Forever War, Part 1: This story is published in partnership with The Assembly and with WHQR, a nonprofit radio station and NPR affiliate in Wilmington. It is the first in a series of stories about the PFAS crisis in North Carolina.

Listen to an audio version of this story below.

OAK ISLAND, N.C.—Emily Donovan stood before 100 people in the pews at Ocean View United Methodist Church in a small seaside town in Brunswick County, North Carolina. It was May, the start of beach season. She had invited a scientist to speak about the astronomical levels of PFAS—nicknamed “forever chemicals”—that had been detected in sea foam four miles away.

But before she began her presentation, Donovan, a co-founder of Clean Cape Fear, had to deliver some bad news. That morning, Lee Zeldin, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency administrator appointed by President Donald Trump, had announced his intention to rescind drinking water regulations for several types of PFAS compounds.

The rollbacks included GenX, one of dozens that have contaminated the region’s drinking water and have been linked to disorders of the liver, kidneys and the immune system, as well as low birth weight and cancer.

Donovan felt devastated and enraged.

“Churches in Brunswick County baptize their babies in PFAS-contaminated tap water,” Donovan told the crowd. “We fought so hard. And now our hard work is getting rolled back.”

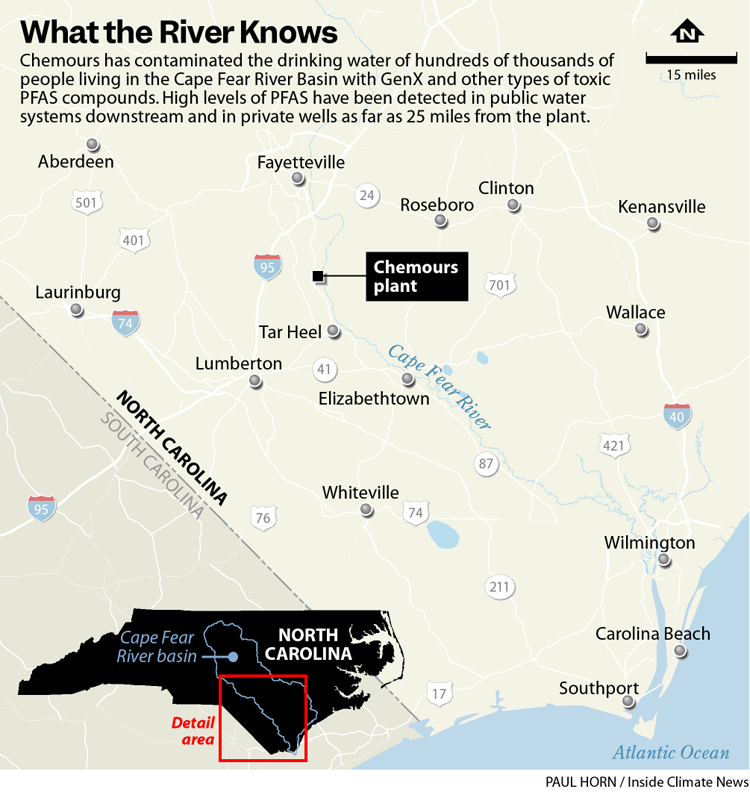

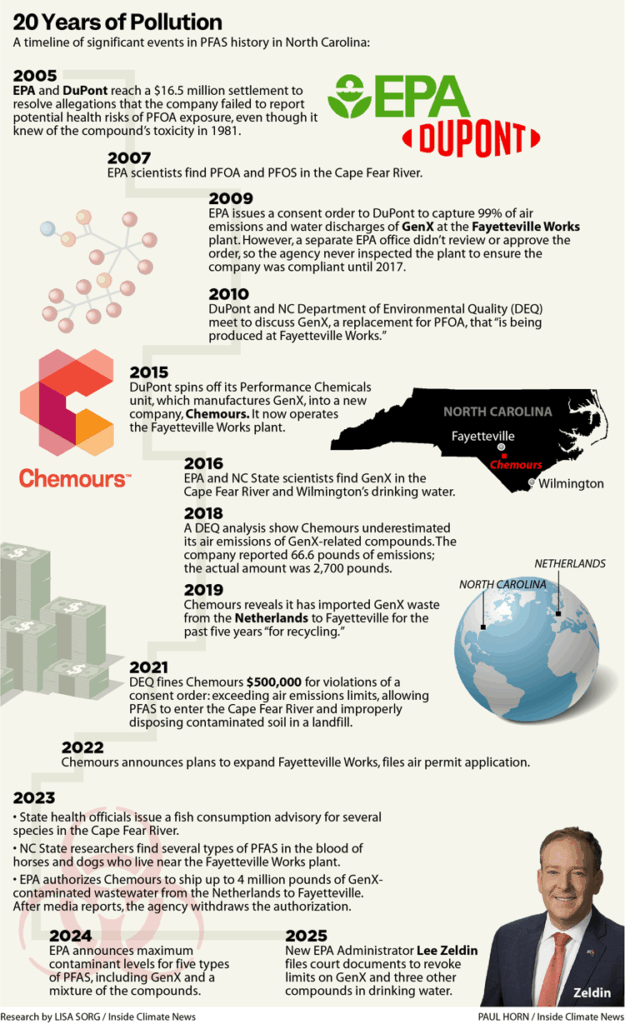

In 2013, scientists first discovered several types of PFAS in the Lower Cape Fear River, the drinking water source for several utilities in the region. The insidious chemicals were eluding traditional water treatment systems and flowing through the taps of hundreds of thousands of people.

