Lea este artículo en español.

MOCOA, Colombia—This isn’t the first time foreigners have shown up here, where the Andes Mountains meet the Amazon rainforest, insisting they needed what was under the ground.

First it was gold, recalled Zuly Rivera, a youth coordinator for the Nasa pueblo, one of several Indigenous groups that inhabit this densely forested region of southwestern Colombia. Then, it was oil. Now, as civilization’s appetite for energy evolves, a Canadian startup is prospecting for copper.

Advocates for copper mining here promise economic advancement, a new generation of responsible industry and a global transition to cleaner forms of power. But Rivera, who has stern eyes and long, black hair, senses a familiar story that is centuries old.

“They come to rob us,” she said. “For more than 500 years they have robbed us and today they continue.”

The daughter of social leaders and an administrator for her community’s territorial defense unit, Rivera is part of an activist network called Guardians of Andino-Amazonia that wants to prevent the development of a mine in the mountains above Mocoa, a small Colombian city surrounded by Indigenous reservations.

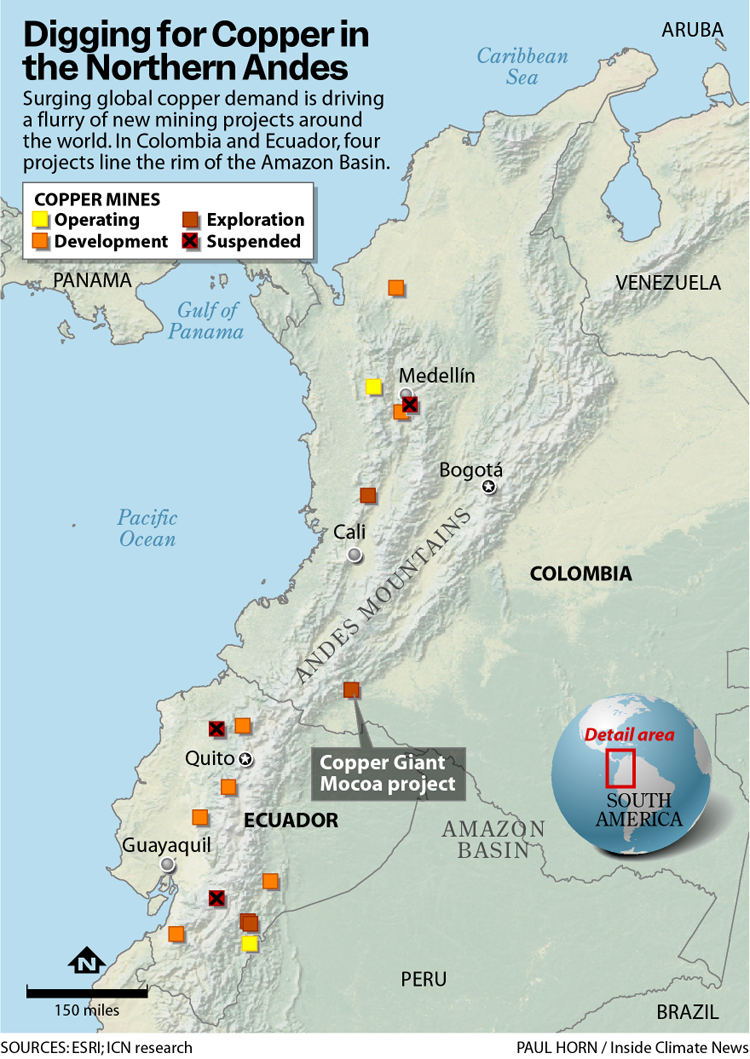

The Mocoa project by Vancouver-based Copper Giant, still in an early stage of exploration, is one of hundreds of potential copper mines advancing worldwide as part of a global rush to dig up metals for electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar farms and the data centers powering artificial intelligence. Most of these projects affect lands of Indigenous peoples, research shows.

