BESSEMER, Ala.—When Yale biologist Thomas Near and members of his research team visited the Yellowhammer State in October, the state’s famous Dreamland BBQ wasn’t the only thing on the agenda, though it was high on the list.

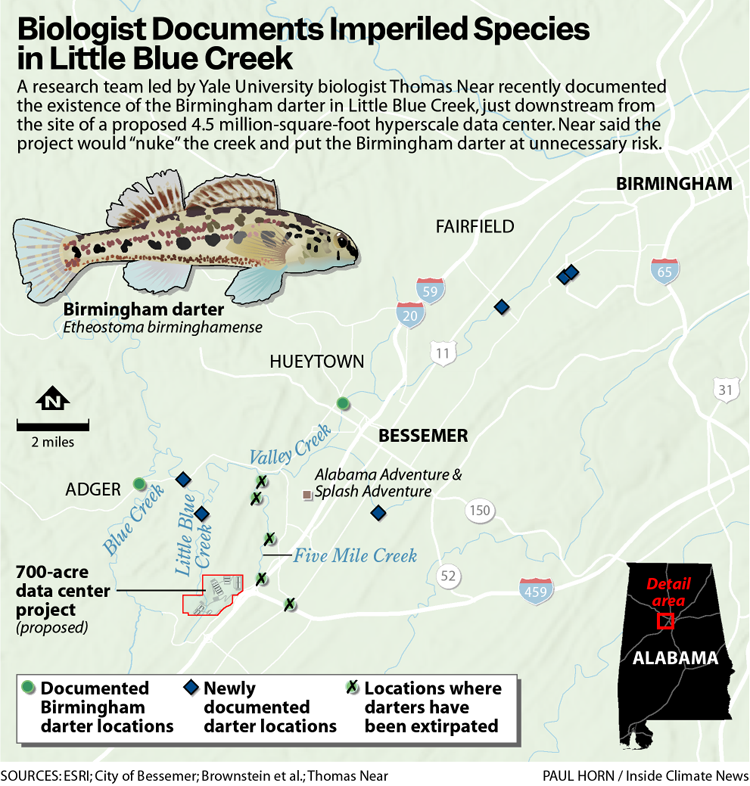

During their trip, the researchers documented the existence of the Birmingham darter, a newly identified fish species, just downstream of the site of a proposed 4.5 million square foot hyperscale data center, the construction of which Near said would put the already imperilled species at risk of extinction.

On Thursday, based in part on Near’s research, the Center for Biological Diversity, a national environmental nonprofit, filed a petition with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service asking that the agency list the Birmingham darter as an endangered species under the Endangered Species Act, providing the fish the legal protections experts have said its precarious existential position demands. The federal agency has 90 days to respond to the nonprofit’s petition and decide “whether the petition presents substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action may be warranted.”

Developers of the proposed data center have previously asserted that the species is not present on its project site, though neither council members nor the project’s developers have publicly released any environmental assessments related to the project.

The Bessemer City Council is scheduled to vote on final approval of Project Marvel on Tuesday at 9 a.m.

A representative of the developer did not respond to a request for comment on this story.

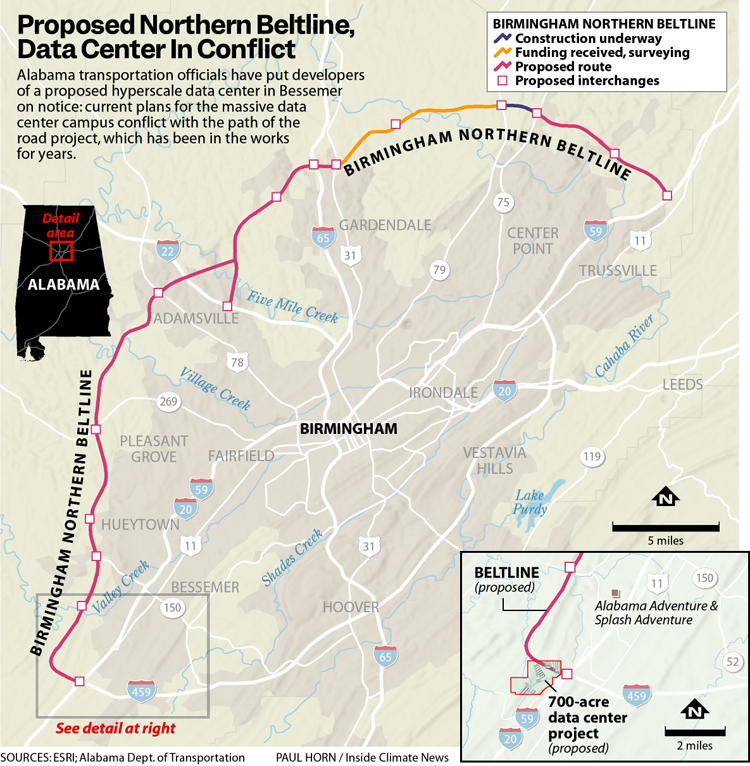

The presence of the darter is not the only problem ahead for those behind the project. The director of the Alabama Department of Transportation has notified the engineers of the data center proposal, known as Project Marvel, that the current plans for the data center campus conflict with plans for the Northern Beltline, a multi-billion dollar highway project that state and federal officials have pushed for years.

These updates—on both the Birmingham darter and the Northern Beltline—present potential obstacles for Logistic Land Investment, LLC, the developer pushing the data center project, and provide a potential lifeline for nearby residents, who are almost universally opposed to the massive construction project slated for their backyards.

“All Fecal Matter Rolls Downhill”

Near is no stranger to the Birmingham darter. He was part of the research team that first identified the small, colorful fish as a species distinct from other, similar species that live in the surrounding areas of north-central Alabama.

