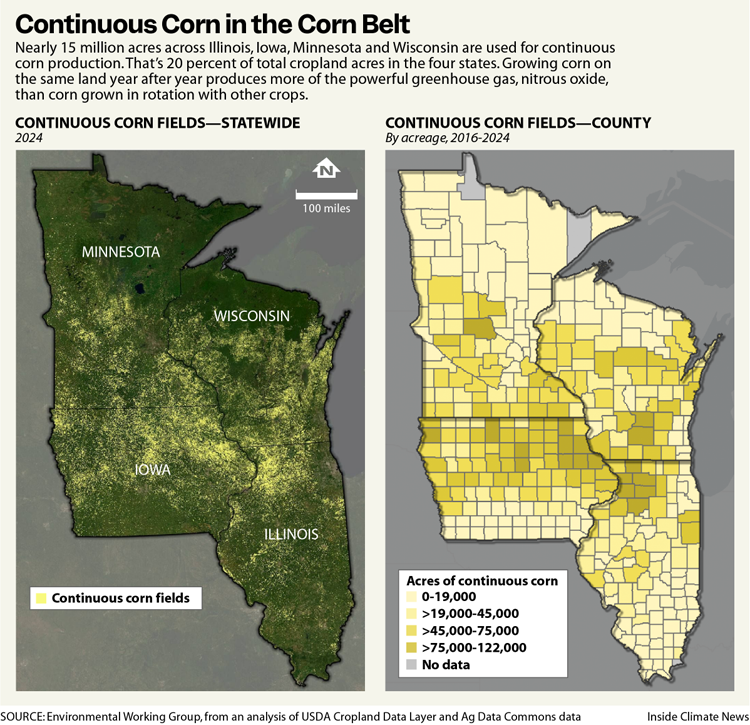

Year after year, the same 15 million acres across Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin are planted with corn.

Each August, the fibrous green leaves in those fields reach eye level. And each November, the dusty stalks are razed to stumps.

“Continuous corn,” as the growing strategy is called, allows farmers to profit from a steady demand for corn from the ethanol and livestock industries. The approach is also a major source of a potent and little-discussed greenhouse gas: nitrous oxide.

Agricultural nitrous oxide makes up only 6 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, but it traps heat in the atmosphere over 300 times as effectively as carbon dioxide and persists in the atmosphere for 120 years, compared to methane’s 8 to 12 years.

“This is something that’s not really being talked about enough, compared to methane and carbon dioxide from ag,” said Anne Schechinger, midwest director for the Environmental Working Group (EWG).

Establishing forest buffers and planting trees, shrubs, hedgerows or windbreaks on or bordering continuous corn fields could significantly reduce nitrous oxide emissions, a new report from EWG, co-authored by Schechinger, finds.

Adopting one of these four practices on just 4 percent of continuous corn acres would have an emissions reduction effect equivalent to getting more than 850,000 gas-powered cars off the road, according to the report.

“Nitrous oxide is powerful. It lasts a long time. But it’s also something that these types of conservation practices can really have an impact on reducing,” said Schechinger.

Analyzing U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture data, EWG determined that 20 percent of cropland across Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota and Wisconsin has been used to grow corn for at least three consecutive years between 2016 and 2024.

While growing the same crop without rotation is harmful to long-term soil health and biodiversity, continuous corn offers farmers short-term financial stability, explained Mark Licht, an associate professor and extension cropping systems specialist at Iowa State University.

The abundance of ethanol plants and livestock facilities throughout the Corn Belt ensures a constant demand for corn. That demand is backed by significant government subsidies for corn, Licht said.

However, growing corn year after year requires more nitrogen fertilizer than what fields cropped in the more popular corn-soy rotation need—as much as 50 more pounds of nitrogen per acre.

The subsequent buildup of nitrogen in the soil of continuous corn fields drives emissions of nitrous oxide, released as a byproduct when soil microbes convert nitrate in fertilizer to nitrogen gas or convert ammonium to nitrate.

Wider adoption of existing, simple interventions could significantly reduce agricultural nitrous oxide emissions without requiring farmers to rethink their fertilizer regimens, Schechinger said.

Using the COMET-Planner tool developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Colorado State University, which estimates how various conservation practices cut county-level emissions, Schechinger and her colleagues identified the interventions most effective at reducing emissions from areas producing continuous corn across four states.

Ranked in order of their predicted impact, the four most promising practices include creating forested buffers alongside streams, planting trees or shrubs in and around crops, planting hedgerows or “living fences” around fields and establishing forested windbreaks.

These practices reduce emissions in multiple ways, said Schechinger—both by taking small strips of land out of production and fertilization, but also by sequestering carbon. They could also help to mitigate nitrate runoff from excess fertilizer, which damages water quality and threatens aquatic ecosystems.

The conservation practices are not particularly radical, argued Schechinger. Financial and technical support for buffers, hedgerows and carbon sequestering projects has long been available to farmers through the USDA’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP), created in the 1996 Farm Bill.

EQIP, the nation’s flagship farm conservation program, has an annual budget of nearly $2 billion and establishes short-term cost-sharing contracts with farmers who integrate conservation goals into their working land.

An updated “skinny farm bill” could prioritize EQIP support for practices that reduce emissions, said Schechinger, for example, by extending the length of EQIP contracts and shouldering a larger portion of the cost-sharing for particularly climate beneficial practices.

Nitrous oxide has been largely overshadowed by methane in discussions about U.S. agricultural emissions, experts say.

The methane gas cattle and sheep release during digestion is the number one contributor to agricultural greenhouse gas worldwide, but crop-based emissions should not be ignored, Schechinger noted.

“What sets nitrous oxide apart is both its potency and its relative invisibility in the climate emissions conversation,” said Michael Roberts, the senior program officer for Midwest climate and energy at the McKnight Foundation, a Minnesota-based philanthropic organization that supports environmental and climate initiatives across the Midwest.

In September, the McKnight Foundation published a report examining the role of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer in driving nitrous oxide emissions.

That report emphasized the importance of tackling nitrous oxide emissions through both emissions-conscious field management and technological improvements to fertilizer production.

“Over the last 15 years, there’s been a lot of conversation around the potential for agriculture, performed correctly, to be a carbon sink,” said Roberts. “But we can’t really look to agriculture to draw down carbon until we actually tackle the emissions issue.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,