For centuries, humans have drawn a line between themselves and other species, initially claiming that other animals couldn’t feel pain. Science proved they could. Then the argument shifted: Animals lacked consciousness or the ability to think in complex ways. That, too, fell apart under mounting evidence. Now, a final frontier is language—the belief that only humans possess it.

Even that line is beginning to blur.

With the help of artificial intelligence, robotics and new recording technologies, scientists are edging closer to decoding the vocalizations of elephants, whales and other animals, drawing the world closer to the era of inter-species communication.

At the forefront of this effort is marine biologist David Gruber, whose lifelong fascination with the living world began in childhood, watching the collective intelligence of ants. Gruber, 53, has spent decades trying to understand creatures most people never truly see—protozoa, bioluminescent corals, jellyfish, sharks and now whales.

In 2020, he founded the Cetacean Translation Initiative (Project CETI, or CETI), a nonprofit that listens to and translates the voices of sperm whales. Known as the animal of superlatives, sperm whales are deep-diving, matrilineal giants with the largest brains on Earth. They are also strikingly similar to humans.

CETI’s work is as headline-grabbing as it sounds: Its researchers use artificial intelligence to help understand whale communications and to perhaps one day even hold a conversation. But what makes CETI’s work stand out isn’t just the technology—it’s the philosophy behind it.

Over the years, Gruber has become well known among peers not just for his discoveries, but also for his empathy. He rejects the traditional hierarchy that places humans above other species and believes that scientific research should foster understanding without causing harm or disruption. In practice, he has sought to understand the world from other animals’ perspectives, once building a camera modeled on a shark’s eye to see the world as they do.

Intentions matter, he says. He credits his discovery of a biofluorescent sea turtle in the South Pacific not to luck, but to patience and a respectful presence that allowed the turtle to reveal itself.

“I’ve always felt connected even to the smallest forms of life,” he said in a recent interview. Now, Gruber is seeking to hear the world as sperm whales do. CETI, he explained, is a “deep listening experiment,” meant to shift how humans relate to the natural world—and how they protect it.

In a paper published last week in the journal Ecology Law Quarterly, Gruber and his co-authors argue that CETI’s work could dramatically strengthen legal protections for nonhuman life, including the most powerful safeguard of all: rights.

Gruber is among a growing number of Western scientists supporting the Indigenous-led “rights of nature” movement, which aims to advance the recognition that individual species and ecosystems have inherent value and legal rights.

Their contributions are helping build the already fast-growing movement: Countries including Ecuador, Colombia, New Zealand, Panama, Spain and Uganda already have such laws or court rulings on the books. Western scientists have helped craft some of those laws, grounding them in ecological principles, and have given heft to the movement’s underlying argument that humans are one species in an interdependent web of life.

