SATIPO, Peru—Dry leaves rustled beneath the hem of her terracotta-tinted dress as Micaela Huaman Fernandez knelt on the forest floor. Leaning in toward the base of a moss-covered palo santo tree, she pointed to a flicker of tiny golden insects fluttering in and out of view.

“Shinkenka,” she murmured softly, watching them vanish through a small waxen tunnel fused to the tree trunk—a narrow passageway to their hidden nest.

It was the name her Asháninka ancestors had given the insects long ago—a stingless bee species revered as sacred by the Indigenous people for the distinctive honey it produces. For generations, it had been offered as a cure for wounds, cataracts, fevers, even infertility. In Spanish, Huaman added, some beekeepers like herself also call them angelitas—or “little angels.”

“They’re so sweet and gentle,” she said.

True to their name, stingless bees don’t sting—they can’t. Unlike the honeybees brought to the Americas by European colonizers to produce wax for candle making in the 1800s—the ones some Asháninka call “killer bees”—these native species don’t have functional stingers.

For at least 80 million years, since the time of the dinosaurs, these bees have helped sustain the world’s tropical forests, pollinating plants and trees that anchor entire ecosystems. More than 600 of the stingless species, also known as meliponines, have been identified by scientists around the globe, including at least 175 in Peru. Yet they have long flown under the public’s radar.

“Most people didn’t even know these bees existed,” said Rosa Vásquez Espinoza, a chemical biologist and National Geographic explorer from Peru, who founded Amazon Research International, a nonprofit dedicated to conserving Amazonian biodiversity, ecosystems, and Indigenous knowledge.

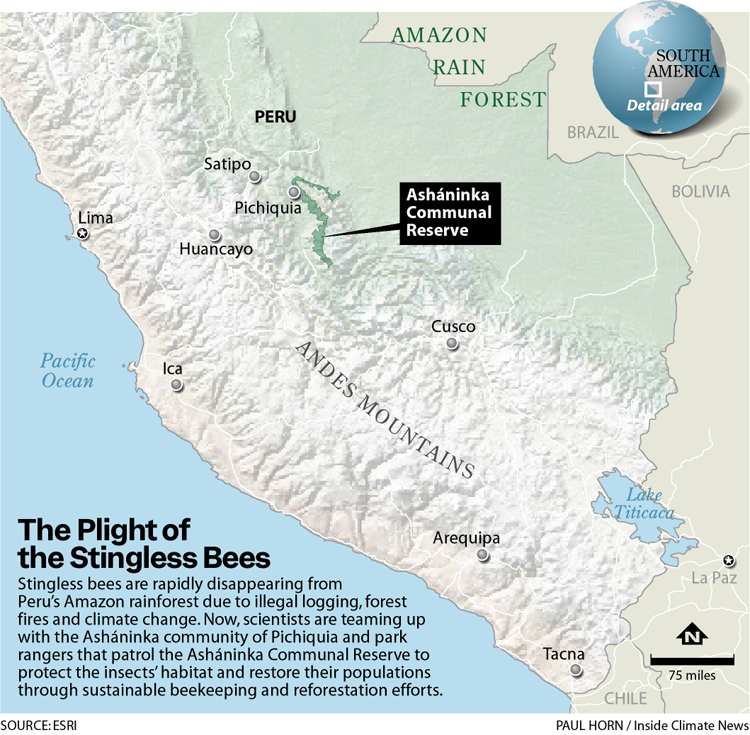

Outside of the forests they inhabit, “they’ve been invisible,” Espinoza said, observing the “little angels” with Huaman inside the Asháninka Communal Reserve. The nationally protected area is co-managed by Indigenous peoples and spans some 700 square miles of tropical forest, mountains and rivers in the central Peruvian Amazon.

In recent years, that lack of recognition, Espinoza said, has come at a cost. The tiny pollinators have been vanishing rapidly, and mostly without notice, in Peru.

Until now.

