In President Donald Trump’s first term, the federal courts helped put the brakes on his administration’s retreat on environmental protection.

Nine months into the second Trump term, the courts appear divided on whether to allow the administration’s far more aggressive dismantling of policy on climate change, clean energy and environmental justice.

In the 14 environmental policy cases so far in which there have been rulings on legal issues, the outcomes appear to be roughly even, with six clear wins for the Trump administration, five for the challengers and three mixed decisions, according to an Inside Climate News analysis. But in the Trump administration’s six victories, there’s an ominous sign: Three came when U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeal overturned lower court rulings. That means that as of Nov. 4, all of the appeals court decisions in environmental cases have gone the president’s way.

The most important appellate panel—the Supreme Court—has yet to weigh in on any environmental cases from Trump’s second term. But emergency orders the high court has issued on other issues—education and health, for example—portend trouble for the many lawsuits over the Trump administration’s wholesale termination of environmental justice grants.

The case outcomes are a sign that the environmental law battles of Trump’s second term will be different from those of his first term. They are playing out in federal courts that he has shaped with 251 appointments (his nominees hold 28 percent of 870 judgeships on courts established under Article III of the Constitution). And in the years Trump was out of office, his judicial appointees helped transform the laws governing federal regulation, giving agency decision-makers less deference and narrowing the scope of their authority. The changes have emboldened Trump’s second-term team leaders, like Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lee Zeldin, to push the envelope, including with a bid to rescind his agency’s authority to address climate change.

But all of the second-term court rulings so far have been on preliminary issues—mainly whether to put a hold on Trump administration actions while core case issues, such as constitutionality, are decided. Moreover, in the vast majority of environmental cases involving the Trump administration, there have been no substantive rulings so far.

“It’s far too early to tell how they’ll go,” said Michael Gerrard, founder and faculty director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. “The three where the courts have denied preliminary injunctions have gotten attention, but it’s only three” out of a much larger number of cases, he said. Gerrard compiled a list of environmental cases for Inside Climate News, based in part on the Sabin Center’s Climate Litigation Tracker.

Even if the second Trump administration is a more challenging legal environment, environmental advocates and Democratic state attorneys general are pushing forward with litigation, arguing that Zeldin and other Trump policymakers have overplayed their legal hand. And they maintain there’s reason to believe the courts ultimately will curb Trump rollbacks, especially on important regulatory issues, like the proposed repeal of the EPA’s endangerment finding on greenhouse gas emissions, that are yet to be finalized and litigated.

A Changed Legal Landscape

Records show challengers were successful in holding back many of the first Trump administration’s gambits to roll back environmental protection. One advocacy group, the Natural Resources Defense Council, says it sued the first Trump administration 163 times, winning nearly 90 percent of its cases. NRDC’s suits helped put a stop to the first Trump administration’s effort to restart the Keystone XL pipeline, to open areas of the Arctic and the Atlantic oceans to drilling and to eliminate energy efficiency standards.

The litigation tracker of the Institute for Policy Integrity at New York University, which zeroed in on regulatory disputes, showed that 76 percent of 135 court cases over agency environment, energy and natural resources rules were decided against the Trump administration between 2017 and 2021. Courts in those cases, for example, determined that the Trump EPA failed to follow the law in its weakening of rules on the potent greenhouse gases known as HFCs, on its handling of toxic wastewater discharges from power plants and in its delay of rules on methane emissions from landfills.

Tracking The Cases

Inside Climate News is watching the progress of federal court cases on Trump’s climate and environmental policy. Here’s a look at the lawsuits and the outcomes so far.

The current array of environmental policy cases is quite different from the mix in Trump’s first term, reflecting how much policy he has sought to make through executive action, without resorting to the formal regulatory and deregulatory process. For example, there are four challenges related to Trump’s executive orders to halt offshore wind energy development before the courts—and in one of those cases, the Revolution Wind project off Rhode Island succeeded in getting an injunction lifting Trump’s stop-work order and allowing it to resume construction.