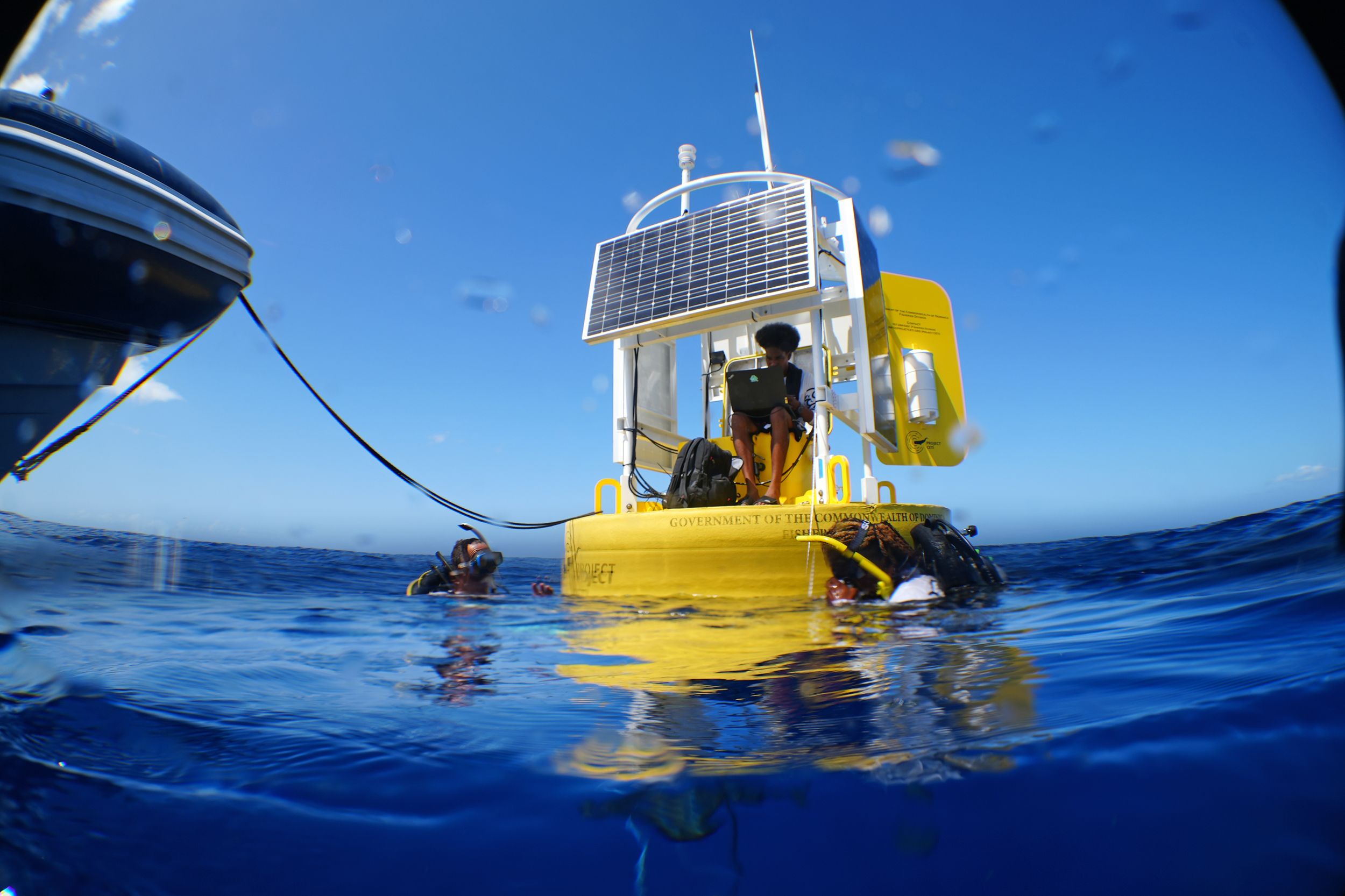

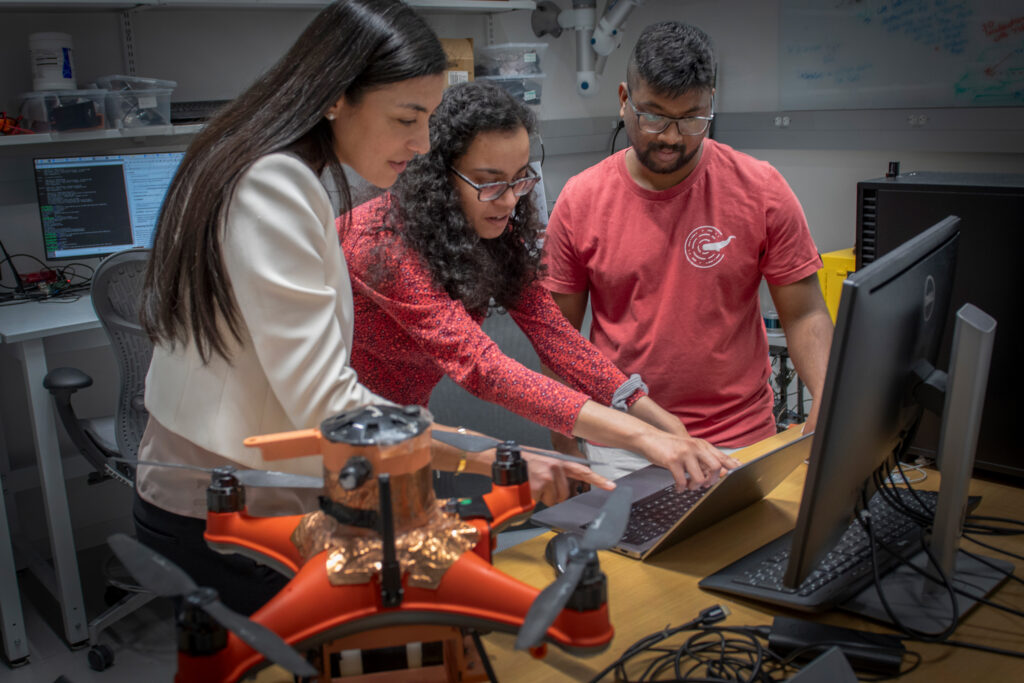

Today, CETI has grown to a team of more than 50 experts in marine biology, artificial intelligence, natural language processing, cryptography, linguistics, robotics, engineering and underwater acoustics.

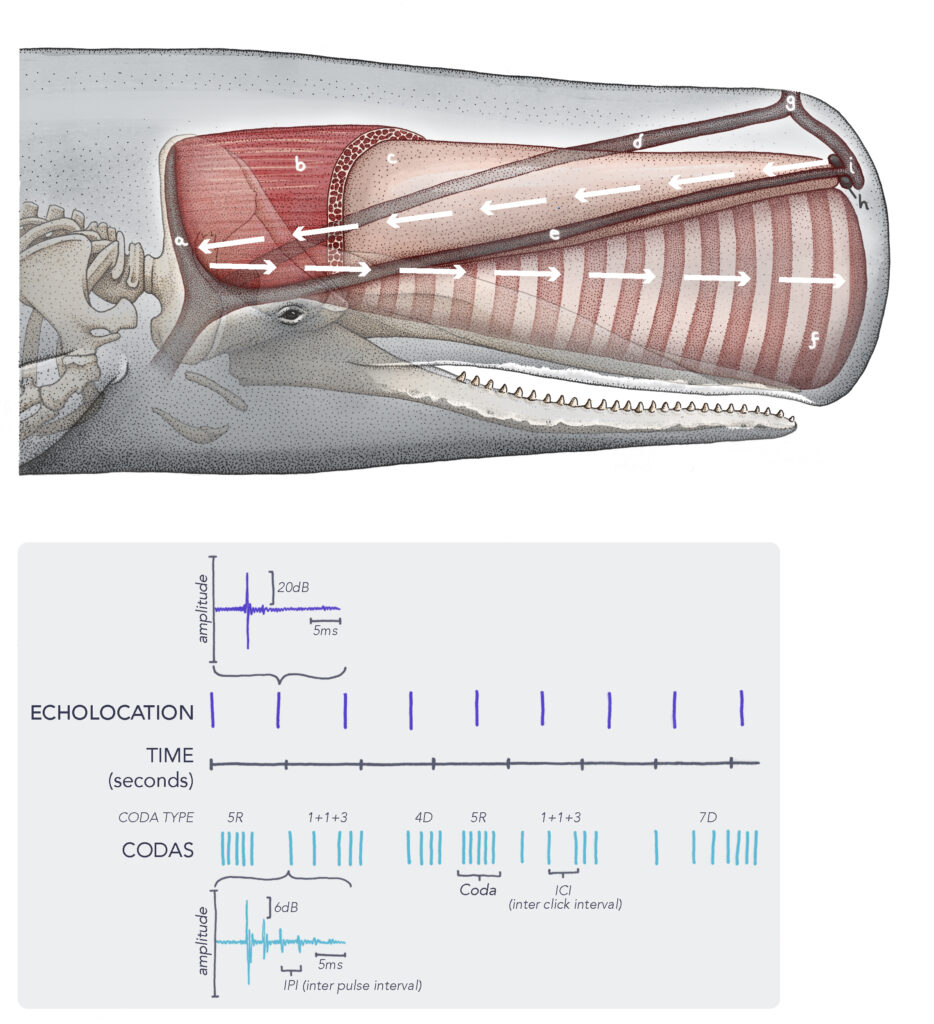

Using drones, on-whale sensors and hydrophones, the team records sperm whales’ communications, known as codas—rhythmic bursts of clicks produced when air is pushed through their nasal passages and over the “phonic lips” in their heads. The recordings are then fed into custom-built models—think ChatGPT for whales—to help researchers identify patterns.