The scientists traced many of the compounds to Chemours’ Fayetteville Works plant, 80 miles upstream. State and federal documents show that for 40 years Chemours and its predecessor, DuPont had been quietly tainting the drinking water of a half-million North Carolinians with high levels of toxic PFAS.

It took several years for that information to reach the public, but once it did, Donovan and her fellow environmental activists, as well as public interest lawyers, state legislators and local residents, started urging the EPA and the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality to regulate the compounds.

Many went to Congress and to court. Clean Cape Fear pleaded its case to the United Nations special rapporteurs on human rights, who concluded last year that PFAS contamination coming from the Chemours facility constituted “a business-related human rights abuse.”

Meanwhile, the scope of the contamination expanded throughout the state. Scientists found the compounds in fresh vegetables and fish, eggs and beer. Pine needles, honey and house dust. Landfills, compost and sewage sludge.

Blood of horses. Blood of dogs. Their own blood.

Finally, the environmental advocates prevailed. In 2024, Michael Regan, North Carolina’s former top environmental regulator who’d become President Joe Biden’s EPA administrator, announced his agency would regulate five types of PFAS, including GenX, in drinking water.

The celebration was brief.

Now, here was Trump back in the White House, and Zeldin, with support from the chemical industry, was dismantling those hard-won protections.

And now, here were North Carolinians, prepared to battle anew for the health of their communities. To stop Chemours from dumping GenX in landfills. To force the company to pay for drinking water it had defiled. To halt the expansion of the Fayetteville Works plant.

“This is a motivator, not a deflator,” Donovan said, a few weeks after Zeldin’s announcement. “We’re going to continue to fight this, now, more than ever.”

2013-2016: A Movement Is Born

The Cape Fear River begins 200 miles upstream from Wilmington, at the confluence of the Haw and the Deep rivers.

On its journey to the Atlantic Ocean, the Cape Fear rambles through forests of loblolly pine and courses under plains of concrete. About halfway to the sea, where the river grazes Chemours’ Fayetteville Works plant, the company was sending PFAS into the waterway.

Had it not been for Detlef Knappe and several scientists, including Mark Strynar and Andy Lindstrom of the EPA, Chemours could still be doing so.

Knappe is a distinguished professor of civil, construction and environmental engineering at NC State University in Raleigh. He grew up in southern Germany in the small town of Freudenstadt, which translates to “City of Joy.”

Now a lean, ruddy man in his 50s, Knappe has retained shards of his German accent, but its edges have been softened, like rocks weathered by water. He is quiet and modest, and never boasts that he was among the scientists whose findings launched an environmental movement.

In 2013, Knappe and the EPA scientists were curious about a new chemical that DuPont had been manufacturing at Fayetteville Works. It was a replacement for PFOA, another “forever chemical” used in stain-resistant carpet, waterproof apparel and nonstick cookware, which the company agreed to phase out by 2015 due to its health risks.

Coincidentally, the EPA scientists soon stumbled across a pamphlet from DuPont that named the mystery chemical: GenX.

Knappe had preserved water samples from the Cape Fear River for a different project. When the scientists analyzed the samples for GenX, they found average levels in Wilmington at 600 parts per trillion, with spikes reaching 4,500 ppt.

“We all felt that was really high,” Knappe said. “But how do you communicate that information? There’s this mystery chemical, GenX, and we weren’t aware of much information about its toxicity.”

The scientists were right: The levels were as much as 450 times what later became the drinking water standard. Their analysis found GenX was passing through the treatment system at the Sweeney Water Treatment Plant in Wilmington. Residents were drinking, bathing and playing in contaminated water.

As the scientists worked on a paper that contained their new findings, the EPA lowered the health advisory for PFOA and another forever chemical, PFOS, to 70 ppt. While the advisory didn’t apply to GenX, the scientists were concerned about the potential health effects of the new compound, given its high levels in the drinking water.

We have to publish that paper now, Knappe thought.

When the paper came out in November 2016, he shared the findings with state regulators and utilities, but without toxicity data, no one knew what to make of it.

Then a freelance reporter for the Star-News of Wilmington, Vaughn Hagerty, happened upon the scientific paper online. On June 6, 2017, he broke the story of the scientists’ findings about GenX in the city’s drinking water.

People protested in the streets. Residents mobilized on Facebook.

“What was surprising and gratifying was the impact that article made,” Knappe said. “And how, maybe for a moment, politics stopped.”