Overlooked Pollinators

On Tuesday, the local government of Satipo—the largest and easternmost province in Peru’s department of Junín—declared Amazonian stingless bees subjects of legal rights within the Avireri-Vraem Biosphere Reserve. This large protected area in central Peru, established by UNESCO in 2021, includes nearly 16,000 square miles of diverse ecosystems, from the Amazon rainforest to the Andes mountains. The Asháninka Communal Reserve is also located here.

Under local law, meliponines now have legal rights to exist, regenerate and maintain healthy populations within their natural environment, free of harm from invasive species or human activity. They also have the right to have their habitat restored in cases where it has been destroyed and be defended when their rights are violated.

This law marks one of the latest milestones in the rapidly growing global rights of nature movement, which aims to grant legal standing to species and ecosystems, such as rivers, mountains and forests.

“It is the first time that any legal entity in the world recognizes the rights of an insect,” said Espinoza, who has spent the last few years advocating for stingless bee rights, along with the Earth Law Center, a U.S.-based nonprofit that advances Rights of Nature policies, and Asháninka leaders.

The new Satipo Declaration of Rights of the Amazonian Stingless Bees builds on a national law passed last year that the group also advocated for, which, for the first time, granted protections to the native bees and acknowledged them as species of economic importance. Until then, only European honeybees, also known as Apis mellifera, were safeguarded by Peruvian law.

“Their conservation ensures the genetic diversity of wild species, a biological resource of enormous value for climate change adaptation and resilience programs,” said Verónica Cañedo, an entomologist employed by Peru’s Ministry of Environment. “These bees also support ecological processes vital to forest regeneration and ecosystem preservation, which contributes to environmental health and the well-being of the human communities that depend on them,” she said.

Now, with the latest recognition of stingless bee rights, Espinoza said, there will be even more impetus to protect them.

It will be easier to take legal action against those engaging in any behavior or activity that harms the insects, like using pesticides or cultivating non-native honeybees in protected areas, or deforesting critical habitat. But, punitive action is not the only goal, she said.

The declaration acknowledges the deep cultural connections Indigenous peoples have with the species and their invaluable role in helping conserve them and the forests they live in.

“The rights of stingless bees of the Peruvian Amazon are intrinsic and inseparably connected with the human rights and welfare of present and future generations,” it says.

Hopefully, Espinoza said, this declaration will incentivize the designation of special funds to support local communities in restoring the native insects through sustainable stingless beekeeping and reforestation efforts, as well as ongoing scientific research.

From the Asháninka living in higher-altitude mountainous areas of the Amazon jungle to the Kukama-Kukamiria communities settled closer to the Amazon River in the northeastern part of the country, Indigenous peoples have long relied on meliponines to produce both food and medicine. More than 75 percent of agricultural crops’ are supported by native bees, which help boost fruit and seed productivity.

“Without them we would not live. They pollinate the plants we eat,” said Huaman, a 31-year old mother of twin boys from Marontoari, an Asháninka community located on the western side of the Asháninka reserve.

Espinoza first learned about rights of nature laws several years ago through marine biologist Callie Veelenturf, from Massachusetts, who founded a sea turtle conservation nonprofit, The Leatherback Project. Veelenturf helped draft and advocate for a national rights of nature law in Panama, which was passed in 2022, and a subsequent law passed a year later that granted specific legal rights to sea turtles. The country’s Indigenous Guna people believe sea turtles carry the spirits of their deceased relatives.

That law states that both the animals and their habitats have rights to remain free from harm caused by plastic pollution, discarded fishing gear and the escalating effects of climate change. It also empowers Panamanian citizens to take legal action to defend those rights.

Immediately, the concept resonated with Espinoza, who descends from a long matrilineal line of Indigenous Quechua people from the Andes mountains and has deep familial ties to the Amazon, where many Indigenous peoples also have strong spiritual relationships with nature.

Similar to the Guna’s bond with sea turtles, the Asháninka share a sacred familial connection to stingless bees.

