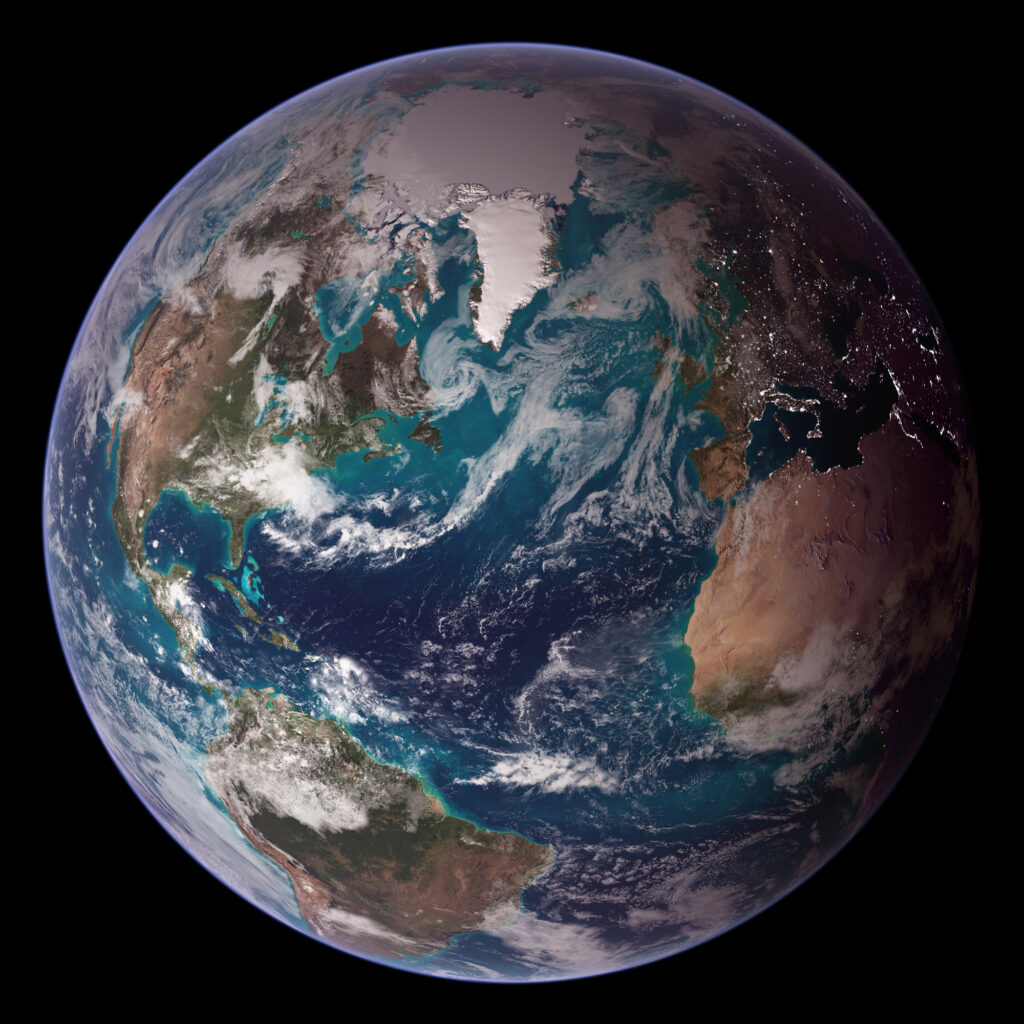

Pictures of Earth from outer space often show the planet as a gaudy quilt. Shimmering aquamarine water covers more than 70 percent of its surface and those hues often seem to signify life against the vast darkness of the universe. But new research analyzing satellite images of the planet over a span of more than 20 years found that one shade of ocean green, representing chlorophyll produced by phytoplankton, is fading.

The fading ocean green, a sign of phytoplankton decline, is a red flag for key ocean systems that sustain food chains and regulate the climate. Phytoplankton, microscopic organisms that have been creating a breathable atmosphere for the planet for more than 2 billion years, are under threat.

