Two years ago, Ignacio, a construction worker in Houston, began having frequent headaches and fatigue. Then 40, he initially didn’t go to a doctor because he was uninsured. His wife found a clinic that would see him for free.

He was diagnosed with high blood pressure and high cholesterol and sent home. A few hours later, someone from the clinic called, asking Ignacio to return immediately. When he failed to show up, the clinic employee called again. He needed to go to urgent care because his heart could fail while he was asleep, they told him.

Ignacio, who is undocumented and asked that his last name not be used, was diagnosed with Stage 5 kidney disease and now undergoes dialysis three times a week, for four hours at a time.

An underappreciated threat—heat—may be at the root of Ignacio’s condition. Indeed, some researchers have called chronic kidney disease the first chronic illness directly linked to climate change. While no clinical test exists to determine the precise cause of the ailment known as CKD, a growing body of evidence shows that working in hot weather slowly damages the kidneys. Ignacio has worked in construction in Texas, one of the hottest states, for more than 10 years.

CKD has upended Ignacio’s life and mental health. At first, he thought he was going to die and worried what his family would do without him; his youngest daughter was four when he was diagnosed. He used to work 70 to 80 hours a week, but now can work only 40.

“It’s like now I only have half of my life,” Ignacio said. “Your life now depends on this [dialysis] machine.”

Researchers are still unraveling all the ways extreme heat affects the human body. Early in this century, researchers in warmer parts of the world—Central America, South Asia—began noticing a spike in kidney disease among younger, otherwise healthy people. Many looked like Ignacio: they hadn’t previously been diagnosed with diabetes or hypertension and their occupations exposed them to heat day in and out.

Although they acknowledge the surge in CKD could have multiple causes, health experts nevertheless have concluded that there is a common denominator: hotter temperatures.

A diagnosis of Stage 4 or Stage 5 kidney disease can lower a person’s life expectancy by 15 to 20 years, condemn them to lifelong dialysis and disrupt their immune, endocrine and circulatory systems. Nearly one out of four or five chronic kidney disease patients experiences a major depressive disorder. Mental health problems are so common among dialysis users that Medicare guidelines require patients to be screened for depression after 90 days in treatment and then at least once a year. In June, a review paper found that the suicide rate among dialysis patients is at least double the rate of the general population.

About This Story

This is the third in an occasional series of stories exploring the effects of rising temperatures across Texas. The project is a collaboration between Inside Climate News, the San Antonio Express-News and Public Health Watch.

Georgia Tuma, a social worker with the South Texas Renal Care Group in San Antonio, said that dialysis can be as disruptive as chemotherapy to some patients. “It is a big change, and it is scary,” she said. “You lose some independence. You have to rely on people. Your time is not your time anymore.”

Unlike chemotherapy, dialysis can become normalized. Support for the patient can fall off. “I wish there was a lot more community support and family involvement,” Tuma said.

Occupational Heat Exposure and Kidney Disease

The kidneys are among the organs most vulnerable to heat. An analysis of more than 20 million emergency room visits in almost every U.S. county over a decade found that extreme-heat days were 30 percent likelier to have ER visits for renal disease, second only to a 66 percent increase for heat illnesses such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion.

Workers routinely exposed to heat—in construction, landscaping and agriculture, for example—are at greatest risk. The International Labour Organization estimates that 26.2 million people worldwide are living with CKD attributable to work-related heat stress.

When Bethany Boggess Alcauter conducted a pilot study of heat-related kidney disease among construction workers in Texas, she was struck by the findings. The study, funded by the Southwest Center for Occupational and Environmental Health at UT Health Houston, followed 16 workers for a couple of days in 2022. One was taken to the emergency room after suffering heat stroke.

“Because the study was so small,” Boggess Alcauter said, “I hadn’t anticipated what should be a very rare event.”

Boggess Alcauter, director of research and public health programs at the nonprofit National Center for Farmworker Health, based in Buda, had previously worked with La Isla Network, a nonprofit research group studying kidney disease among young, heat-exposed agricultural workers in Central America and Asia. She wondered if heat was affecting workers in the United States. About half the workers she studied in Texas had blood in their urine, and some had brown urine—signs of severe dehydration. Boggess Alcauter found evidence of early kidney damage in 12 percent of the workers.