2017-2018: Clean Cape Fear

Donovan is in her 40s, with chin-length, dark brown hair and glasses. At 5 foot 10, she is swan-like and often towers over a crowd. She worked in corporate marketing for a decade, then moved to Leland, in Brunswick County, from Charlotte with her husband in 2009. At the time, she was pregnant with twins, a boy and girl.

She became a stay-at-home mom and for seven years taught Bible study at Little Chapel on the Boardwalk in Wrightsville Beach. After noticing some children were praying for the health of their loved ones, Donovan said she heard God call her to become an environmental advocate.

In June, she and several concerned residents, including Cape Fear Riverkeeper Kemp Burdette, social activist and retired obstetrician Dr. Jessica Cannon, and former Wilmington Mayor Harper Peterson, gathered at Peterson’s wooden dining room table to discuss how to handle the crisis.

The demonstrations had been powerful, but diffuse. The activists decided they had to channel the public’s anxiety into a coherent movement. They called the group Clean Cape Fear.

In Raleigh, Michael Regan had been the head of the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality for just six months. He was homegrown, having been raised in Goldsboro, about an hour southeast of the capital. He graduated from the historically Black N.C. A&T University in Greensboro before heading to Washington, D.C., for an advanced degree in public administration.

Water pollution and obscure contaminants weren’t Regan’s specialty. He had worked in air quality and clean energy programs at the EPA and later at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Now as head of DEQ, Regan was facing the type of daunting challenge that can define a leader’s legacy.

2017-2018: Stymied at the Legislature

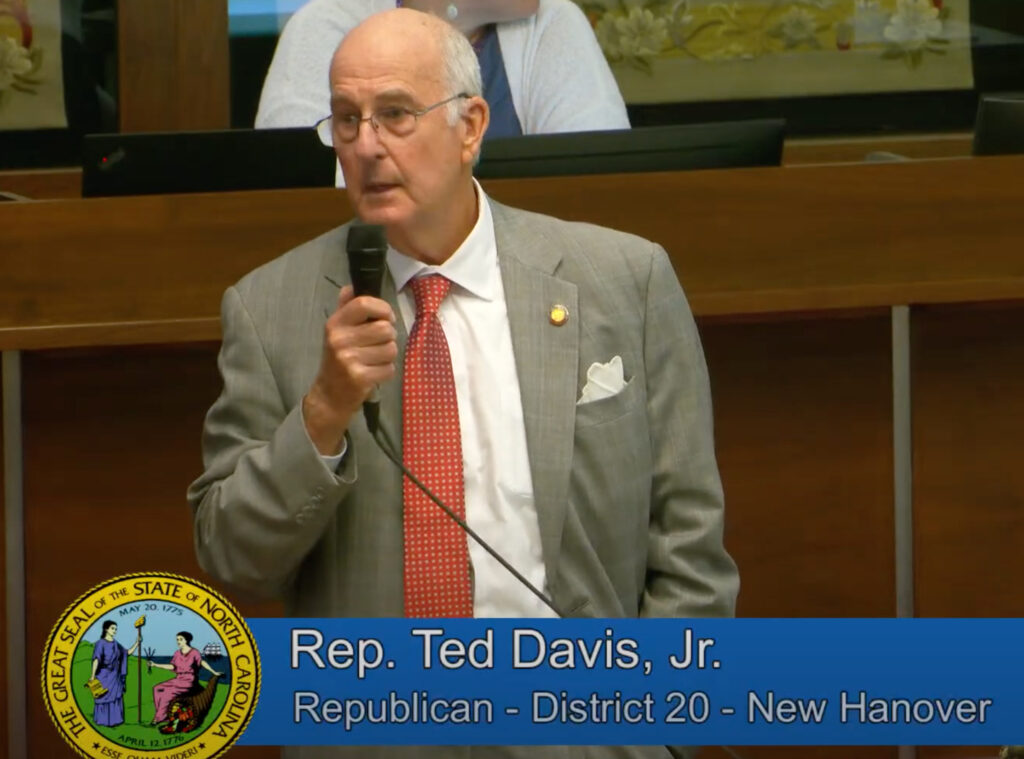

Republican State Rep. Ted Davis Jr., is 75, a trim man with wire-rimmed glasses. A former state and federal prosecutor, he grew up in New Hanover County and drank water from the Cape Fear River for most of his life.

Like most people, Davis knew nothing about PFAS. But as an advisory member of the Joint Environmental Review Commission, he hoped his colleagues would support funding for local governments to address pollutants, monitor the river’s quality and hold hearings on the PFAS contamination.

Yet after a contentious Environmental Review Commission meeting in 2017, the Senate declined to hold another hearing.

Undeterred, Davis approached Republican Tim Moore, then the House speaker, and asked to form a special committee. “I said, ‘Tim, I don’t give a damn whether the Senate is going to support it or not,’” Davis recalled. “‘This is too important.’”

Davis, the senior chairman of the resulting House Select Committee on North Carolina River Quality, presided over seven lengthy meetings with toxicologists, state regulators, scientists and other experts.

