Residents in an upstate New York community are trying to prevent construction of a planned data center by approving a year-long ban on large-scale development.

Data center company TeraWulf has signed an 80-year lease for 183 acres of a former coal-fired power plant, which sits on the banks of Cayuga Lake in Lansing, a town of 11,000 just north of Ithaca in New York’s Finger Lakes region.

Many Lansing residents are concerned that the data center will raise electricity costs, generate noise pollution and drain the region’s water resources.

The town board is scheduled to vote this month on a proposed moratorium that could derail TeraWulf’s plans.

According to a company filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission, TeraWulf has the right to develop up to 400 megawatts of data center capacity there. In context, the center would be capable of sucking up around 16 percent of the total power capacity of the Robert Moses Niagara Hydroelectric Power Station, the state’s largest power producer and the second-largest plant of its kind in the country.

Lansing resident Aaron Guilbeau, who lives on the banks of Cayuga Lake close to the proposed site for TeraWulf’s data center, is worried about hearing the low hum of the data center from his home, and that the value of his property would drop as a result.

Like many in Lansing, Guilbeau believes that the center will affect his quality of life and utility bills. He is not alone. Hundreds of residents have submitted public comments, many of which raise possible issues with water use and noise. They have also flocked to public meetings about the moratorium to criticize TeraWulf and the data center industry.

Union members and some business leaders, however, support the data center, excited about the prospect of new construction and maintenance jobs the site could bring to the area.

“These are good jobs,” said David Emmi, the vice president of O’Connell Electric, an electrical contractor based out of upstate New York, at a town board meeting in September. “It really is a great thing for the community.”

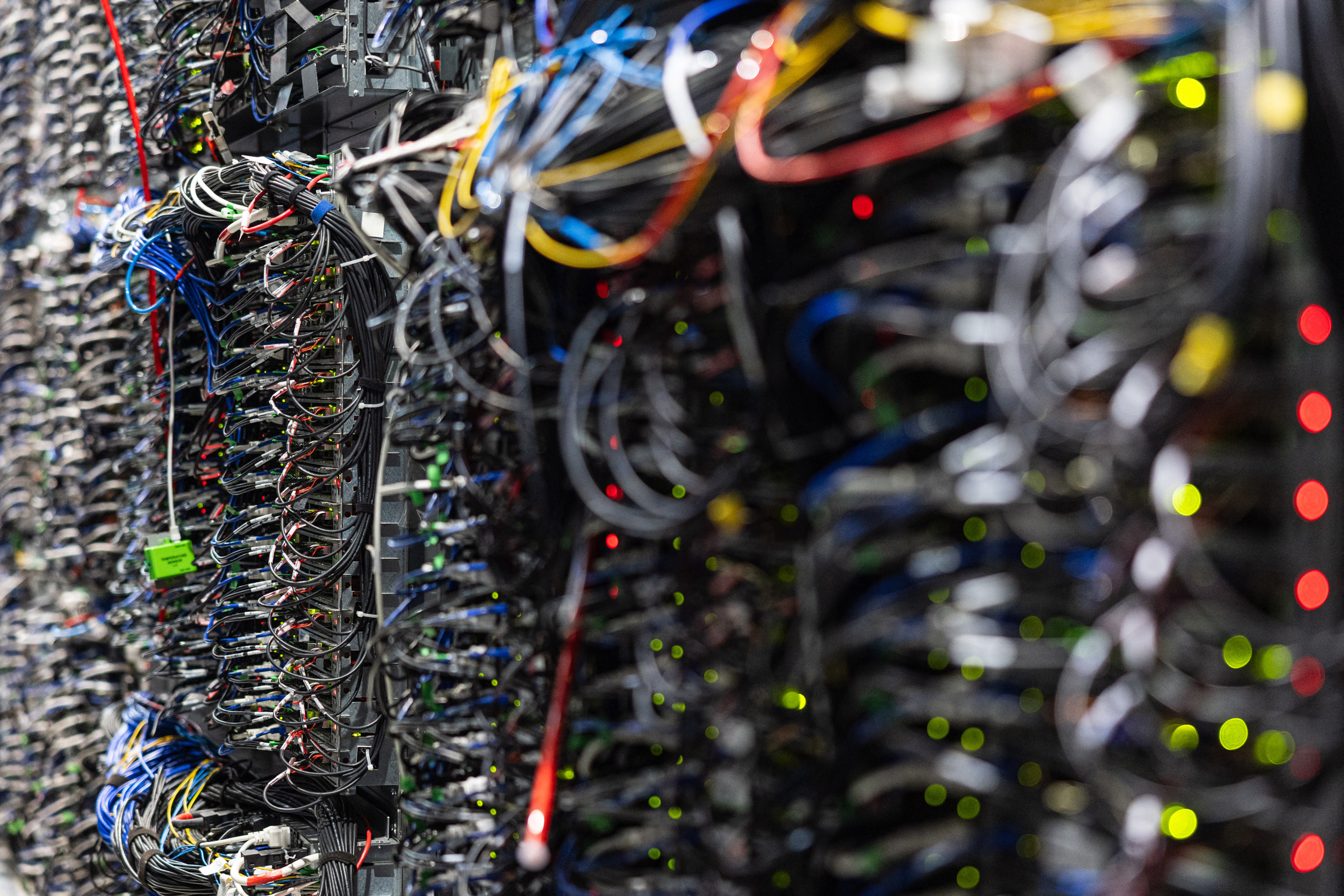

But residents’ reservations are not unfounded. Data centers often need significant amounts of water to cool their computers—for some, that means hundreds of thousands of gallons.