Trump’s assertion of executive authority on renewables decision-making cuts both ways; the administration has been sued by two anti-wind-energy groups over its decision to allow another offshore project, Empire Wind, to proceed. A U.S. district judge in Washington, D.C. ruled on Oct. 23 in favor of the Trump administration, which is a win for Empire Wind.

A district judge in Washington state has blocked, for now, the Trump plan to suspend the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure charging network, known as NEVI. And a district judge in New York ruled that New York City’s new congestion pricing program should be allowed to go into effect while litigation over whether Trump has power to stop it proceeds.

Although the cases are varied, observers see common threads in the executive actions at issue.

“The theme that runs throughout is they’re doing everything they can to maximize both the supply of and the demand for fossil fuels,” Gerrard said.

In four cases, the Trump administration is directly challenging states’ authority to pursue their own climate policy. The Justice Department is seeking to overturn the climate “superfund” laws of Vermont and New York, and to block Michigan and Hawaii from suing fossil fuel companies to recover climate change costs, such as the expense of infrastructure to address sea level rise and to protect populations from extreme heat events. There have been no rulings in those cases so far.

One case that embodies the division among federal judges ruling on Trump environmental policy is the challenge to his siting of a migrant detention camp in the Everglades. The property known as “Alligator Alcatraz” is in the midst of wetlands that filter and store water for millions of Floridians, land that is sacred to Florida’s Miccosukee Tribe. A federal judge on Aug. 22, acting on a request by the tribe and environmentalists, ordered that the facility be dismantled and wound down. But in a 2-1 decision on Sept. 4, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals temporarily lifted that order, while the courts decide if an adequate environmental review was conducted. The two judges who sided with the Trump administration were among the six Trump appointees on the 12-judge 11th Circuit, which hears appeals throughout the Southeast.