CETI has already analyzed thousands of codas, uncovering a sperm whale “alphabet,” finding that click patterns shift with conversational context and learning that codas carry social meaning. All of these point to a complexity of communication far greater than previously believed. The whales even have dialects. Prior studies have shown that pods from different parts of the ocean vocalize as differently as a New Yorker and a Texan.

Gruber likens the team’s progress to climbing a mountain—each discovery offering a new foothold to ascend higher.

“The pieces,” he said, “are slowly coming in.”

From Corals to Whales and the Umwelt

Just before founding CETI, Gruber noticed something disturbing happening in the coral reefs he was studying. The tiny, soft-bodied anemone-like animals that make up coral reefs were changing in size and structure, just as their ancestors had 66 million years ago in the lead-up to Earth’s last mass extinction.

It felt, Gruber said, as if the corals were trying to communicate, sending a warning and preparing themselves for what’s coming.

“Here’s an animal without even a centralized nervous system, just a neural net, yet it’s adapting—doing what it needs to do to endure,” he recalled of the sobering discovery.

When Gruber published the finding in March 2020, it went largely unnoticed. Covid was surging, and attention was elsewhere. But for Gruber, the silence was familiar—humans’ indifference to the suffering of other species had broken his heart for years.

Then came the whales.

“The clouds have parted,” he said. “The fact that we’re getting people to even ask the question, ‘What is the whale saying? What are they thinking?’—I already feel like we’re making progress.”

In the paper, Gruber and his co-authors—CETI lead linguist Gašper Beguš and lawyers César Rodríguez-Garavito and Ashley Otilia Nemeth with New York University law school’s More-Than-Human Life program (MOTH)—explore what might happen if CETI succeeds.

Could decoding whale communications shift public apathy—and, as they put it, usher in a “new, immense legal world”?

The question is a nod to the 2022 book “An Immense World” by Ed Yong, which explores the concept of the “Umwelt,” the unique sensory world that every animal, including humans, inhabits, perceiving only a sliver of reality. The book offers a tour through hidden realms: bees reading ultraviolet light in flowers, bats echolocating prey and sea turtle hatchlings navigating by moonlight. The book shows how limited the human perspective on the world really is.

That narrowness has consequences. Humans’ inability, or refusal, to imagine other species’ experiences has led to suffering in ways most people barely register. Whales, the paper explains, are no exception.

Sperm whales and other cetaceans live in a world where sound replaces sight, where life depends on vibrations, and silence or noise can mean survival or death.

In that world, human noise isn’t an irritant—it’s a form of violence. The constant roar of ship engines and seismic blasts from military sonar, deep sea mining and fossil fuel operations inflict agony. Chronic exposure disorients whales, drives them from feeding grounds and floods their bodies with stress hormones. At higher intensities, the noise can cause internal bleeding and permanent hearing loss.

“A deaf whale,” the authors write, “is a dead whale.”

Laws such as the Marine Mammal Protection Act and Endangered Species Act have helped alleviate some of this suffering, but major gaps remain, MOTH lawyer Otilia Nemeth said.

In this vacuum, the global shipping fleet continues to grow, now more than 100,000 vessels strong, each one also a potentially lethal machine. Painful ship strikes kill around 20,000 whales each year. Many of those boats carry oil and gas, products whose use has driven oceans to absorb a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90 percent of the planet’s excess heat—acidifying waters, bleaching corals and driving species toward extinction.

Could all of this change if whales could tell us, in their own voices, the agony we inflict? Would we listen?

Gruber and his co-authors think so. History shows that when science deepens our understanding of other beings’ inner lives, society’s laws eventually follow.

“On the Origin of Species”

A decade before publishing “On the Origin of Species” in 1859, Charles Darwin confided to a friend that sharing his theory of evolution felt “like confessing a murder.”

The truth that humans evolved from a common ancestor with all other species didn’t just upend the biblical belief that God made humans uniquely superior—it threatened the economic systems built on human domination over nature.