Far from Mocoa, throughout the Andes of Colombia and Ecuador, almost a dozen copper projects are in exploration or development, including three on the western edge of the Amazon Basin, where an accident or disaster could spill mine waste into one of the world’s most important and threatened ecosystems.

In the far eastern Amazon, more than 2,000 miles away, Indigenous protesters stormed into the 30th United Nations conference on climate change last week in the Brazilian city of Belém, decrying the ongoing destruction of Amazonian lands. World leaders are gathered there through Friday, considering what to do about a dangerously warming planet. Decades of discussions haven’t stopped the growth of global fossil fuel production or carbon emissions.

Now, amid surging energy demand from wealthy nations, the material needs of technologies meant to replace fossil fuels are fomenting their own wave of environmental threats.

Rivera, 34, gazed from a muddy ridge across the valley where Mocoa, founded in 1551, sits beside its namesake river, nestled between green, misty slopes. It’s not the copper she cares about losing, Rivera said. It’s the spirit of this place. She worries new roads through the jungle, new money in politics and an influx of new residents will eventually transform Mocoa from a secluded enclave of Indigenous cultures into a busy mining town.

“People from outside don’t know the value this has,” she said, waving her hand across the landscape. “For them, it is just a mountain.”

Surging Demand for Copper

Similar tensions are mounting around the world. A Norwegian copper mine in the Arctic faces opposition from Sami herders, and in western Canada the Tahltan Nation has denounced its exclusion from planning for two copper projects in its territory. A copper mine expansion in the Democratic Republic of Congo led to forced eviction of local villages and police crackdowns on protesters, while the U.S. Supreme Court, in October, cleared the way for an Arizona copper mine that will destroy sites sacred to the Apache.

These projects are fueled by billions of dollars from investors and governments aimed at producing materials for high tech manufacturing, and they want copper more than any other metal.

Copper forms the core of electric motors and turbine generators. It makes electrical cables, wires and circuit board pathways. A large solar farm uses hundreds of tons, according to the Copper Development Association, an industry group. A large data center for artificial intelligence uses tens of thousands of tons.

Demand for copper is expected to surge by 24 percent over the next decade, said the market intelligence firm Wood Mackenzie in an October report. Getting there will require building dozens of new mines at a breakneck pace.

“Copper, they say, is the next petroleum,” said Thyana Alvarez, Colombia vice president of Copper Giant, owner of the Mocoa project.

Alvarez, the daughter of a mine engineer, knows about this region’s bad experience with petroleum. Since the 1970s, oil companies have brought outsiders, pollution, deforestation and paramilitary violence with unrealized promises of community development.

Copper doesn’t have to be this way, Alvarez said. It presents “an opportunity to not repeat the errors that others committed.”

For the last four years, Copper Giant has donated to schools, churches, sports teams, communities and colleges in Mocoa and beyond trying to foster a consensus around the project, Alvarez said. The company is building a highway bridge over the Mocoa River, a smaller bridge at a rural community inside its claims and a new road for heavy vehicles between them. Copper Giant is committed to best practices of environmental stewardship and hiring locals, Alvarez said.

The company, however, can’t speak to specifics of a potential mine, still years away. Copper Giant is just an exploration firm—an investor-funded enterprise that acquires and develops mineral reserves with hopes of selling them to a much larger mining company. So, Alvarez can’t say if it would be a surface mine that scrapes away landscapes, or an underground mine that taps deposits through shafts. It would probably be an underground mine, she said.

“A New Chapter”

Copper has stirred excitement in Colombian business and politics. Alvarez, whose father worked his career at the country’s largest coal mine, was named one of Colombia’s most influential women of 2025 by Semana magazine for her leadership in emerging industries and the energy transition.

Currently Colombia’s top exports are oil, coal and black-market cocaine. But the metallic deposits in its Andes Mountains formed in the same way as deposits in the Andes of Chile, the world’s top copper mining country, suggesting high production potential.