Still, several legislators fell in line with the industry’s talking points. State Rep. William Brisson, a former Democrat from Bladen County who had switched parties, downplayed the compounds’ toxicity. “It’s not like the mice fell over dead when they were injected with GenX,” he said at the committee hearing.

Those hearings prompted Davis to introduce the Water Safety Act. But only one of the bill’s provisions became law: A $450,000 allocation to the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority to test the finished drinking water and to install a temporary advanced treatment system was eventually folded into the state budget.

“We all drink the water and we breathe the air, and some of us just don’t seem to care about cleaning it up.”

— State Rep. Deb Butler

On the Democratic side, state Rep. Deb Butler, an attorney who represents New Hanover County, was having even less luck than Davis in advancing PFAS legislation. Some of her bills called for an outright ban on PFAS, including their use in firefighting foam and consumer packaging. Most of the measures died in committee; some never got a hearing.

“One of the things I’ve learned in the last eight years is that things that shouldn’t be politicized are, and the environment is one of them,” Butler said earlier this summer. “We all drink the water and we breathe the air, and some of us just don’t seem to care about cleaning it up.”

2018: A Prayer Circle and Cancer

Brian Long, then the plant manager at Fayetteville Works, paced the floor before more than 100 people at Faith Tabernacle Christian Center. He wore an orange Chemours pin on the lapel of his sport jacket.

It was a cloudy evening in June 2018. The company was hosting a public event in St. Pauls, a small town two hours from Wilmington, to assuage the community’s fears about GenX.

“There’s been a lot reported on this compound,” Long told the frustrated, angry crowd. “We have decades of evidence and studies that suggest this compound—at the levels we see in our environment—do not cause health risks.”

EPA and academic scientists soon found that even at low levels, GenX was associated with harm to the thyroid, liver and kidneys.

Rates of thyroid cancer declined in New Hanover and Brunswick counties, according to National Cancer Institute data from 2017 to 2021, the most recent figures available. However, those two counties still rank second and fifth, respectively, for thyroid cancer rates in North Carolina, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show.

Kidney cancer rates rose in Brunswick and Pender counties during that time, according to federal data. Pender County leads North Carolina in rates of testicular cancer, also associated with GenX exposure.

Local residents had begun reporting their experiences with cancer and other health problems. Some risk factors, such as age and genetics, make it difficult to establish causation between their illnesses and exposure to PFAS. Yet thyroid, testicular, brain and other cancers have been linked to the compounds.

Several advocates’ families were touched by disorders they felt might have been linked to PFAS exposure. Donovan’s husband, David, had been diagnosed with a benign brain tumor that caused him to go blind until a surgeon removed it.

Dana Sargent, then with Cape Fear River Watch, was worried about her older brother, Grant Raymond, diagnosed nine months before with a malignant brain tumor. He had been exposed to high levels of PFAS while a U.S. Marine and throughout his career as a Chicago firefighter. Doctors had given him less than five years to live. He was only 45.

Sargent, now 51, is from the Chicago area and arrived in North Carolina by way of California and Washington, D.C. She is short and petite, with long, flowing brown hair. She specializes in research, but her other quality is bluntness.

She attended the meeting, which began with a prayer circle that included Chemours. “It was asinine and repulsive to hold a meeting in rural North Carolina, in a church—to help shut people up,” she said. “They knew what they were doing.”

One man in the second row told Long that because of contamination in his neighborhood, he couldn’t sell his house.

“I understand you’re frustrated,” Long said, three times.

The man became angry, and as law enforcement led him out of the church, he told Long, “You have defiled the house of God.”

2018-2019: Chemours Cuts a Deal

Here’s Kemp Burdette, the Cape Fear Riverkeeper, on how to snag an alligator to test its blood for PFAS:

Get a treble hook, the kind used to catch a marlin.

Cast the rod over the alligator, which should be lying in the water. Reel in the line until the hook reaches the alligator, then jerk it with all your strength.

Steer the tired alligator to the bank.

Then, everyone jumps on the alligator (multiple humans, if possible).

Finally, tape the alligator’s mouth shut. Stick a 20-gauge needle at the base of its skull to draw 15 milliliters of blood.

Burdette helped NC State University and EPA scientists apprehend alligators in the Cape Fear River and several nearby lakes to test their blood for PFAS. Alligators spend their long lives in water often polluted with chemicals; they can serve as models for detecting human health problems caused by contamination.

The scientists sampled the blood of 75 alligators and found 14 different PFAS at concentrations similar to levels found in the blood of Wilmington residents. High levels of PFOS would later be found in several species of freshwater fish, prompting the state health department to advise people to eat no more than seven servings a year. Pregnant women should eat none.

It had been more than a year since the contamination had become public, and Burdette was fed up with what he viewed as DEQ’s inertia and Chemours’ negligence. He pestered the attorneys at the Southern Environmental Law Center: We’ve got to do something.

Geoff Gisler, then a senior attorney at SELC, began to strategize, but it soon became apparent to him what needed to happen.

“We sued,” Burdette said.