“We know what to do to prevent this kind of thing, and it costs almost no money,” she said. Simple interventions like providing workers with shade, water and frequent breaks can help protect their kidneys.

In heat-related injury reports filed with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, over the past decade, employers said 23 workers in Texas suffered some type of kidney damage. (OSHA only requires the reporting of severe injuries, so this may be an undercount).

In June 2023, a worker began feeling dehydrated while installing solar panels in Houston. He was hospitalized with acute kidney failure and heat exhaustion.

Two months later, two workers in indoor plants in Waco and Dallas were hospitalized for dehydration and kidney damage. In the summer of 2024, two other workers, in San Antonio and Victoria, were hospitalized for dehydration and acute kidney injury. The first worker was checking water meters on the street; the second was pouring concrete for a driveway. On the days of those incidents, the temperature reached 100 degrees in San Antonio and 90 in Victoria.

This past June, Tara Johnson, a UPS driver in Arlington, near Dallas, spent 11 hours in her non-air-conditioned truck as the temperature climbed to 93 degrees. She was delivering a package in an apartment building when a resident noticed she was pale and dizzy and called an ambulance. A doctor confirmed that she was having heat stroke and needed to be hospitalized for acute kidney injury. Johnson was out sick for a month. The second day she was back at work, she suffered heat stroke again. She made it through the day but collapsed as soon as she got home. A doctor again warned her about kidney function. “I am so afraid that I am going to damage my kidneys,” she said.

Despite the obvious risks, there is no federal heat standard for workers, though the Biden administration proposed one that would require employers to provide drinking water, bathroom facilities, shaded break areas and other measures when the wet bulb temperature—an indicator that takes humidity into account—reaches either 80 or 90 degrees Fahrenheit, depending on the form of protection. Hearings on the proposal have been held since June, but its fate is uncertain.

Until 2023, the cities of Austin and Dallas mandated water breaks every four hours for people who worked in the heat. But the Texas Legislature nullified those ordinances as part of a crackdown on local rule.

To protect heat-susceptible workers, La Isla Network has developed preventive measures that center on water, shade and rest. Among sugarcane workers in Central America, mandated breaks, tents, access to purified water with electrolytes and other precautions—have reduced acute kidney injury by 94 percent and increased productivity by 10 percent to 20 percent, according to a 2024 International Labour Organization report.

For three years, Jason Glaser, the CEO of La Isla Network, has tried to promote greater use of those practices in the U.S. This year, the organization was preparing to expand partnerships with U.S. employers when word came that it would lose two-thirds of its federal funding. The cuts were driven by the Trump administration’s Department of Government Efficiency, or DOGE, Glaser wrote in a letter published online. Now, the organization’s efforts in the U.S. are stalled.

“Why do workers in a field in Nicaragua have better protections than a worker in Texas?” Glaser asked in an interview with Public Health Watch.

How Heat Damages Kidneys

When it’s hot outside and the body sweats, the kidneys filter less blood to conserve fluid and prevent dehydration, said Zachary Schlader, a kinesiology professor at Indiana University Bloomington who studies how the thermal environment affects the human body. If the temporary reduction in kidney function reaches a certain level, a person suffers acute kidney injury.

Until 15 years ago, scientists believed a decrease in kidney function wasn’t in itself alarming, Schlader said, because the kidneys would go back to normal after the person cooled down. But studies have since shown that repeated episodes of even mild kidney injury significantly raise the chances of developing chronic kidney disease—the irreversible loss of kidney function.

Climate change has lengthened the hot season in many parts of the U.S., which enhances the risk for workers. Schlader and other researchers found that just a few extra degrees in the wet bulb temperature can heighten the risk of acute kidney injury.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowA study published in 2018 looked at almost 200 agricultural workers in Florida and found that one in three had acute kidney injury at least once a week. A paper published in 2020 found agricultural work nearly doubled the chances of workers suffering the condition. A third, published in 2024, found that 38 percent of construction workers participating in a study in Florida had experienced acute kidney injury while on the job.

