In a recent science briefing, some of the world’s leading climate researchers said that accelerated warming over the past 10 years is a warning that Earth’s natural carbon-absorbing systems, including forests and oceans, are breaking down in the face of relentlessly rising greenhouse gas levels from fossil fuel emissions.

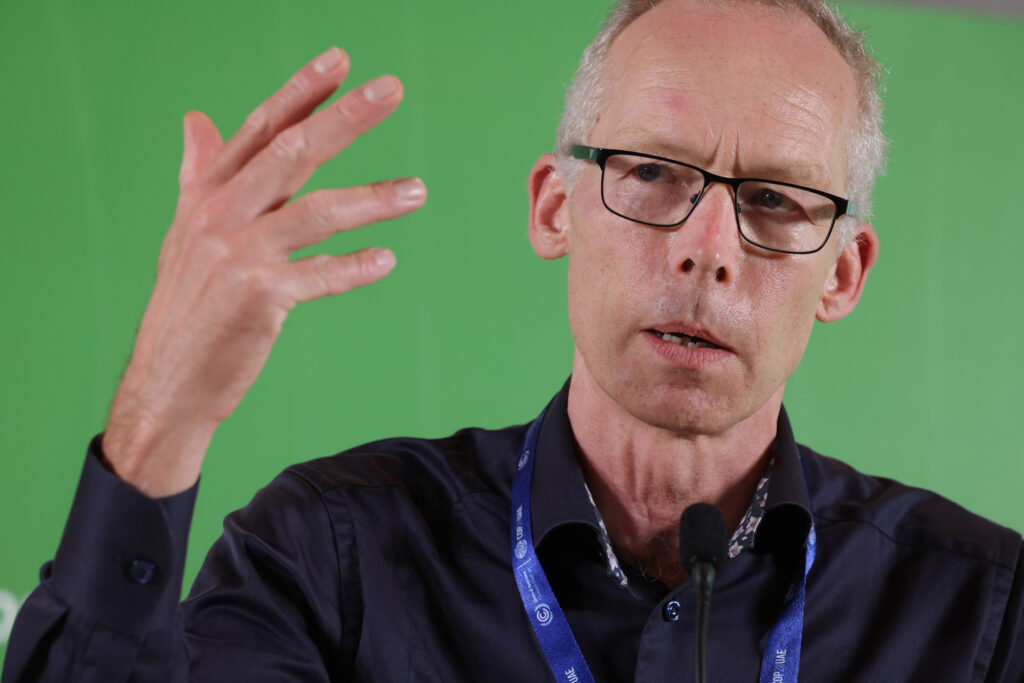

Last week’s presentation, led by researchers with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, was aimed at the negotiators gathering for the COP30 climate talks in Belém, Brazil, from Nov. 10 to Nov. 21. The institute’s director, Johan Rockström, said “one of the messages is that we are forced to declare failure, because we will inevitably, within the next five to 10 years, breach the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit set in the Paris Agreement.”

Failure to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the decade since the Paris Agreement has added more heat to the pipeline that, by 2050, will push the global temperature “somewhere up to 1.7, potentially 1.8 degrees Celsius” above the late-1800s global average, Rockström said. That period set the baseline temperature against which human-caused warming is measured.

A new briefing from Oil Change International, a nonprofit fossil fuel industry watchdog group, suggests that four countries—the United States, Canada, Australia and Norway—carry an especially hefty fossil fuel burden. While the rest of the world reduced oil and gas output since 2015, when the Paris pact was finalized, those four countries increased production by 40 percent.

Rockström said dangerous warming of around 1.7 to 1.8 degrees Celsius is coming whether or not fossil fuels are phased out by 2050, and “even if natural carbon uptake stays stable and we scale up carbon dioxide removal technology.”

Signs that land ecosystems, such as rainforests and boreal forests, are losing their capacity to absorb carbon are especially worrisome, he added. It means the planet is losing its ability “to cope with the disturbance caused by our greenhouse gas emissions, which would change very much the pace by which we have to decarbonize the global economy,” he said.

Protecting natural ecosystems, he added, is key to preventing Earth’s climate from “drifting away toward self-amplified warming.” In that scenario, the planet would continue to heat even if greenhouse gas emissions stopped, a process that could become irreversible.

At the current warming level, which is about 1.2 degrees Celsius above the baseline, nearly “every corner of the biosphere is reeling from intensifying heat, storms, floods, droughts, and fires,” an international team of scientists wrote in a related paper, also released last week. Earth is already “hurtling toward climate chaos,” they wrote, and “the unfolding emergency stems from failed foresight, political inaction, unsustainable economic systems, and misinformation.”

All signs point toward climate extremes, including heat waves, wildfires, disease and precipitation, becoming more intense and more frequent, said Rockström, who co-authored the paper. “We can say with essentially 100 percent certainty that we will have a rougher time before it potentially gets better,” he said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowCarbon Tax Alliances Could Spur Climate Action

Even before the Paris Agreement, science showed that cutting carbon dioxide emissions from energy, transportation and industry, as well as forestry and agriculture, is the only effective way to tackle the climate crisis.

Ottmar Edenhofer, another director of the Potsdam Institute, said recent climate economics research shows some fiscal policies could help even at a time when rising global political and economic tensions are hampering the consensus-based approach of COP30 and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.

Given that global consensus on climate policy seems unlikely at COP30 or in the next few years, Edenhofer said he thinks it would be a “great outcome” if future COPs provided a forum for groups of countries to discuss fiscal measures related to CO2 emissions and administer the revenues.

As one of the world’s largest economic blocs, he said, the European Union has the potential to influence global climate and energy policy with a “carbon border adjustment mechanism” that imposes a CO2 tariff on imports from countries that don’t charge for greenhouse gas pollution—what’s known as a carbon price. By doing so, it encourages other countries to adopt their own carbon pricing so they can keep the revenue rather than paying it to the EU.

Other economic powers such as Japan, Turkey and Korea, he said, “would have an incentive to join, even if the U.S. is not part of the club,” he said. “From my point of view, the task for Europe is to facilitate cooperation even in a time of geopolitical risks.”

Edenhofer said current discussions about carbon taxes on aviation and shipping could also help cut emissions significantly. These taxes have the potential to raise up to $140 billion per year for climate finance, far more than is currently pledged through various funds. Using some of the money for carbon removal technologies links carbon taxes with climate finance and emission reductions.

The Potsdam Institute’s climate finance models also showed that a coalition of major fuel-importing countries could tax fossil fuel imports to generate new revenue for climate programs. Acting together would curb demand enough to push global fuel prices down, easing costs at home while funding mitigation abroad, he said.

The COP presidency has asked the Potsdam Institute to host the first-ever official science pavilion in the heart of the negotiation zone, said Rockström, who will co-chair the pavilion with Carlos Nobre, a Brazilian ecologist sometimes known as the guardian of the Amazon. The goal is to raise the voice of science at COP30 and to “create a closer interface between the science and the negotiations at large,” Rockström said.

Ten years ago, when the Paris Agreement was celebrated, “We still had a carbon budget and a room for bending the curve of emissions by 2020 and then moving along a much, let’s say, more orderly pathway to stay away from 1.5 degrees Celsius,” without exceeding the 1.5 degree Celsius target, he said. “Now, 10 years later, we have failed and we are at a point of danger.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,