“We are opening a new chapter,” Álvaro Pardo, head of Colombia’s National Mining Agency, told the market intelligence service ChemAnalyst at a conference in March, where he announced auctions of 17 new copper leases. “It’s about securing our infrastructure, powering our green energy transition, and establishing Colombia as a self-sufficient copper producer.”

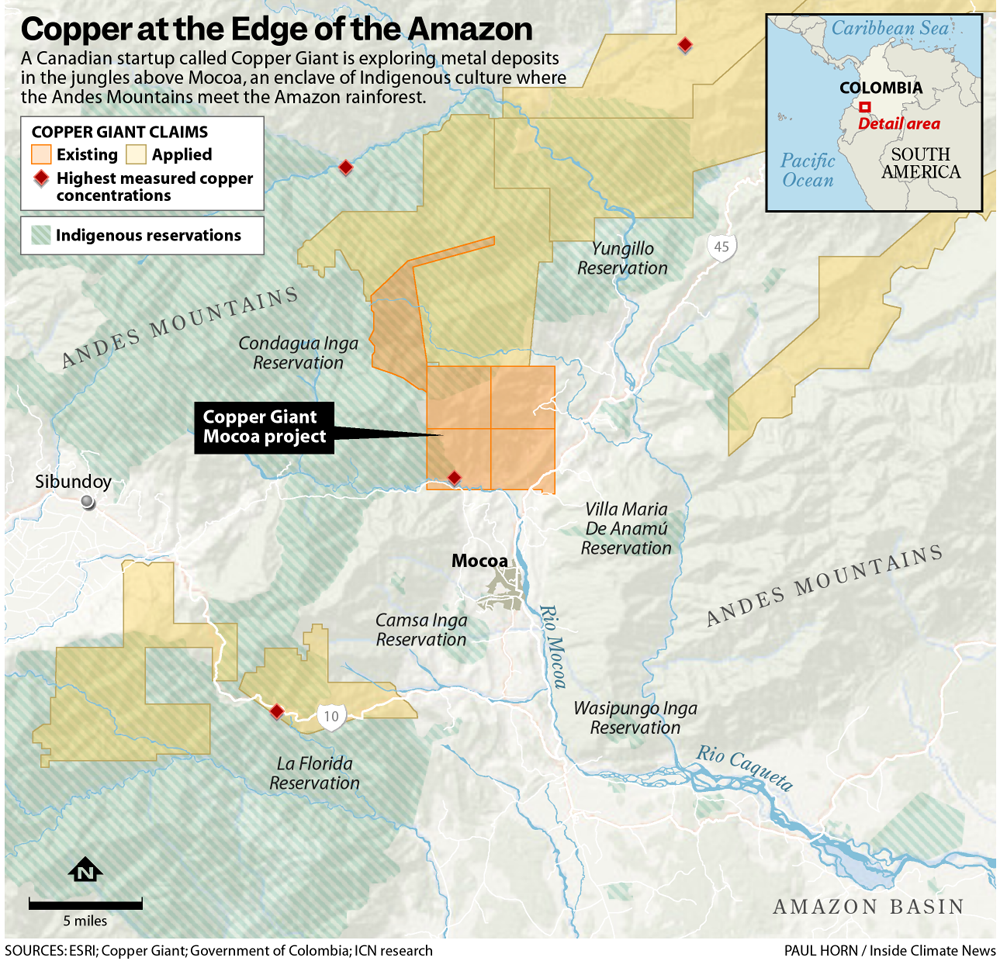

In the mountains above Mocoa, Copper Giant studies from 2022 estimate the company’s claims held 2.3 million tons of copper—enough to run high-power industrial wires around the Earth 96 times. This year, Copper Giant changed its name, previously Libero Cobre, to reflect its “belief that Mocoa is not simply a deposit, but potentially part of a much larger, district-scale copper system,” an announcement said. Two months later it expanded its mining claims by 64 percent to span nearly 340,000 acres.