“Bees are part of the family,” said César Ramos, president of EcoAsháninka, an organization that represents around 8,000 people from 25 Indigenous Asháninka, Machiguenga and Kakinte communities based in the Asháninka reserve. “They are ancestors,” he said.

Earlier this summer, Espinoza led a two-week scientific expedition inside the protected area, as well as a nearby village, called Pichiquia, where around 800 Asháninka people live along the Ene River. She was joined by several Peruvian officials, including Cañedo and a local government representative from Satipo, as well as a group of other Peruvian and international scientists, Asháninka leaders and park rangers charged with patrolling the reserve.

Their plan was to track the elusive bees, chart their threatened habitats and train local community members to help revive their dwindling populations. Along the way, they would also facilitate workshops on what it would mean to recognize and defend the insects as rights-bearing beings.

That journey, Espinoza said, proved vital in paving the way for the recent adoption of the new declaration and preparing community members to soon take the lead in implementing it with the support of local government.

For the first time, she said, it put Peru’s stingless bees in the spotlight.

Defending Stingless Bee Rights

On one of the first days of the expedition, Espinoza and the rest of the expedition filed into Pichiquia’s run-down primary school, decorated with faded alphabet posters and handwriting charts.

The classroom’s green and blue, child-sized, paint-chipped chairs were quickly filled, mostly by local men. A few women lingered outside, peering through the windows or hovering in the doorway, until Espinoza smiled and motioned for them to join. Near the front sat two of her mentees training to become park rangers inside the Asháninka reserve: Maida Quispe Roca, 27, from an Indigenous Quechua community in Peru’s department of Ayacucho, and Katy Tatiana Canay Torres, a 22-year-old Asháninka student studying aquaculture at a local technology institute in Satipo.

Much like the bees, Espinoza said, Indigenous peoples—especially Indigenous women—have been overlooked or ignored in scientific spaces. She wanted to shift that trend.

“We’ve missed the voices of the local people,” she said. Without centering them in research, she warned, “We’re just putting on a Band-Aid.”

In September, her commitment was recognized by UNESCO, which granted her the Al Fozan International Prize. The award, given every two years to five scientists worldwide, celebrates leaders advancing science and technology aimed at solving urgent global challenges.

In her acceptance speech, she said, “The Al Fozan Prize is not just a recognition of my work. It is a recognition of all of those who have been excluded from science for too long.” Working with the Asháninka communities on the declaration of legal rights for the stingless bees, she said, was a way to change this.

Inside the classroom, Javier Ruiz, an environmental lawyer from Mexico who works for the Earth Law Center, welcomed the group to the morning workshop on stingless bee rights. Their input, he said, was essential for creating a declaration that would protect the pollinators. “Why?” he asked. “Because you live with these native bees. Because you know the threats the bees are facing.”

He then held up a stack of laminated placards printed in both Spanish and the Asháninka language, each naming a potential threat. It was important to identify the risks stingless bees faced in order to conserve them, he said. He invited volunteers to step forward and choose the ones they believed most urgent, and fix them to the classroom’s whiteboard with tape.

At the top of the list, one person posted “cambio climatico,” or climate change. Another posted “deforestación” below.

Rising temperatures were forcing some of the bees to move toward areas at higher altitudes with cooler climates in this central part of the Amazon, said César Delgado, a Peruvian entomologist of Indigenous Kukama-Kukamiria origin, who works for theInstitute of Investigation of the Peruvian Amazon, a government research body. A hotter, drier climate was also spurring droughts and severe lightning storms, both of which, he said, fueled more frequent and widespread wildfires.

Last year, the Peruvian Amazon lost more than 100,000 acres of forest to fires, according to the Monitoring of the Andes Amazon Program, which uses satellite technologies to detect deforestation and fires in real time. That was more than double the amount of Amazon forest Peru lost to fires in 2023.

Meanwhile, more than half the bees’ habitat in the UNESCO biosphere is jeopardized by illegal loggers, according to a recent study Espinoza co-authored and published in the Journal of Ecology and Environment with Delgado and Richar Demetrio, an Asháninka park ranger, scientist and stingless beekeeper.