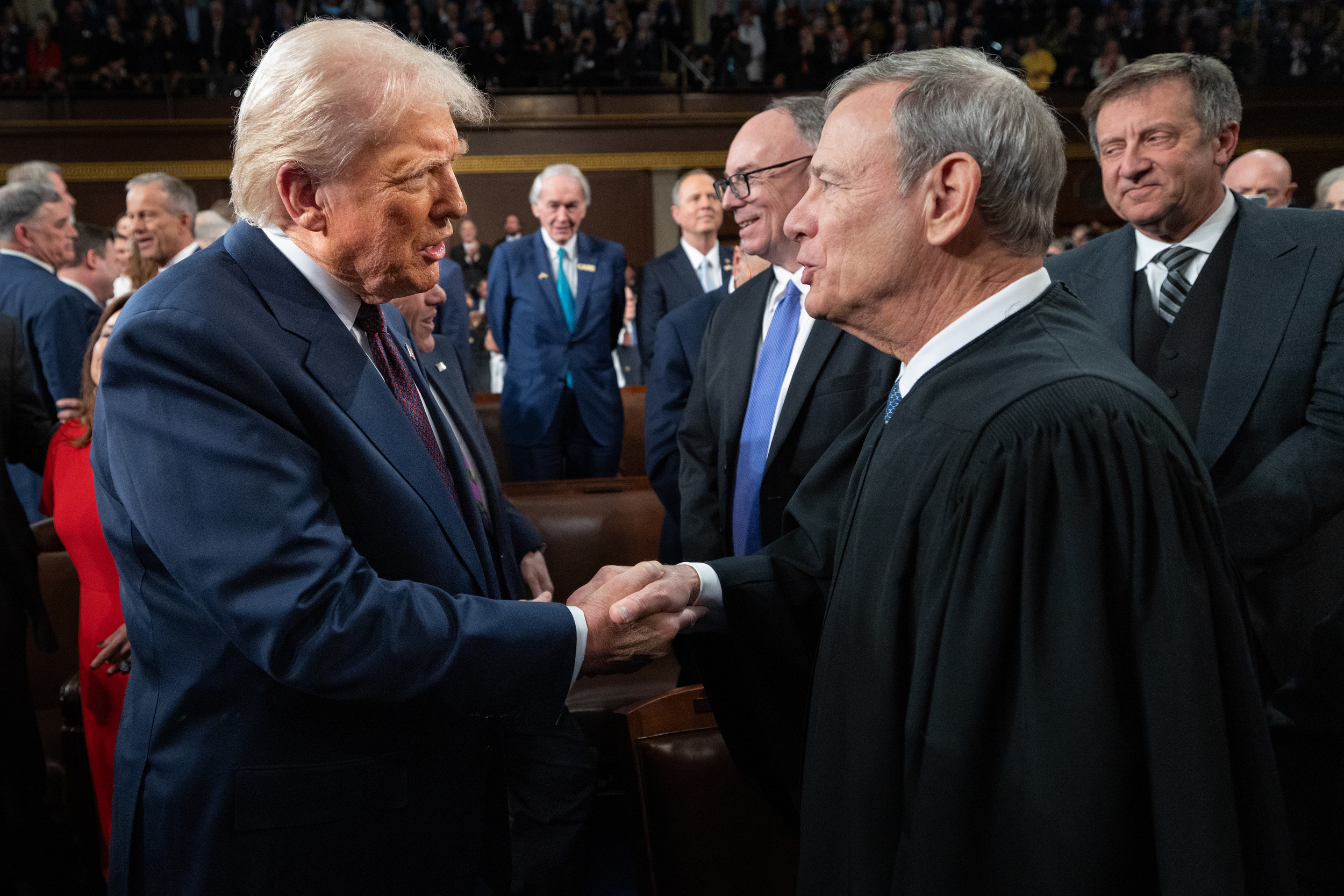

The federal judicial system was designed to insulate judges from politics, requiring that appointees be confirmed by the Senate and be given lifetime appointments. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts has vociferously defended the judiciary’s independence, declaring in 2018, “There are no Obama judges or Trump judges,” but “an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.”

Nevertheless, legal scholars have documented the partisan shift in judicial philosophy on the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority bolstered by three Trump appointees. And litigants are increasingly choosing where they file challenges against the federal government based on the political leanings they perceive in the Circuit Courts of Appeal, according to data compiled by the Institute for Policy Integrity.

The 177 active U.S. Courts of Appeal judges are closely divided in terms of appointees of Republican (51 percent) and Democratic (49 percent) presidents overall. But there are stark regional differences, with Republican presidential appointees holding 91 percent of the seats on the 8th Circuit in the Mountain West, and Democratic appointees holding 100 percent of the judgeships in the 1st Circuit in New England.

In the federal trial courts, (known as district courts), usually the first step in the legal process, Democratic appointees hold 61 percent of the 626 active judgeships, compared to Republicans’ 39 percent. And some decisions by Republican-appointed district judges have gone against the Trump administration. For example, Revolution Wind won its injunction from U.S. District Judge Royce Lamberth in Washington, D.C., an appointee of President Ronald Reagan.

And U.S. District Judge William Young in Massachusetts, another Reagan appointee, issued an order in June blocking the Trump administration’s cancellation of 2,100 National Institutes of Health grants. The Trump administration petitioned the Supreme Court and got an emergency order to reverse Young’s decision. Although not specifically an environmental case, that outcome now has bearing on one of the largest environmental case categories being litigated in Trump’s second term. The Trump administration is arguing, and a number of judges are agreeing, that the district courts have no jurisdiction over challenges to his administration’s termination of billions of dollars of grants, mostly for disadvantaged communities.

A Grenade From the Shadow Docket

At least nine lawsuits are underway over the Trump administration’s termination of the green bank and environmental justice and clean energy grants that Congress authorized in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021 and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. The grant cancellations are erasing one of President Joe Biden’s most important climate initiatives.