The decline in phytoplankton, or even significant shifts in their populations, threaten ecosystems and hundreds of species, from sea turtles and birds to giant marine mammals. Coastal and nearshore fisheries on nearly every continent, which are a crucial food source for an estimated 3 billion people, are also at risk.

To this day, they produce oxygen needed by nearly all other life and regulate the climate by removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in ocean-bottom sediments.

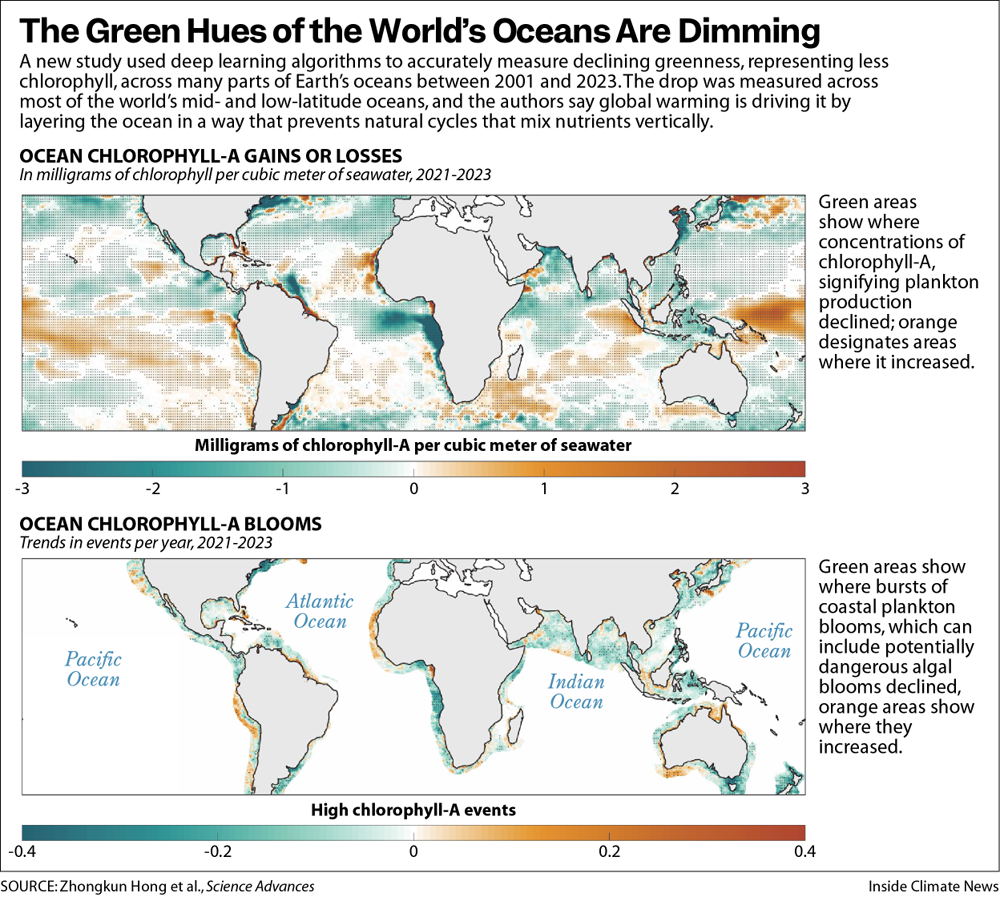

Iestyn Woolway, an ocean researcher at Bangor University in Wales and study co-author, said via email that the research reveals a long-term decline of ocean greenness and phytoplankton bloom frequency across low- and mid-latitude oceans between 2001 and 2023. The scale and consistency of the decline were especially concerning, he added.