SELC alleged DEQ was failing to uphold the North Carolina Constitution, a section of which obligates the agency to protect the environment and human health from the effects of pollution. The law center also filed suit against Chemours, alleging it had violated the federal Clean Water Act by discharging PFAS, including GenX, into the Cape Fear River.

By the fall of 2018, DEQ and Chemours were trying to make a deal.

“In some ways it was a very sterile process,” Burdette recalled. “But it was also very tense. I felt like we didn’t need to do a whole lot of negotiating because we were right. They had poisoned the drinking water supply, and the state had let them do it. I didn’t want to compromise, and I think we did as little of that as we possibly could.”

By February 2019, the parties had crafted a consent order. Among the many provisions in the 46-page document was a requirement for the company to sample private wells for a dozen types of PFAS and to provide clean water to households whose wells were contaminated above certain thresholds.

No longer could Chemours discharge wastewater into the river as part of its manufacturing processes. No longer could the company expel hundreds of tons of GenX from its smokestacks; it had to reduce the emissions by 99.9 percent.

DEQ, too, had specific duties to hold Chemours accountable, including levying a record $13 million civil penalty.

“I think it’s been a tremendous success,” Gisler said in a recent interview. “It was never the final word and would never fix all the problems, but it’s a big step in the right direction. It’s our view that the polluter has to pay, and that hasn’t been happening, because the state and the EPA had not been enforcing it.”

In retrospect, Sargent, the former head of Cape Fear River Watch, wishes the consent order had been tougher. But when the document was finalized, few, if anyone, could foresee the scientific advances in detection methods.

“We didn’t know then that there were 350 types of PFAS coming out of Chemours,” Sargent said. “There’s still people falling through the cracks.”

Some of those people lived in Brunswick County, where private drinking water wells and river water entering the Northwest treatment plant were contaminated. That plant served homes, businesses and schools, including the one Donovan’s young children attended.

“It sickens me to think I may have hurt my children by letting them drink that tap water,” Donovan testified before the U.S. House Oversight Subcommittee in 2019. She urged its members to pass a law banning the manufacture of the compounds. “I will forever wonder if one day that will cause them medical harm.”

At the hearing, she named her friends—Sarah, Tom, Kara—all young, all with rare or recurrent cancers.

“I am begging you to engage your humanity, to find the moral courage,” Donovan said. Her voice cracked. “To protect the most valuable economic resource—human life. Because it’s already too late for some of us.”

Some of Donovan’s friends have since died. “They left kids who are questioning their faith, wondering why God hates them so much that they gave their parents cancer and didn’t save them,” Donovan said. “The people who fought so hard to get answers of what caused their cancer died not knowing.”

Sargent’s brother, Grant, was among them. In December 2019, two years and three months after his diagnosis, his brain tumor killed him.