“The rights of stingless bees of the Peruvian Amazon are intrinsic and inseparably connected with the human rights and welfare of present and future generations.”

— The Declaration of Rights of the Amazonian Stingless Bees

Drug traffickers also clear large areas of forest within the region to plant illicit coca crops, grown to supply a rising international demand for cocaine. Nearly half of Peru’s illegal drug trade stems from this part of the country, according to a recent report by the country’s National Commission for Development and Life without Drugs, a government agency, which leads the country’s anti-drug policy.

Several years ago, a group of traffickers attempted to invade the Asháninka reserve, but were pushed out by Indigenous leaders. Since then, they have managed to keep them at bay, but Ramos said, “we are on constant alert.”

Soon, the whiteboard filled with additional threats, including pesticides and competition with invasive species. The European or African honeybees, Delgado said, appeared to be outfeeding native bees in some places. Another risk, workshop participants noted, was the loss of traditional knowledge about local plants, animals and trees. It’s hard to know what is being lost if there’s no knowledge left of what currently exists, or existed before, Delgado explained.

Many of the threats listed were not only jeopardizing stingless bees in Peru, but pollinators around the globe. Honeybees and butterflies, for instance, have experienced drastic declines in recent decades due to pesticides and habitat loss.

“We are facing one of the most, if not the most significant, extinctions that we will see in our lifetimes, of insects as a whole, including our pollinators,” said Kathryn Naherny, an entomologist and doctoral student at University of Colorado’s Boulder Bee Lab, who joined the expedition. As part of her fieldwork for her dissertation, she is working with Espinoza and Delgado to collect samples of stingless bee species and their honey across the Peruvian Amazon.

To counter these threats, Bastián Núñez—another Earth Law Center lawyer from Chile—made a proposal to his audience: What if bees had the right to live in a healthy environment with access to plants and trees that helped combat climate change? What if the insects had the right to repopulate and grow their populations? What if they were entitled to being restored with the support of people like those present on this day in the classroom? Or protected from pollutants or interference from invasive pests?

In other parts of Peru, nature had been granted similar rights, he said.

Last year, the Marañón River—a vital Amazonian tributary in Peru—was recognized by the Superior Court of Justice of Loreto as a living entity with inherent rights to exist, flow freely and remain unpolluted. The rights were granted after a group of Indigenous Kukama-Kukamiria women filed a lawsuit against the Peruvian government and the state oil company, Petroperú, over recurring oil spills that desecrated the river they consider central to their cultural and spiritual identity.

In April, a local law was passed in the city of Puno in Southeastern Peru that recognizes Lake Titicaca—the world’s highest navigable lake, which is considered sacred by the Indigenous Aymara people—as a subject of legal rights and obligates regional authorities to protect it from mounting pollution caused by sewage and solid waste from nearby cities. Over the last few years, Núñez said, the Earth Law Center and Espinoza’s team at Amazon Research International had been drafting a declaration to reflect the rights of stingless bees in collaboration with Asháninka leaders. They planned to propose it to the local municipality of Satipo after the expedition to see if it could become local enforceable law. But it was important that the entire community was in agreement.

“Would they support such rights?” he asked. A chorus of voices rose in reply — “Sí!” — their “yes” echoing through the classroom.

“We are facing one of the most, if not the most significant, extinctions that we will see in our lifetimes, of insects as a whole, including our pollinators.”

— Kathryn Naherny, University of Colorado’s Boulder Bee Lab

If passed, he explained, the document would serve as a powerful tool for the community to pressure authorities and advocate for the necessary resources to protect both the bees and their habitat. “It shows that you are organized and that you speak the language of law, because you, all of you here, are defenders of nature,” he said. “It’s very difficult for an authority to go against you if you use legal, professional, technical language.”

In the meantime, Espinoza stressed, the developing words on paper had to be matched with action. Conserving the bees would require concerted efforts on the community’s part that would not only benefit the insects, but them as well.