“We’re building the technical foundation for the next phase of Mocoa’s growth,” said Copper Giant CEO Ian Harris in a press release last month.

The buzz has made locals nervous. The environmental group Guardians of Andino-Amazonia, founded in 2022, has organized festivals, hosted forums, visited schools and produced theater performances to raise awareness about what’s at stake if mining commences in the mountains where several rivers originate.

“People need to know more,” said Sirley Cely, a member of the group and Mocoa chapter vice president of Colombia’s Community Action Boards, a national civic organization. “The copper will go to sustain the lifestyles of the Northern countries, as always, but at the cost of wellbeing in the Southern countries.”

Cely, 43, lives 15 minutes outside Mocoa’s urban center, down a muddy road in a forested hamlet with five wooden houses surrounded by palm thickets, native fruits, giant ferns and mossy trees that twinkle with colorful birds. She planted many of these, she said, strolling barefoot through her wild garden.

Families around here depend on tourism, she said. Eco-lodges host foreign visitors, while shops and restaurants along the nearby river cater to residents of Mocoa, who flock here on weekends to bathe in clean water from the mountains.

If copper’s potential is as big as the businessmen insist, Cely worries what it means for this place in the Amazonian highlands.

“The culture of our territory would change,” she said as tamarin monkeys chirped in the canopy above her house and a pig napped on the porch. “We’d end up being a mining city.”

The Energy Transition and Indigenous Land

Thousands of projects like Mocoa are advancing globally. Most are located on or near the lands of Indigenous people or small, traditional farmers, according to a study published in 2022 in the journal Nature Sustainability.

The study tallied 5,097 projects to mine metals for the energy transition, including more than 1,500 operating mines and almost 3,600 in development. More projects targeted copper than any other metal. The study said almost 70 percent of operating and proposed copper mines, about 1,400 projects, sit on or near Indigenous territory.

Around Mocoa, Copper Giant’s claims include several sacred sites, according to a statement issued by seven local Indigenous organizations this year.

“There can be no energy transition or real sustainability if it is based on the destruction of sacred territories,” it said. “This is not just an Indigenous struggle: it is an ethical and urgent call for the survival of life on Earth.”

Copper Giant’s claims also include parts of three reservations that belong to Inga groups, the most populous Indigenous ethnicity around Mocoa. In October, Copper Giant announced the conclusion of negotiations with the Condagua Inga reservation and adoption of an agreement “to protect cultural identity, strengthen local capacities, and ensure that development in Mocoa advances in balance with nature.”

But the impacts of a mine would reach farther than the reservations within its claims, said Ingry Paola Mojanajinsoy Buesaquillo, chair of the association of Inga councils in the city of Villagarzón, 10 miles downriver from Mocoa. Everyone who relies on the rivers that flow from those mountains, she said, should worry.

“The copper project affects us all,” Mojanajinsoy said, speaking in a garden of the association’s headquarters. “They are above and we are below.”

Communities will wither without their water sources, she said. She’s seen it happen thanks to oil drilling. This week she’s in Brazil, at the U.N. conference on climate change, asking leaders to stop the advance of oil companies in her territory, as well as the copper mines that are supposed to replace them.

“Do the energy transition without sacrificing Indigenous territory,” she said. “Otherwise it’s going from one bad thing to another.”

Waste and Other Risks

The biggest environmental risks of mining operations stem from their enormous volumes of waste. Mine operators crush millions of tons of rock, mix it with fluids, extract small concentrations of desired metals, then discard the sludge, called tailings. To contain tailings, companies build pits, dams and other impoundment structures, which periodically fail.