Since then, each discovery about the intelligence, emotion and sentience of other species has chipped away at that hierarchy, reshaping public attitudes and, at times, the law.

For whales, a significant shift happened in the 1970s, when biologists Roger and Katy Payne released recordings of humpback whale songs—otherworldly, melodic exchanges unmistakably filled with meaning. The album’s impact was extraordinary, fostering a sense of connection between species and galvanizing the Save the Whales movement that led to the Marine Mammal Protection Act and a global moratorium on commercial whaling. (Roger Payne later advised CETI before his death in 2023.)

With that precedent in mind, Gruber began searching for a partner to explore the legal implications of CETI’s work.

Then he met Rodríguez-Garavito, the founding director of NYU’s MOTH program, in 2023 at a conference on designing a multispecies constitution. Rodríguez-Garavito—a key lynchpin for collaborations among scientists, Indigenous peoples, lawyers and others in the rights of nature movement—was the perfect partner.

What began as a casual conversation evolved into a two-year inquiry into how CETI’s science could help better enforce existing laws—and advance the rights of whales and the broader rights of nature movement.

Since emerging in the early 2000s, the legal branch of the rights of nature movement has shown how rights-based protections differ from traditional environmental law. Like human or corporate rights, they offer a higher level of protection—one that reflects society’s deepest moral values.

In Ecuador, whose 2008 constitution recognizes nature’s rights, judges have applied stricter standards—sometimes shifting the burden of proof to corporations and the government to show their actions won’t irreversibly harm ecosystems. Endangered frogs, protected forests and rivers have gone to court there, sometimes halting mining projects or other activities that threaten their existence. Advocates say the result is a legal system where nature, no longer relegated to the same status as a microwave or car, stands on more even footing with business interests.

The understanding that other parts of the Earth are living beings is hardly new. The CETI and MOTH paper notes that many Indigenous peoples understand personhood as “an experience common to all forms of life.” In New Zealand, for instance, Māori leaders have urged the world to recognize whales as legal persons—not resources for humans to exploit, but beings with rights.

What is Legal Personhood?

This legal category allows non-human entities such as corporations, nonprofits and ships to act in their own capacity under the law. The status allows businesses, for example, to enter into contracts, own property and, in the case of corporations, limit the liability of their shareholders.

For sperm whales, the authors argue, at least two such rights could be grounded in CETI’s science: the right to be free from torture and the right to culture.

Previously, the main way to know sound bothered whales was to observe their bloodied eardrums, Gruber said. “Now we can look at it through signatures in their voices.”

A right to be free from torture would go far beyond today’s anti-cruelty laws, which are riddled with loopholes and, as the paper puts it, “fail to capture the panoply of covert physical and psychological harm.” It would also acknowledge something deeper: how closely human and whale suffering align.

Courts have applied the human right to be free from torture in cases of sensory overload or deprivation—like when U.S. officials at Guantánamo Bay blasted detainees with deafening music for days. For whales, Rodríguez-Garavito said, human noise is the “equivalent of shining a blinding light straight into a human’s eyes, which is a form of torture.”

Courts have also recognized torture in the anguish caused by separation from loved ones. The paper points to the case of a mother named Juno, a North Atlantic right whale forced to watch her child’s “slow, agonizing death” from the slash of a ship’s propeller.

All legal rights seemed radical once. Before 1948, the human right to be free from torture did not exist.

A Right to Culture and a House of Cards

Just as humans suffer when their communities, traditions and ways of life are disrupted, so too do whales.

Sperm whales’ culture—migratory routes, dialects, learned foraging techniques and social rituals—is not instinct, but knowledge wrapped in communication and passed through generations, supported by lifespans that can stretch to 60 or 70 years.

“Culture isn’t what you do, but how you do it,” Otilia Nemeth explained.

From birth, whales are immersed in this living tradition. Calves “babble” before mastering their coda calls, echoing the stage when human infants learn to speak. Females assist in births and babysit one another’s young, while rhythmic patterns of clicks exchanged before hunts, during social gatherings and at births serve as both communication and ceremony—the social glue that holds their societies together.