“Training is needed on how to improve bee health, how to care for them, how to increase the population and also how to generate a sustainable economy, because conservation has to go hand in hand with the economy,” she said.

A Special Kind of Honey

In 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Espinoza was finishing her Ph.D. in chemical biology at the University of Michigan, but worried how communities back home in Peru were coping. She called Delgado, who was based in the Amazon at the time, to ask what he was seeing. Espinoza had met the renowned entomologist years earlier when she was a teenager during one of her family’s regular trips to the Amazon from their home in Lima, where she was raised. She had followed his research on pollinators since then.

He told her many communities were using stingless bee honey as one of their primary treatments for severe respiratory infections. This fascinated her, she said. Together, the two scientists began analyzing honey samples collected from local people selling the product. The honey they examined came from two different meliponine species: the Melipona eburnea and the Tetragonisca angustula, which the Asháninka call “shinkenka,” or “angelitas.” What they found, Delgado said, was remarkable.

“This is not just any honey,” he said. “It is special honey.”

Stingless bee honey is more watery and acidic than that produced by European honeybees. It also has a wide range of flavors, said Naherny, from the Boulder Bee Lab. “Some of them taste like the most tart teriyaki sauce you can imagine,” she said. Others are smoky and citrusy, resembling a “lemon peel tea,” she said. “The sweetest honey is like pure ambrosia nectar.”

But it is not just their flavors that make them special.

According to Espinoza’s and Delgado’s research findings, published in 2023 in the journal Food and Humanity, stingless bee honey contained molecules with anticancer, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory and even antiviral properties—traces, which Espinoza said, were likely derived from the bees’ intimate connection to the medicinal plants and microbes of the Amazon rainforest.

Since then, Espinoza said, she and Delgado have been helping communities use this information to promote stingless beekeeping and the sale of stingless bee honey as a scientifically backed, highly medicinal product. As a result, she said, the prices for this special honey had risen significantly in the last several years throughout the Peruvian Amazon. A half liter of honey that used to sell for around $3 now goes for about $20, she said.

“Interest in stingless bee honey is growing every month,” Delgado said.

Here, in Peru’s province of Satipo, stingless beekeeping posed an intriguing prospect for communities like Pichiquia, which the EcoAsháninka president, Ramos, said, lacked government support. “The state is not providing services,” he said. “Pichiquia has been abandoned.”

Like many other communities in the region, it is in grave need of basics: safe drinking water, electricity, school supplies and sometimes food. Many people in the area survive in large part from subsistence hunting, fishing and small-scale agriculture. With few economic alternatives, Delgado said some have been pressured into renting their land to drug traffickers.

“These native communities, primarily the Asháninka ones, where drug trafficking is quite prevalent, have long been decimated, or cut off from parts of their territory.” Selling honey, he said, could provide an opportunity to reclaim some of what they’ve lost, and help them defend their territory in the future.

This incentive was important. “If communities are benefiting, they are going to conserve more,” he said.

A day after the group convened inside the classroom to discuss stingless bee rights, they gathered again, this time in the center of Pichiquia’s earthen plaza, shaded only by a few scattered trees. During this morning’s workshop they would learn how to support the bees’ rights to maintain healthy populations.

They gathered in a loose semicircle around two wooden bee boxes placed on stilts raised a few feet off the ground. Leading the workshop were Delgado, Espinoza and Huaman, who stood shoulder to shoulder preparing to open the boxes as the curious onlookers leaned in.

“Sustainable beekeeping is one of the best ways to help their populations recover,” Espinoza told them.

It was a way to monitor the health of the colonies and protect them from threats they might otherwise face in their natural habitat. Their colonies could also be split and multiplied, she said.

Sustainable Stingless Beekeeping

Meliponiculture, or the practice of stingless beekeeping, has long been a customary practice amongst Indigenous peoples in the Amazon, who have used both the native bees’ honey and pollen for food and medicine.