Grantees scored early wins, with federal judges in Maryland, Rhode Island, South Carolina and Washington, D.C. ordering funds released while the legal challenges are heard. “EPA contends that it has authority to thumb its nose at Congress and refuse to comply with its directives,” wrote U.S. District Judge Adam Abelson, a Biden appointee, in deciding the Maryland case. The cases raise serious constitutional issues as well as statutory ones—in the South Carolina case, for example, the issue of whether grantees had been illegally targeted because of their viewpoints in violation of the First Amendment.

But since June, environmental grantees have seen a slew of defeats. The shift came after a divided Supreme Court issued two emergency orders favoring the Trump administration in its cancellation of education and NIH grants. A 5-4 majority of the high court backed the Trump administration’s view that such lawsuits were simple breach-of-contract matters that should be decided in a specialized venue, the Court of Federal Claims.

The rulings were consequential. The Claims Court only has the power to award money to grantees, not to reinstate terminated programs or decide on the big legal issues that the grantees have raised. For example, it has no authority to rule on charges that the Trump administration acted unconstitutionally or violated laws such as the Administrative Procedures Act, which is meant to protect citizens from “arbitrary and capricious” government actions. Ten of the 16 active judges on the Claims Court were appointed by Trump.

And because the Supreme Court took these cases from its emergency docket—its “shadow” docket, as critics call it—the big legal issues were barely aired. “Barebones briefing, no argument, and scarce time for reflection,” said Justice Elena Kagan in her dissent in the education grants case, chiding the majority from making new law from the emergency docket, as the court has done increasingly in recent years. Another dissenter, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, called the majority’s ruling on the education grant terminations “equal parts unprincipled and unfortunate,” and in the NIH case, she lamented that “a half paragraph of reasoning” was justifying cutting off millions of dollars for life-saving biomedical research, and had the potential to derail other grantees raising similar claims.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe Court, she said, “lobs this grenade without evaluating Congress’s intent or the profound legal and practical consequences” and is “sending plaintiffs on a likely futile, multivenue quest for complete relief.”

In three environmental grants cases so far—two in the appeals courts and one in the Washington, D.C. district court—judges have followed the Supreme Court majority’s reasoning, saying the cases likely belong in the Claims Court. The rulings have stymied efforts to save one of Biden’s largest climate programs, the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. This so-called “green bank” was designed to act as a revolving fund, providing low-interest loans to give disadvantaged communities access to financing for renewable energy and efficiency upgrades. Initially seeking to claw back $20 billion of the fund, the EPA’s Zeldin leveled allegations of corruption against the recipients and the Biden administration. A lower court judge said the EPA had not offered any evidence of wrongdoing, and ruled that the funds should be released, before she was overturned by a 2-1 vote of a panel of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals. The two judges who sided with Zeldin were Trump appointees.

Now, some grantees are trying to be proactive in anticipation that judges will move their complaints to the Claims Court. On Oct. 15, a coalition of states launched a two-pronged legal attack against Zeldin’s August cancellation of the remaining portion of the green bank fund, the $7 billion Solar for All program, by filing lawsuits simultaneously in the district court and the Claims Court. The move puts a large environmental grant program in line to be the first adjudicated in the Claims Court. The Solar for All case could become an early indicator of what kind of money damages, interest and attorneys fees the United States Treasury may be forced to pay because of the Trump administration’s wholesale termination of grant programs.

For now, most climate and environmental justice grant recipients have been denied access to their funds. But the grantees believe the Supreme Court has offered a narrow window of opportunity to have their legal issues heard. Roberts sided with the liberal justices in ruling that challenges to the grants’ terminations should not be funneled to the Claims Court. And Justice Amy Coney Barrett provided a crucial swing vote in the NIH grant ruling; joined by Roberts and the three liberal justices, Barrett said the plaintiffs could still challenge the Trump administration’s internal agency guidance determining which grants were cancelled.

Jackson expressed doubt as to whether Barrett’s compromise provided any meaningful opportunity for the grantees to have their claims heard: “It splits review of the grant terminations from review of the grant termination policy—thereby preserving the mirage of judicial review while eliminating its purpose: to remedy harms,” Jackson wrote in her dissent.