2021-2022: Quest for Accountability

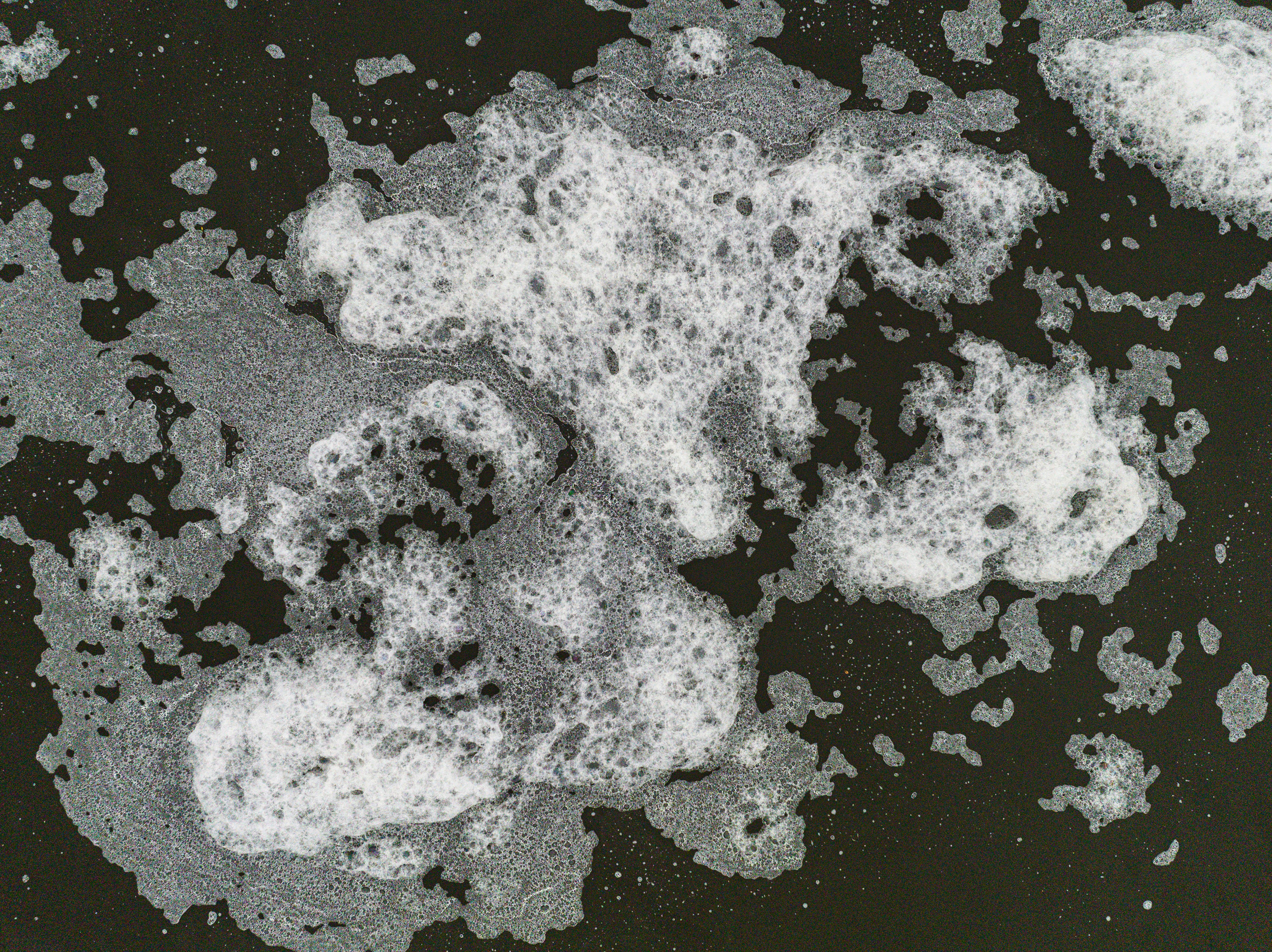

One spring day, Donovan spotted odd-looking sea foam near the Ocean Crest Pier in Oak Island, a popular spot for saltwater fishing. She learned that the best time to find the foam is after a storm or on extremely windy days, when the water is agitated. She scanned live beach video feeds and local social media chats, where people posted photos of the foam blooms.

Her sightings, as it turned out, were not isolated to the coast. State officials had seen similar foam at 15 other spots, including in Falls Lake near Raleigh and a stream in the southern foothills of the Appalachian mountains.

Eventually Donovan collected samples from 13 sites in the Cape Fear River and along the coast, including near airports and military installations, which often use firefighting foam that contains the compounds. NC State scientists began an analysis, a process that took more than a year.

In Raleigh, Davis, the Republican representative from New Hanover County who had successfully negotiated for GenX funding, was still trying to pass legislation to hold Chemours accountable. He sponsored a new bill, “PFAS Pollution and Polluter Liability,” that would require that polluters who discharged PFAS into a public water system pay for treatment costs to remove the compounds.

“I’m going to fight for my constituency,” Davis said at a hearing of the House Judiciary Committee. “If the gentleman from Chemours really wants to show they care, why don’t they pay to make the water safe from the contamination they put in that river?”

The legislation was referred to the Agriculture and Environment Committee, but, like several PFAS-related bills before it, never received a hearing.

In the same legislative session, Butler, the New Hanover County attorney now in her second term as a representative, sponsored House Bill 444. It was more aggressive than Davis’ bill and extended liability to dischargers of the compounds, not only the manufacturers.

The bill had more than 20 co-sponsors, including a Republican, Frank Iler of Brunswick County. It never received a committee hearing.

2024: At the EPA, Regan Delivers

Michael Regan had overseen North Carolina’s PFAS crisis as DEQ secretary, but a hostile legislature and an indolent EPA under the first Trump administration hamstrung much of his effort to change policy. In 2021, Biden empowered him to take steps to protect the nation’s drinking water in his new role as EPA administrator.

Yet three years had passed since Regan had joined the EPA and environmental advocates had become impatient with what they viewed as the agency’s sluggish progress on regulating PFAS.

Then, on a warm morning in April, Regan returned to North Carolina, to Fayetteville, the Cape Fear River flowing behind him.

He had arrived to announce the first legally enforceable maximum concentration levels for PFOA and PFOS at 4 parts per trillion and for GenX, PFNA and PFHxS at 10 parts per trillion. Several of the compounds were also regulated as a mixture.

Although the standards applied to only five of the 15,000 types of PFAS, they were something.

“This is the most significant action on PFAS the EPA has ever taken,” Regan said. “The result is a comprehensive and life-changing rule, one that will improve the health and vitality of so many communities across our country.”

Donovan credited the progress to the EPA’s openness to meeting with environmental advocates.

“We had conversations and incredible access to the EPA. We were given the same level of stakeholder value as the industries, maybe even more,” Donovan said. “The Regan we saw at the EPA was much more muscular than at DEQ.”

Not everyone applauded the regulations. Some conservative members of North Carolina’s Environmental Management Commission, which approves or disapproves rules proposed by DEQ, blanched at Regan’s announcement.