For example, this year in Zambia, a dam on a tailings reservoir broke at a copper mine, spilling the toxic sludge into the country’s main river. In Brazil, a tailings dam collapse in 2019 flattened nearby villages and killed 270 people. Another Brazilian tailings dam failed in 2015, spreading pollutants along more than 400 miles of waterways. Tailings dams collapsed in 2014 at copper mines in Mexico and Canada, contaminating water sources of Indigenous communities.

Mine waste contains natural minerals that may be harmful. Studies of tailings from Andean copper deposits in Chile found arsenic and cadmium, which cause cancer, as well as lead and other heavy metals. The tailings also contain sulfide minerals like pyrite, which transform into acid when exposed to air and water, dissolving rocks, carving pathways and creating runoff.

Other studies in Chile have identified tailings contaminants in farm soils several kilometers from a copper mine, and in the air of Indigenous villages some 50 kilometers (about 30 miles) away. The city of Calama, known as Chile’s copper capital, has lung cancer rates almost three times the national average.

Natural disasters can also destabilize mines. This year, earthquakes caused a deadly collapse at a copper mine in Chile and flooding at a copper mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo. A landslide in September killed seven workers at an Indonesian copper mine. Mocoa suffered a catastrophic landslide in 2017 that killed more than 300 people and left many locals wary of plans to mine in the mountains.

“Mining is a risky activity,” said Oscar Jaime Restrepo Baena, a mine engineer and professor at the National University of Colombia’s school of mines in Medellin. “It must be done well and it must be done responsibly.”

Colombia lacks experience with mining or comprehensive mining policy, he said. But with the right balance of foreign technical expertise and local community involvement, he believes Colombia can develop a clean, safe mining sector.

He said the Mocoa project has “enormous potential,” and that Copper Giant has conducted notable public outreach to win local support.

“Communities are right to have fears, and companies have an obligation to address them,” Restrepo said. “Trust isn’t given overnight. Trust must be earned.”

Oil’s Dirty Legacy

Mojanajinsoy does not trust the company. For her, mining disasters are easy to imagine. Despite promises of a clean energy revolution, her expectations for copper come from her experience with oil.

Spills have become part of life since oil companies arrived decades ago, she said. The largest in recent memory happened just over a year ago at a site owned by Canadian driller Gran Tierra on the Wasipungo Inga reservation, a 1,780-acre forested preserve where Mojanajinsoy lives with her two daughters and hundreds of other Inga families.

It left oil in the creek for eight months, she said.

“The rivers have suffered,” Mojanajinsoy said. “After they are contaminated, they don’t go back.”

Local news websites ran a press release from Gran Tierra that blamed vandals for opening the valves of eight tanker trucks. In a statement to Inside Climate News, a Gran Tierra spokesperson said the company led and paid for cleanup after the spill, and that it continues to support local authorities investigating who was responsible.

“We believe that responsible energy development should generate long-term value for people, communities, and the country,” said the spokesperson, Nicolas Barrios Rubio. “Gran Tierra Energy is committed to protecting freshwater resources in Colombia.”

Water pollution isn’t the worst of Mojanajinsoy’s fears. Beyond environmental destruction, oil drilling brought cultural destruction of Indigenous people as the flood of wildcatters, money and development gradually pushed the Inga and others to the periphery of their own lands.

“Territory is everything, for the culture to continue, for new generations,” Mojanajinsoy said. “Culture gets lost with the territory.”

Over the years, companies continued to show up bearing titles to lands of local peoples. Resisters faced the brutal private security groups that protect company interests.

“If you talk, they will kill you,” said Matias Redri, a Murui pueblo elder who lives near Mocoa. “Whoever has money makes the rules.”

Even where territory remains, it changes. Indigenous cultures only exist within their environment, like an ancient tapestry woven between every spirit, emotion and object of the forest. As bits of their surroundings fall away, the stitches in their culture begin to come loose.

“We are losing,” Redri said.

Roaring machines, glowing gas flares and the spread of deforestation scare away the animals. Pollution saps the vitality of ecosystems. To each new generation, the stories and customs of their ancestors make less and less sense.