The site of the former coal plant where TeraWulf wants to build the data center has an existing water intake system that feeds from the lake. Lansing residents were concerned about the data center using that water, especially since TeraWulf mentioned the pipe in a statement to investors.

At nearby Seneca Lake, a cryptocurrency mining center—which also needs water to cool computers—sucks up water from the lake and releases it back into the lake at much higher temperatures. Residents there worry it could contribute to harmful algal blooms, a toxic growth that occurs in ponds and lakes at elevated temperatures.

In a letter to the town board, TeraWulf said that it will not rely on Cayuga Lake to cool its computers. In an email statement, a TeraWulf spokesperson said that the facility will use “a fully closed-loop cooling system” that circulates water and a food additive called propylene glycol to cool the data center computers. The heat from the data center is transferred to a secondary water loop, which is cooled by large fans.

During the site’s operations, the spokesperson wrote, “the system is sealed, it does not consume or discharge water.” The coolant can remain in the system for seven to fifteen years, according to the spokesperson, without requiring replacement or recharge.

At an event organized by TeraWulf to engage residents, Sean Farrell, the company’s chief operating officer, touted the system’s benefits. Farrell also told residents that to cool a 50-megawatt building, TeraWulf would use around 250,000 to 300,000 gallons on the first day of operations.

After that, water would only be needed for “periodic maintenance or negligible replenishment due to evaporation within the sealed system” a spokesperson said.

Many data centers cool their computers by running water through a system and then dump it back out at elevated temperatures, with some water lost due to evaporation. A dry cooling system like Terawulf’s, which uses air to keep temperatures low, requires much less water than other cooling systems, because it recycles water and very little evaporates, according to the European Climate Adaptation Platform.

But this type of cooling can require significant energy to keep the fans running, according to the Energy Information Administration which examined the use of these systems in power plants. The system may also struggle to reject heat during warm weather because the difference between the outside temperature and the computer heat is minor.

Data centers are also known to emit a near-constant low-frequency hum that neighbors often hear. Farrell said the company has chosen “ultra-low noise” coolers for the site that are designed to operate at a lower decibel level than traditional systems.

TeraWulf operates a cryptocurrency mining center facility in Somerset, New York, where residents have long complained about the noise. In response to these criticisms, Farrell said the company has “implemented noise reduction solutions” and has conducted tests showing that noise from the facility does not reach these residents’ property.

On its website, TeraWulf says it operates “state-of-the-art infrastructure that fuses advanced computing technologies with sustainable energy.” At his company’s event, Farrell discussed the “abundant zero-carbon power” in the region, suggesting that the data center will be powered primarily by renewable energy.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe New York State Energy Research and Development Authority has said that upstate New York’s power mix is “approaching 90 percent emission‐free.” But there is no way to know where the power for TeraWulf’s proposed new data center would be coming from because it is connected to the state grid, not an individual power source, a spokesperson for the state’s grid operator said.

Kristin Maushart, who has lived in Lansing for 11 years, had never attended a town board meeting before. But she lives six miles from the proposed data center, she said, and fears the data center will mean higher electricity rates. So on Sept. 24, she made her way to a meeting.

“When I got there, the line was literally out the door,” she said. “I had to wait an hour, actually, to get into the room.”

Because data centers consume so much electricity, utilities may have to upgrade power lines or other grid infrastructure to supply more power to these sites. Even if the centers pay for connection to the grid, as they do in New York, there may also eventually be infrastructure upgrades needed in other areas of the state’s grid—and the cost of that is often passed on to ratepayers.

Additionally, rising demand for electricity can also cause an increase in prices. A recent blog post by the New York Independent System Operator, which operates New York’s grid, said that “electrification and data center growth drives up prices and prompts calls for accelerated investment in new resources.”

The operator also said that the state could face reliability issues as early as next year due, in part, to the additional demand from data centers.

One report from the state grid operator predicted that, by 2030, electricity demand could increase by an additional 1,600 megawatts to nearly 4,000 megawatts because of large power drains such as data centers and building electrification across the state.

The TeraWulf spokesperson said that the data center at Cayuga Lake will curtail power use during peak demand to help stabilize the grid. The company expects to “invest approximately $15 million in local electrical infrastructure upgrades to enable safe interconnection and strengthen grid reliability for the first 138 [megawatts].”

Ultimately, many Lansing residents are not convinced that this will be a boon for their town.

“I don’t believe that they are a partner of our community,” said Maushart. “I think it’s a mega-corporation—I think they’re here to extract resources from us. … They represent their best interests, which are their stakeholders and their customers.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,