisis happening around the world, often we get overwhelmed with these doom and gloom stories, but there’s a lot to celebrate. There’s a lot to save out there. And I think we can look at Bristol Bay and Katmai as one of those examples of things that we can work toward in other places as well.

O’NEILL: In addition to being the creator of Fat Bear Week and an author, you currently work as a naturalist with something called explore.org. Tell us a little bit about your role there.

FITZ: I’m the resident naturalist with explore.org; we are a philanthropic organization that specializes in live cams of animals in nature. I think we have something like 190 live cams around the world, so there’s always something to watch.

In the morning, before the brown bear cams in Katmai go online, I might go to Africa. I was actually watching hummingbirds at a feeder in southern Arizona this morning. It’s free. There’s no advertisements. There’s no requirement for you to sign up for anything to utilize explore.org and it’s really an opportunity for us to see unedited nature.

My role with explore.org is to be an online interpreter for the wildlife. Due to my experience working as a park ranger in Katmai, I do a lot of programs about brown bears and salmon in conjunction with the park rangers at Katmai throughout the summer and fall. During the rest of the year, though, I might be interviewing people about the wildlife that they are trying to protect or work with. We have some seasonal cameras that come on in the winter, like for manatees in Florida. So I might be talking with Save the Manatee Club or one of our other great partner organizations about the wildlife work that they do.

It’s a rewarding job for me, because I get to learn so much, so it helps to stimulate my curiosity. But at the same time, I feel very fortunate to be able to share these experiences with people all over the world.

O’NEILL: How do you feel that your work as a naturalist has been informed by or resulted from these experiences working with bears in Katmai?

FITZ: When I went to Katmai, I was largely ignorant of how wild animals are individuals. They compose a population, right? But just like us, they’re individuals in their own ways. My experience working as a ranger helped me understand that parks really do matter to everybody. They’re valuable spaces to us, whether we have the opportunity to visit them in person.

I encourage everybody to get out into nature as much as you can. But also, there’s these other nature-based experiences on the internet that are extraordinarily valuable as well, and I hope that through webcams and technology, we can share more of these amazing places with more people.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,