“We’re in an unstoppable loss of that ancestral knowledge,” said Carlos Fernandez, a local representative of the international nonprofit Amazon Watch. “Many of the pueblos are in danger of cultural extinction.”

An “Important Step”

Miguel Vargas Vidal, an ethnic liaison for Copper Giant in Mocoa, understands why people are suspicious. He also experienced the problems of oil drilling here. A member of the Guitoto Murui pueblo, he lives with his Inga wife on a reservation.

Vargas visits rural communities in the areas of Copper Giant’s exploration activities to learn about their needs, explain the project and build trust with the company. He reminds them Copper Giant isn’t a mining company, only an exploration company. Copper will not be a repeat of oil, he insists.

“We should learn from those errors,” he said. “We don’t have to be afraid.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowDevelopment for Indigenous people doesn’t mean building roads and stores, he said. It means fortifying culture. That’s why Copper Giant works through the traditional social structures to provide in-kind support for customary activities, like communal work days, Vargas said. The company also sponsors traditional carnivals for the communities.

In October, when Copper Giant announced its agreement with the Condagua Inga reservation, it laid out six initiatives to protect cultural identity, preserve the Inga language, acknowledge traditional ecological wisdom and safeguard local water sources.

Vargas said environmentalists have spun up dramatic scenarios to spread fear about the copper project: that it will collapse the mountain, that it will contaminate the water, that its riches will go to foreign countries. He asked how they can make such specific predictions about a mine plan that doesn’t exist yet?

“The unknown always generates fear,” he said. “We’re making sure this is done well.”

It’s not just a local opportunity, he said, but a calling to contribute to humanity. The world needs copper if it wants to replace the vehicles and power plants that burn fossil fuels. Colombia has copper to offer. It would be selfish not to contribute, Vargas said.

“It’s clean energy. This is the 21st century,” he said. “We have to take this important step.”

An Older Kind of Wealth Lost in the Process

Rivera, the youth coordinator for the Nasa pueblo in southwestern Colombia’s dense forest, still wonders if the energy transition is a step forward for Mocoa, or just more business as usual. She has heard about the energy transition for years at regional summits and U.N. conferences on climate and the environment. Meanwhile, she said, the conditions of Indigenous peoples here have only continued to worsen. She’s never seen an electric vehicle in Mocoa.

“We aren’t interested in your flying cars and robots in Europe and Asia if all the minerals come from South America,” she said.

She doubts that anyone actually needs this copper. Europeans needed gold, but what they took only sits in dark vaults. Gold mining continues to menace the Amazon. North Americans needed oil, then they burnt what they took and now, apparently as a result, they need copper. And they still need oil.

If this is a transition away from fossil fuels, will the drillers leave? Or will the mine settle in beside them as one more hazard eating away the most vibrant ecosystems and oldest cultures on earth, Rivera asked.

She knows people are tempted by the treasures foreigners bring, and she understands the struggles with poverty. She learned about her community as a child trailing her mother, a teacher, and her father, governor of their territory. Now she gives seminars to help Indigenous youth understand they aren’t as poor as they often are told.

“We aren’t interested in your flying cars and robots in Europe and Asia if all the minerals come from South America.”

— Zuly Rivera, Nasa pueblo youth coordinator

They also have wealth and inheritance: the knowledge of fish, fruits, medicines and spirits of the forest, which their cultures acquired over ages; the unspoiled places their ancestors left them; the mystical beauty that nourishes and makes them happy. “All of that is part of our riches,” she said.

The outsiders don’t see it. They trample it digging up their own riches, which they ship to their countries, leaving the social fabric of local communities disfigured.

Whatever wealth the communities acquire, Rivera said, comes at the cost of an older wealth that gets stolen and forgotten.

“They think riches are about having so many cars,” she said. “I think riches are being able to live and enjoy the water.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,