They’ve also used a resinous substance produced by the bees called propolis—a mixture of plant resins and wax the insects use to build and defend their nests—to make candles and to prepare arrows for hunting and fishing, according to a study on traditional stingless bee knowledge in Asháninka communities, co-published by Espinoza, Delgado and Demetrio earlier this year in the journal Ethnobiology and Conservation.

But harvesting these products hasn’t always been done sustainably, said Demetrio.

In recent years, he had started training fellow community members how to raise the bees and multiply their hives to boost their populations. One of those people was Huaman.

Last year she participated in a day-long meliponiculture workshop, which she said immediately sparked her interest. Before that, she said she had considered herself too shy or quiet to speak publicly or lead any sort of project. But, the bees had inspired her to try something new.

“I feel very excited and happy working with the bees,” she said. “As a woman it has strengthened me.” It’s also given her a new sense of purpose, she said. One that she hopes to pass on to others like her.

In her ochre-colored kushma—a traditional type of dress—embroidered with designs of bees, Huaman demonstrated to the young park rangers in training, Torres and Roca, how to open the box and inspect the hive for pests or disease. In stark contrast to the more well-known hexagonal combs made by European or African honeybees, the dark gray hive of the Melipona eburnea was shaped like a soccer ball, riddled with craters and distinct grape-sized honeypots.

Historically, she explained, some people would extract the honey by squeezing the honeypots, destroying parts of the hive in the process.

To preserve the hive required a far more delicate process—one that demanded patience, she said. Then, she demonstrated how to extract honey from the bees’ tiny honeypots with a plastic syringe.

In the last year, Huaman has started caring for four stingless bee hives she keeps near her home in Marontoari. She sells medicinal tinctures made from the honey her bees produce and shares her meliponiculture knowledge locally and abroad. Last year, Espinoza’s organization, Amazon Research International, helped send her to the United Nations biodiversity COP16 in Cali, Colombia, to speak about stingless beekeeping.

But, on this trip, she wanted to learn more, especially how to find and remove a wild hive from the forest, which traditionally, she said, had been reserved for men. A few days later, she would have her chance.

Mapping Stingless Bees

From Pichiquia, the expedition trekked into the Asháninka Communal Reserve, setting up camp at a ranger control post managed by Peru’s National Service of Natural Protected Areas (SERNANP). The journey—about four hours on foot—wound through steep mountain paths cut through dense tropical forest and across fast-moving rivers. Along the way, they passed through small family garden plots of yuca, cacao and bananas.

While in the reserve, the team began to search for the bees with the help of park rangers, like Demetrio, who has been patrolling the reserve over the last 10 years.

Stingless bee nests are typically hidden. But, as a child Demetrio’s father had shown him how to track them by attuning his ear to the insects’ low, distinct buzz amid the rainforest’s orchestra of other sounds and following them to their source. He was also well adept at spotting the entrances to their nests, each of which was distinct, almost like a fingerprint, he said. Some appear as long straw-like tubes. Others are wide and spiky. Some are extremely camouflaged and hardly visible. All of them, though, lead to intricate homes, usually hidden deep within the hollows of old tree trunks or tangled roots, sometimes in termite nests or other mounds of soil.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowIn recent years, they had become even harder to find as their populations had declined, Espinoza said. She had heard from various sources in the region that stingless bee nests once were easily found within thirty minutes of walking in the forest. Now, she said, “You can easily go four hours, five hours, sometimes not even finding one in a single day.”

But finding those that remained was essential to the bees’ survival.

In recent years, Espinoza and Demetrio had started documenting the locations of wild nests throughout the biosphere. They were collecting critical data, they said, that would be used to produce some of the first maps of stingless bee territory, which they hoped would soon be used to defend the bees legal rights to exist and thrive in a healthy environment.

“Recognizing stingless bee habitats within a Rights of Nature framework would create legal accountability for habitat destruction,” the study they had co-published in the Journal of Ecology and Environment this past summer stated.