For humans, a home or familial lands can anchor culture. For cetaceans, there is no fixed dwelling. “Everything is changing except their social lives,” the authors write, and constant motion forces whales to depend on one another for stability, making social bonds arguably even more vital than they are for humans.

Protecting sperm whales’ traditions, the authors argue, is the essence of their right to culture.

Human activities threaten this inheritance. Commercial fishing alone kills at least 300,000 whales annually as bycatch, disrupting the transmission of knowledge and language from generation to generation.

There’s enough clarity about the ongoing impacts that the authors ask why whales’ rights are not already recognized. Even so, they argue, “grasping the nuances of their communications” could deepen understanding of whales’ behavior, social lives, pain and health—and make their suffering harder to deny in the eyes of the law.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowRecognizing these rights isn’t only about whales, Rodríguez-Garavito said. It’s about self-preservation.

Humans, he said, “are embedded in the biosphere, entangled in the web of life that whales are also embedded in.”

Like a house of cards, the living world depends on each piece to hold the rest. Remove too many, or a few key cards, and the structure collapses.

The Last Hurdle of Separation

Across the constellation of court cases seeking legal personhood for nonhuman beings—from Sandra the orangutan in Argentina in 2014 to Happy the elephant in New York’s Court of Appeals in 2022—lawyers have often built their arguments on the human-like qualities these animals display.

For whales, those parallels run deep. Gruber notes that humans and whales diverged from a common land-dwelling ancestor some 90 million years ago. Humans remained on land; whales returned to the sea. Yet the two mammals still share scores of similarities: both breathe air, form close family bonds, transmit culture across generations and display self-awareness and problem-solving skills. And then there is language—long considered uniquely human.

“For a long time, we simply didn’t look,” said Beguš, CETI’s lead linguist. “We assumed animal communication systems had nothing to do with ours.”

The view began to shift decades ago when an African grey parrot named Alex astonished scientists by identifying more than 50 objects, understanding numbers and forming simple phrases. Alex and other animals showed they could master a foreign language—ours. Humans, Beguš noted, have yet to do the same in understanding another species’ speech.

Scientists still debate what language truly is and whether it belongs only to humans, the CETI and MOTH paper says. Some argue it depends on unique human mechanisms. Others see it as a product of cognitive abilities that evolved gradually, suggesting links between humans and other species.

Increasingly, evidence supports the latter view, Beguš said. Many hallmarks of human language, such as structured combinations of sounds and rhythm, also appear in communication of sperm whales and other nonhuman animals.

To probe those parallels, Beguš, who is also an expert in artificial intelligence, designed the custom models CETI uses. Unlike large language models trained on human text, CETI’s models are fed only sperm whale sounds and learn from acoustic data, not words. The models are intentionally small and “brain-like,” Beguš said, allowing researchers to peer inside and observe how they recognize linguistic patterns. So far, the team has identified between 100 and 600 distinct types of sperm whale codas, laying the foundation for future research into their meanings.

The combination of machine learning, which highlights where researchers should look, and human insight also helped CETI overturn the long-held assumption that sperm whale clicks were simply Morse code.

“When you look closely, you realize their sounds aren’t mechanical or random,” Beguš said. “They have structure, rhythm and now, we know, vowel-like elements—features we thought were uniquely human.”

Whales also communicate on a different time scale. Adjusting for that difference led CETI to its breakthrough discovery about the vowels. When researchers sped up whale codas, familiar speech-like patterns emerged, revealing the vowel-like sounds.

Stepping beyond a human-centered view of the planet, the paper argues, is crucial. Some scholars believe thought and language are intertwined, with humans using words to express their inner worlds. Whales, who experience and sense the world through sound, almost certainly think differently than humans do.

After countless hours spent listening to the codas, Beguš has become an unabashed advocate for whales’ rights.

“They have grandmothers, family bonds and conversations. They mourn their dead,” he said. “When you listen long enough, you realize their inner worlds might be as complex as ours.”

New Beginnings

In July 2023, CETI’s team witnessed something never before recorded.

In the blue waters of Dominica, 11 sperm whales from a close-knit unit gathered, at first appearing to simply socialize. Then, amid a chorus of codas, the head of a newborn emerged.