Nevertheless, arguments were heard in the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals on Oct. 23 seeking to revive the South Carolina case and its claims that the Trump administration had acted unconstitutionally.

Counting on Judicial Independence

To affirm the value of pushing back against Trump in the courts, some environmental advocates can point to wins they obtained just by filing lawsuits that brought to light the impact of Trump administration actions. After the Northeast Organic Farming Association of New York filed suit, the U.S. Department of Agriculture in May restored climate-smart agriculture information it had purged from its website. (Among the pages that were missing for a time were those that helped farmers access billions of dollars in support for conservation practices.)

And after the Environmental Defense Fund filed a lawsuit, the U.S. Department of Energy disbanded a committee of five well-known climate science deniers it had assembled to produce a controversial review of climate science. EDF argued that the creation of such a secret committee was a clear violation of the transparency and fairness mandates in the 53-year-old Federal Advisory Committee Act. The Trump administration has argued that the case is moot now that the committee is disbanded, but EDF is continuing the litigation.

“If the administration had followed federal law, full records of the deliberations and meetings of the climate working group would have been made available,” said Vickie Patton, general counsel of the EDF. “We believe that the American people are entitled to those records, and we are going to continue to press for them.”

Asked if she was concerned about whether the federal courts, with so many Trump appointees, would serve as an effective check on Trump in his second term, Patton expressed confidence in the system. “Our experience has been that there are courts and judges that are stewards of the rule of law and operate with the highest degree of integrity,” she said. “And I think everyone should ask that of our judiciary and our judicial system. It’s vital for our constitutional democracy.”

The most important challenges to Trump’s environmental rollbacks will come when federal agencies finalize their deregulatory proposals, including EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin’s pledge to wipe 31 pollution rules from the books.

A key case to watch will be the inevitable legal challenge to Zeldin’s planned repeal of the EPA’s 16-year-old finding that greenhouse gases endanger human health and welfare, the foundation on which all of the EPA’s other climate rules are based. Zeldin’s proposal leans heavily on a series of decisions that the Supreme Court has delivered in the past three years that limit an agency’s authority to act without explicit direction from Congress, especially in matters of great economic significance: the court’s so-called “major questions doctrine.”

“We can no longer rely on statutory silence or ambiguity to expand our regulatory power,” the EPA said in its proposal.

Climate action advocates will argue it was the Supreme Court itself that ruled in its landmark 2007 Massachusetts v. EPA case that greenhouse gases fit the definition of “pollutant” under the Clean Air Act, and directed the EPA to lay out its reasoning for or against regulation grounded in the language of that law. In the wake of that ruling, the Supreme Court rejected bids to overturn the endangerment finding, and ruled to limit state actions on climate change specifically because the EPA has the governing authority over climate regulation. But the five justices who decided the case for Massachusetts are dead or retired. Three of the dissenters, Roberts and Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito, remain on the court, along with three Trump appointees who have voted for limited EPA power on climate change.

Nevertheless, if the Supreme Court were to now agree with the Trump administration’s view that the EPA never had the authority to act on climate under the Clean Air Act, it could unravel all of the case law on the subject since the Massachusetts decision.

“They’re betting that they can get the current six-member majority to say, ‘We don’t care about Massachusetts, and frankly, we don’t care about the three other climate decisions we made that built on and accepted Massachusetts,’” said David Doniger, senior attorney and climate and energy strategist for NRDC. “They’re betting the court is just going to bless the Trump administration doing whatever it wants and I don’t think that kind of lawlessness is going to prevail.”

The EPA has received more than 568,000 public comments on its endangerment finding repeal proposal, and the law is clear that the agency must provide a “reasoned response” to any substantive comments. In fact, the Supreme Court last year blocked the Biden administration cross-state air pollution rule from taking effect, ruling that his EPA had failed to adequately address public comments.

All eyes will be on whether the Supreme Court holds the Trump EPA to the same standard.

“I count on the independence of the courts,” Doniger said. “We’re all counting on that for so much.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,