It’s a “clear sign” that global warming is already weakening the ocean’s biological carbon pump, one of Earth’s fundamental life-support systems, he said. “A less green ocean not only affects marine food webs but also weakens the ocean’s ability to absorb carbon dioxide—a key buffer against climate change.” Biological carbon pumps cycle carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into deep ocean sediments, where it doesn’t affect the climate.

With the changes visible across vast swaths of ocean and intensifying in coastal zones, the findings suggest “that we’re not just seeing natural variability but a systemic shift,” Woolway said.

The oceans cover 71 percent of the planet’s surface, and they have absorbed about 93 percent of the heat trapped in the atmosphere by greenhouse gases during the fossil-powered industrial era. As the ocean’s surfaces heat up, the water becomes lighter and more buoyant, forming a stable layer that resists mixing with the colder, denser water below. This stratification blocks nutrient-rich, cooler deep water from reaching the surface and starving the phytoplankton that give oceans their greenish tint.

“What worries me most is that these changes are largely invisible to the public,” Woolway said. “Unlike melting glaciers or extreme weather, declining ocean productivity is subtle, slow-moving, and hard to visualize — but it’s no less critical.”

Lead author Di Long, a professor in the Department of Hydraulic Engineering at Tsinghua University in Beijing, said the study results exceeded the team’s expectations. The initial goal was to fill “massive satellite data gaps” to accurately depict changes in ocean greenness over time.

But in the end, he said, they were able to effectively quantify the changes and detect the “surprising downward trend” of greenness, especially in coastal regions, he said.

The unexpected drop in the number of algal blooms is also a significant finding, he said, because some previous research suggested that global warming would “lead to more harmful algal blooms, whereas our results indicate an overall decrease in such blooms.”

More studies are needed to classify algal blooms by species, since some produce toxins that are harmful to marine species and potentially to people, he said. “The worst-case scenario would be a decline in beneficial algal blooms accompanied by an increase in harmful ones.”

The new study is a step in that direction, said Malin Ödalen, an ocean and climate modeler with the Germany-based Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, who did not contribute to the new study.

The more comprehensive data fills in information gaps to show “that what we thought might be an increase in ocean productivity could in fact be a decline,” Ödalen said via email. “Phytoplankton are living close to their thermal range, and that’s why higher sea-surface temperatures can be bad for them—they’re already at the limit of what they can take.”

The new research expands scientific understanding of how global warming affects the biological ocean carbon pump with a detailed daily record of ocean greenness that fills in previous gaps, especially in coastal regions, she said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowWoolway, the co-author from Bangor University, said the new study integrated satellite observations with data from hundreds of automated floats that sample ocean chemistry at different depths. Deep learning algorithms helped fill in data gaps, for example, in areas covered by clouds and revealed the long-term decline in phytoplankton production, he added.

Climate scientist Michael Mann, director of the Penn Center for Science, Sustainability and the Media at the University of Pennsylvania and a co-author of the new study, said via email that he wanted to contribute to examining how it relates to his prior research on ocean stratification.

The research team used sophisticated AI tools to analyze and organize the massive amounts of data from satellites and direct ocean measurements to identify long-term trends across broad geographic areas, Mann said.

Other recent research, including a 2023 study in Nature, has suggested that parts of the world’s oceans have become greener, suggesting greater phytoplankton production, during time periods overlapping with the new study.

Mann said the new research found that declines in phytoplankton production at most latitudes are greater than the increases, adding that the previous assessment “gets the wrong answer because it relies exclusively on one source of satellite data.”

He said the combination of satellite and direct ocean sampling data, analyzed with machine learning methods, is the key advance in this study.

“I’m confident that our result is correct,” he said, “because it’s what we suspected must be happening, given the previously documented substantial increases in global ocean stratification in recent decades.”

Even if humanity manages to stop producing climate pollution and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels stop rising, “sub-surface warming will continue for some time,” he said. That would intensify stratification and further suppress phytoplankton production. That, he said, “is a reminder of the long legacy of some of the consequences of fossil fuel burning and planetary warming.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,