Now, Near said he and his colleagues have done the necessary field work to show that the fish, scientific name Etheostoma birminghamense, is present in Little Blue Creek, which flows through the site of the proposed hyperscale data center in Bessemer, a suburb just southwest of Birmingham.

“They’re there,” Near said of the Birmingham darter on Monday. “And anything that happens upstream is going to have an effect on them.”

Near and his colleagues were unable to visit the data center site itself, which is privately owned, but the biologist said there’s little doubt that if the development moves forward, it could put the newly identified species at risk of extinction.

“It’s a crude saying, but all fecal matter rolls downhill,” Near said. “Every impact on the headwaters of Little Blue Creek will have impacts downstream.”

Given what is known about data center construction and operations, Near said, those impacts could include increased turbidity from construction and thermal pollution—an increase in the temperature of the stream that could completely extirpate the population of darters the researchers have now documented in Little Blue Creek.

In a previous interview with Inside Climate News, Near said the data center’s construction would “nuke” Little Blue Creek. “My assessment remains the same,” he said Monday. “And now it’s bolstered by the validation that the species indeed occurs in the creek.”

It’s also possible, Near said, that construction of the data center campus, slated to include 18 buildings, each the size of a Walmart Supercenter, could also put species like the watercress darter, already listed as endangered under federal law, at risk. Part of that risk comes from the possibility that developers may “dewater” aquifers beneath the site in order to level and stabilize the land for construction, Near said.

There’s a lot we don’t know about the data center, Near added, given the lack of transparency from developers and public officials alike. Bessemer’s mayor and city attorney, as well as at least one taxpayer-funded economic development staffer, have signed non-disclosure agreements related to the project.

“It’s shocking,” Near said. “I never fathomed a public servant could be beholden to a non-disclosure agreement. It’s just distasteful.”

Near said he accepts that there are cases where development that “improves the human condition” can be put ahead of the goal of preserving biodiversity: “This just doesn’t seem to be one of those cases.”

The Center for Biological Diversity’s petition requesting endangered status for the Birmingham darter is based in part on Near’s findings and on Inside Climate News’ reporting. The fish currently lacks protection because it has only been identified as a distinct species in the last few years.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowWill Harlan, Southeast director for the nonprofit, said that listing the fish as endangered under federal law is critical to preventing the darter’s extinction.

“These phenomenal fish will slide further toward extinction if this data center is built, so

we have to act fast,” Harlan said. “They’ve been swimming in these creeks for millions of years, but without immediate protections, they’ll disappear forever.”

The petition outlines the threats to the darter, including the proposed data center, and also points to a 2025 draft assessment by Alabama officials placing the Birmingham darter in its P1 category of “highest conservation concern,” meaning the fish is “critically imperiled and at risk of extinction or extirpation.”

Charles Miller, policy director at the Alabama Rivers Alliance, a statewide environmental organization, said it’s unfortunate that a newly identified species like the darter is already facing a threat to its existence.

“The fact that this and several other rare darter species found only in Alabama, were first described this year is a stark reminder that we are still uncovering the depth of world-class aquatic biodiversity in our state,” he said. “Protecting this irreplicable natural legacy will benefit Alabamians for far longer than allowing out-of-state developers to make a quick buck.”

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service did not respond to a request for comment on the petition.

A Road to Nowhere?

In a Nov. 4 letter to data center developer Brad Kaaber, ALDOT Director John Cooper said the data center project “appears to conflict with the planned alignment and interchange location for the Birmingham North Beltline and its connection to Interstate 459.”

Cooper said in the letter that ALDOT recognized the data center project “represents a major opportunity” for new jobs and tax revenue and believes the two projects could coexist if modifications were made.

“While proceeding with development on this site as proposed would create serious challenges for the eventual construction of the Beltline interchange, we believe your development can be planned in such a way as not to conflict with the Beltline,” Cooper wrote.

ALDOT also sent copies of the letter to several local and county officials and the text was widely circulated on social media.

A spokesman for ALDOT confirmed the authenticity of the letter, but said the department had no additional comment on whether it had begun discussions with the developers or whether ALDOT could or would stop the data center project if the conflicts could not be resolved.

The Birmingham Northern Beltline is a planned 52-mile semicircle through sparsely populated areas north and west of Birmingham. The project has been in the planning phase since the 1990s and has generated much controversy from people who call it a massively expensive “road to nowhere” that will do little to solve the area’s most pressing traffic problems.

The highway will also carry a huge environmental cost. The beltline, as currently designed, will cut through huge swaths of hilly, undeveloped forest land, including dozens of river or stream crossings. The first segment involved cutting through a forested hilltop and building massive bridge pilings over stream banks below.

“The entire beltline is 52 miles, and it’s going through some of the most scenic, beautiful mountains in Alabama,” Sarah Stokes, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, said last year. “It is going to destroy over 3,000 football fields worth of forest and cross and permanently alter the Black Warrior and Cahaba River tributaries in 90 different places.”

The Birmingham area relies on those rivers for its drinking water, and environmental advocates say the woodlands surrounding the streams provide natural filtration for the city’s drinking water, as well as providing habitat for numerous endangered species.

The Project Marvel data center, a $14.5 billion project according to developers, would likely be completed decades before the Northern Beltline reached it, if at all. The beltline construction began in the northeast segment of the route and will wrap around counter-clockwise toward the Bessemer data center, slated to be located at its western endpoint.

Miller said that ultimately, both the data center and the Northern Beltline pose serious risks to the environment. The difference, he said, is simply their vastly different timelines.

“The lower Valley Creek watershed was already facing a threat decades in the future from the Northern Beltline, but this hyperscale data center poses an imminent threat to the Birmingham darter population in Little Blue Creek,” he said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,