Michael Ellison, who was appointed to the commission by Senate President Pro Temp Phil Berger, has a history of downplaying concerns about the compounds. At a meeting that summer, Ellison asked, rhetorically, “For decades we’ve been making and discharging this stuff. How many people have died from PFAS poisoning?”

Sargent was sitting in the room. Her eyes watered. She thought of her brother and the cruelty of Ellison’s remark.

“He had no empathy,” she recalled. “He thought this was a joke.“

The American Water Works Association, a national trade group of public utilities, opposed the standards for financial reasons. The Biden administration had earmarked $1 billion to help utilities in small or disadvantaged communities cover the costs of advanced treatment to remove the compounds, yet that was a fraction of the estimated $30 billion needed for all of the nation’s affected water systems.

In North Carolina, more than 1,900 public water systems would be required to comply with the new rules by 2029. If the maximum contaminant levels had been in effect on the day of Regan’s announcement, the drinking water of at least 300 systems would exceed them.

Two months later, the trade group sued the EPA, arguing the agency hadn’t followed the legally required procedures when it made the rules.

Regan felt assured the standards could withstand a legal challenge. What he wasn’t accounting for was that in seven months Donald Trump would win a second term and that Regan’s successor would begin to brazenly repeal the standards.

May 2025: The Persistent Republican

It was after 7 p.m. on May 7, and the North Carolina House of Representatives had been debating bills for five hours. Davis, wearing a gray suit with a white pocket square and a red tie, rose from Seat No. 9 in the House chamber.

“We’ve had a long day and we’re all tired,” Davis said. “But I hope you’ll give serious consideration to what I have to say.”

Davis was a primary sponsor of a bill titled “PFAS Pollution and Polluter Liability,” modeled after his previous legislation. It was just two pages. Although it didn’t mention Chemours by name, the language was so specific, it could mean no one else.

If a PFAS manufacturer contaminated a public utility’s drinking water above federally permissible levels, it would have to pay for the installation, maintenance and operation of a treatment system to reduce concentrations in finished drinking water to comply with those limits.

“You can make all the PFAS you want,” Davis told his colleagues, “but you can’t release it into the environment.”

A last-minute amendment—key to garnering enough votes for the bill to pass—narrowed the list of eligible public water systems to those that incurred costs of more than $50 million. Those were the systems in New Hanover, Brunswick and Cumberland counties, which, without the bill, would pass the costs on to ratepayers.

“These costs should be the responsibility of the polluter,” Davis said. “It’s only fair.”

Unlike Davis’ previous PFAS legislation, this bill crossed party lines to include many Republicans. It had more than 40 co-sponsors, including some of the most progressive Democrats in the House.

The members began to vote. On the digital screens mounted in the House chamber, names of those voting yes lit up in green. After 26 seconds, nearly the entire screen was green. The bill passed 104-3.

Davis was ecstatic. It had taken five years for him to carry a Polluter Pays bill this far.

“I was tickled to death,” Davis said later. “That guy from Chemours,” seated in the gallery, “I could see he had a sick look.”

With the House in the win column, Davis now had to convince the Senate to support his legislation.

May 2025: Sea Foam and an Industry Unrestrained

A few hours before Donovan’s sea foam presentation at Ocean View United Methodist Church, Lee Zeldin, Trump’s EPA administrator, dropped the hammer. He would rescind Regan’s maximum concentration levels for GenX and three other PFAS compounds.

The EPA announcement was even more troubling in light of the results of the long-awaited study on the PFAS-laden sea foam.

Jeffrey Enders, a research assistant professor at NC State University, detected 42 types of PFAS, including some manufactured only by Chemours. One type that Chemours used as a replacement for a phased-out compound, PFO5DoA, was detected at 20,000 parts per trillion. In a different study, scientists had previously found PFO5DoA in 99 percent of the 344 Wilmington residents who provided blood samples.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowLevels of PFOS, which has not been produced in the U.S. since 2002, were found in the foam as high as 8 million ppt—the highest concentration ever reported in published scientific journals.

After Enders’ presentation, people told their personal stories.

“I live in Brunswick County and have been exposed my entire life,” one woman said, including while she was pregnant. Her drinking water well had a total PFAS level of 300 ppt.

“Now my kids are having issues,” she said, as she began to cry. “This hits hard.”

June 2025: The Senate Takes Up the Bill

Three weeks later, Davis’ bill was up for discussion in the Senate Environment Committee.

A few Republican members had warmed to regulating Chemours. “We need to run this bill,” said state Sen. Tom McInnis, a Republican whose district includes Cumberland County, another heavily contaminated area. “The folks at Chemours are notorious for not doing what’s right.”

Some Democrats thought the bill didn’t go far enough, although they agreed to support it. “You’re trying to hold the most culpable company responsible,” said Sen. Julie Mayfield of Buncombe County. “I just want people to understand this might not solve the problem.”

“I wish we could get rid of it all, but that would be herculean,” Davis said. “This is a baby step, but it might put a little bit of fear in anyone who might make PFAS.”

The tension in the room tightened. A parade of industry lobbyists began speaking to the committee, including from Chemours.