Newborns are perilously fragile. With less oil in their heads and a folded fluke, they sink easily and can drown, Gruber explained. But this calf did not sink. One by one, the adults surrounded the infant, taking turns, in pairs, to lift the newborn to the surface to breathe. They coordinated through clicks and calls, communicating constantly as they worked together for hours, until the fluke unfurled and the calf swam on its own.

Like with the biofluorescent turtle, Gruber feels the whales allowed the team to witness such a vulnerable moment because of the trust built through CETI’s non-invasive approach. The group collects data using suction cups rather than tags that pierce skin, and hydrophones that passively record sound, minimizing intrusion into the whales’ world.

Not all researchers take such precautions. MOTH also put forth a new proposal for legal and ethical guardrails around AI-assisted animal communication studies, which several organizations are pursuing with various species. The core of that paper, Rodríguez-Garavito said, is a framework of 12 ethical principles for scientists and companies developing these technologies to guard against potential misuse.

“Imagine what would happen if poachers use the vocalizations of animals to attract them, or whale watching operations unscrupulously using whale calls to basically use animals as entertainment for human beings,” he said. “Also, there are military uses.”

Rodríguez-Garavito stressed that MOTH’s collaboration with CETI isn’t about “mindlessly” chasing the dream of “breaking the interspecies communication barrier.”

“If that were the goal,” he said, “we wouldn’t be involved.” What interests him is developing the legal frameworks that could follow—standards that advance whales’ rights.

The obstacles to that are enormous, said Otilia Nemeth, MOTH’s other lawyer. “We as a society and as a species exploit the natural world for our benefit,” she said. “There are a lot of people and organizations and investors that stand to lose if there’s a fundamental reordering of legal personhood.”

Overcoming that, both lawyers said, will require weaving together science such as CETI’s with ancient knowledge of Indigenous peoples and legal expertise.

“To me this is a forward-looking, highly visionary initiative,” Rodríguez-Garavito said,

“but in an interesting way, it also harkens back to a distant past.”

The Heartbeat of the Ocean

At Climate Week in September, Gruber and Rodríguez-Garavito made their way into a packed NYU classroom to talk about CETI’s potential to advance rights for whales.

Yet it was another voice that stilled the room. Aperahama Edwards, a soft-spoken Māori leader of the Ngātiwai iwi (iwi means people), sat between Gruber and Rodríguez-Garavito, describing how the connection between his people and tohorā—whales—runs far deeper than mainstream law has yet to express.

“Our relationship with tohorā is implied with the essence of our being,” Edwards said. “We have an innate understanding of the significance of the whale, and we refer to the whale as an ancestor, we refer to the whale as an older sibling, carrying the heartbeat of the ocean.”

Twice a year, whales migrate through the waters of Aotearoa (New Zealand), and their journeys are observed and honored. When whales die or strand on shore, Māori elders conduct ceremonies to name and acknowledge them—a practice that, in the early 1980s, became a bridge between Indigenous knowledge and Western science.

During those rituals, elders began noticing distinctive markings and wounds, signs of trauma that revealed ships were striking whales. They brought in marine biologists, a collaboration that culminated in changes to shipping routes—an action that has yielded great success, Edwards said.

“It was a turning point,” he added. “Our cultural traditions and practices, alongside Western science and law, worked together to provide an enduring response to protect.”

Today, Edwards is part of a network of Pacific Indigenous leaders exploring a partnership with CETI and MOTH to help implement a landmark 2024 treaty among Indigenous peoples from New Zealand and the Cook Islands. The treaty, known as the He Whakaputanga Moana Declaration, recognizes whales as legal persons with specific rights.

For Edwards and other Māori leaders, that declaration isn’t a radical new concept but a continuation of ancestral responsibility—a reaffirmation that whales have always had their own place and agency in the world.

“It feels like an ongoing fight to recognize the rights of whales,” Edwards said. “But it’s part of our natural responsibility.

“For a long time, we’ve been careful in holding our ancestral knowledge, because it’s sacred. But the Western world has a lot to re-learn and un-learn. Our hope is that we can share some of that—to help steward this understanding forward.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,