Chronic kidney disease is often unnoticeable at first. When a victim starts having symptoms—muscle cramps, nausea or fatigue—it’s often too late.

For his doctoral project, Daniel Smith, a nursing professor at the University at Buffalo who has also worked with La Isla Network, examined the occupational histories of dialysis patients in Atlanta. He found a cohort of patients whose medical histories were similar to that of Ignacio, the Houston construction worker: They had worked in heat-exposed occupations, such as construction; had never had diabetes or hypertension; and developed kidney disease at a relatively young age.

Even some indoor workers, like those employed by restaurants, were at risk, Smith found.

“We know heat is bad and hurts people’s kidneys,” he said. He believes equally stringent protections should be required across industries.

Bring the Solution Home

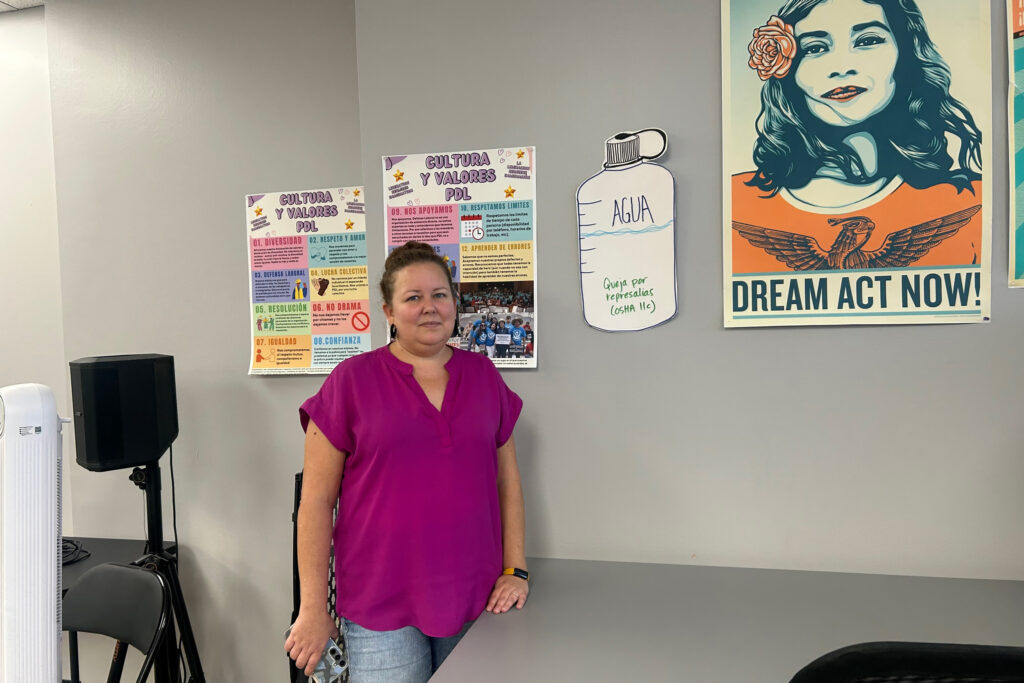

Even if the proposed OSHA heat rule makes it through, more must be done to protect workers from the rapidly warming climate, said Laura Pérez-Boston, organizing director of Workers Defense Action Fund, an advocacy organization in Houston.

Community outreach is a crucial part of the equation, she said.

“A super smart attorney can create the most beautiful policy, but if nobody knows about it, then what good does it do?” Perez-Boston said.

Boggess Alcauter, of the National Center for Farmworker Health, said an economic argument needs to be made to employers wary of federal regulation.

“What’s going to change industry behavior is if we can demonstrate that workers are actually much more productive and can perform much better when they are given breaks and electrolytes and shade,” she said.

The prognosis for Ignacio, the ailing Houston construction worker, is not encouraging.

He spends 12 hours a week in dialysis, a procedure that leaves him physically and emotionally spent. He still works in construction, and now his wife works with him, but their dream of taking a family vacation is out of reach.

He’s hoping for a transplant. He wants his old life back, and credits his three children with keeping him clearheaded.

“My kids have been my driving force to fight depression,” Ignacio said, “because this disease makes you believe things that aren’t true.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,