Jeff Fritz of Chemours said state regulators knew in the early 2000s that DuPont, which later spun part of its business off as Chemours, was making PFAS, including GenX. That is true. However, state records show that while regulators knew about the manufacturing, the companies failed to disclose in their discharge permits that they were sending PFAS into the Cape Fear River.

Fritz also claimed that Chemours voluntarily decided to stop discharging all PFAS. But he omitted the fact that the company did so only under scrutiny by state regulators. And that Chemours failed to stop all discharges until a second state inspection discovered GenX was still entering the river from the plant.

The bill didn’t advance. It’s eligible to be heard again next year.

September 2025: Zeldin Targets GenX for Rollback

In September, EPA Administrator Zeldin made good on his promise. The agency filed a motion in the U.S. Court of Appeals in the District of Columbia to vacate Regan’s maximum contamination levels for GenX and the three other PFAS compounds, siding with the American Water Works Association, a trade group that had opposed them.

“This is a flat-out victory for Chemours,” Donovan said. “They’re playing their game, and the Trump EPA is 100 percent caving to industry pressure.”

The argument hinges on what Zeldin alleges is an administrative misstep: When the EPA enacted the rule under Regan, it allegedly did so out of sequence.

The Safe Drinking Water Act requires the EPA to first publish a notice of intent to regulate a contaminant and seek public comment on whether it should, in fact, be regulated.

Only then can the agency propose a national primary drinking water standard and goal for the contaminant. That step requires another public comment period.

Zeldin alleges Regan’s EPA proposed and finalized a regulatory determination—as well as the regulation itself—“simultaneously and in tandem.” Without a second comment period, Zeldin argued, the agency “denied the public and the regulated community the opportunity to adequately comment on and participate in the rulemaking process.”

The EPA proposed the PFAS drinking water standards in March 2023 and provided a 60-day comment period. More than 120,000 comments were submitted, including by those now challenging the rule, according to the SELC, which also provided comments.

The agency then published a detailed 4,570-page response to those comments.

Zeldin’s EPA intends to issue a draft rule rescinding the regulations for public comment this fall; a final rule on the maximum contamination levels (MCLs) is expected next spring.

A Chemours spokesperson said the company supports the EPA’s decision. “Chemours wholly supports setting reasonable and scientifically justified MCLs,” the spokesperson said, “but getting the science right is absolutely critical, and the evidence clearly demonstrates that the previous determination for GenX is flawed.”

The EPA retained two independent scientific panels to review its findings. Over 135 pages, the 12 reviewers largely agreed with the conclusions, with minor suggestions; the agency incorporated many of them.

Chemours is cherry-picking the facts, trying to “confuse the narrative,” Donovan said.

The company cited six scientific studies conducted from 2018 to 2023 that concluded GenX’s toxic effects on rodent livers could not be extrapolated to humans because of a genetic difference in how a protein behaves between the two species.

However, four of those studies included a conflict of interest statement from the scientists, many of whom work for private consulting firms, indicating the research had been done on behalf of Chemours.

EPA scientists challenged those Chemours-backed findings. They cited examples of how the protein in question is relevant to both species; in humans, medicines are developed to target that very protein.

More than 40 concerned parties have either petitioned to intervene in the case or to file briefs in support of keeping the standards: Prominent scientists, like Linda Birnbaum, a toxicologist and former director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; attorneys general from 17 states, including Jeff Jackson of North Carolina; and environmental groups, including Cape Fear River Watch and Clean Cape Fear.

It’s uncertain whether the rescission will survive a court challenge. Under the federal backsliding rule, the EPA can’t legally repeal the standards, said Jean Zhuang, senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center. The Safe Drinking Water Act stipulates that changes to the standards can only be more protective, not less.

“What Zeldin has announced is clearly in violation of the law, in addition to harming over 100 million Americans and their drinking water,” Zhuang said. “These industries, like Chemours, are fighting these drinking water standards because then the pressure is off them to control these chemicals.”

Regardless of what happens at the federal level, a DEQ spokesperson said the agency will continue to enforce the consent order. It is also gathering data from public water systems to help them meet the drinking water standards for PFOA and PFOS by the new deadline of 2031.

Accounting for private wells and public drinking water systems, DEQ estimates 3.5 million North Carolinians are exposed to levels of PFAS above federal standards.

The same day that Zeldin filed the motion in federal court about the GenX standards, DEQ announced it was requiring Chemours to offer private well testing to an additional 14,000 residents in New Hanover, Brunswick, Columbus and Pender counties.

This brings the total to more than 200,000 homes in 10 counties that are eligible for PFAS testing. Of those, state records show more than 22,000 have been sampled and nearly 7,500 have qualified for alternate water supplies as stipulated in the consent order.

Previous testing has found PFAS 400 feet deep, nearly to bedrock, and in wells as far as 28 miles from Fayetteville Works.

DEQ says it has not yet found the contamination’s edge.

Next in the series: Local governments and residents sue Chemours. Meanwhile, PFAS and GenX are found in the landfills, sent there by the company.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,