One morning, Espinoza headed out from camp with a small group from the expedition team to find some ground-dwelling stingless bees a park ranger had spotted earlier. The Asháninka called them “devil bees,” Demetrio said. These insects didn’t feed on plants, like other stingless species. They fed on the carcasses of dead animals and were considered toxic, he said. Espinoza was thrilled.

“We’ve been looking for toxic honey for years.” she said. “But no one ever wants to show us where it is, so this is fortuitous.”

The team took turns using a shovel, axe and their hands to uncover a basketball-sized nest buried several feet deep underground.

“It’s like you’re unearthing a fossil,” Naherny said. “You want to preserve the structure and reduce dirt getting into the nest.”

As the nest finally came into view, Espinoza raised her iPad, snapping photos while bees began to swirl around her face and hair. Stingless though they were, they could still bite—and hard. She’d learned that the painful way before. Carefully, she stepped back as Naherny moved in with a slim plastic aspirator she called a “bug tube” pressed between her lips. Then she began gently sucking a few bees inside that would be preserved in test tubes and sampled in a lab later on. It was possible that the species had not yet been scientifically described, she said.

Espinoza handed Roca—the young Quechua park ranger in training—a cell-phone sized GPS device, showing her how to log the coordinates of the nest. With these data points, she explained, she planned to advocate for the creation of “bee-friendly corridors.” These would be continuous stretches of protected forest where stingless bees could exercise their rights to live and move freely in a healthy connected ecosystem.

Reforestation was also central to that plan. By planting native trees and flowering plants in burned or degraded areas, Espinoza intended to restore the bees’ habitat. The bees, in turn, would help accelerate the forest’s recovery through pollination, she said.

Later that afternoon, they gathered near another nest Demetrio had spotted months before and had been watching closely since.

It was the little angels’ hidden nest within the moss-covered palo santo tree.

As Huaman and Espinoza peered into the angelitas’ delicate entrance, Delgado explained to the rest of the expedition team that in some places people felled entire trees to hack into wild nests and harvest the bees’ honey. But that wasn’t sustainable, nor was it necessary, he said.

The nest could be removed without causing the tree harm. A better practice, Delgado explained, was to cut a small opening in the trunk to carefully extract the wild nest.

To demonstrate this, EcoAsháninka president César Ramos stepped forward, his ankle-length cotton robe brushing the forest floor, a crown of feathers atop his head, denoting his authority. Huaman stepped back to give him space as he gripped the handle of a growling chainsaw.

The sharp whir of the blade broke through the forest’s quiet as Ramos pressed it carefully against the trunk of the palo santo tree, carving a clean rectangular frame around the spot where Delgado had estimated the nest resided inside.

Huaman watched closely. “Someday I want to do that,” she murmured, as fine wood chips sprayed through the air.

When the final piece of bark came free, the heart of the nest was revealed, a delicate architecture of wax and resin tucked inside the hollow. Delgado crouched near the opening, showing the group how to gently lift the nest and settle it into the bee box, where the bees could continue to thrive and repopulate, exercising their right to regenerate.

Then Delgado sealed the tree’s wound with the same piece of wood that had been removed and placed the box flush against the trunk. One of the park rangers sprinkled ash around its base to deter pests from entering. The tree would recover, Espinoza said. And so would the colony.

To help lure the bees that had scattered in the commotion into their new home, she squeezed a few drops of their honey from a syringe around the entrance of the bee box.

A few days later, when she and Huaman returned, they saw the golden bees flutter around the palo santo tree again, this time flitting in and out of the box, as well as the cuts that had been sawed into the tree. The bees had started to rebuild in both places. The hive had effectively doubled.

Soon, the box would be transferred to a stretch of forest scarred by fire so the bees could help pollinate and restore the area. For Espinoza, the process was an encouraging glimpse of what the new declaration of stingless bee rights could help grow: a shared effort between scientists, government and local communities to not only defend nature, but help it heal.

This reporting was supported by the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Women Deliver Reporting Grants.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,