I’m biking down Logan Boulevard on a bright Chicago morning. Tall maples filter the sun into dancing patches of shade. Joggers pass, dogs tug at leashes and parents steer strollers along broad sidewalks buffered from traffic by wide medians. The air feels calm and clean, almost like a park pretending to be a street.

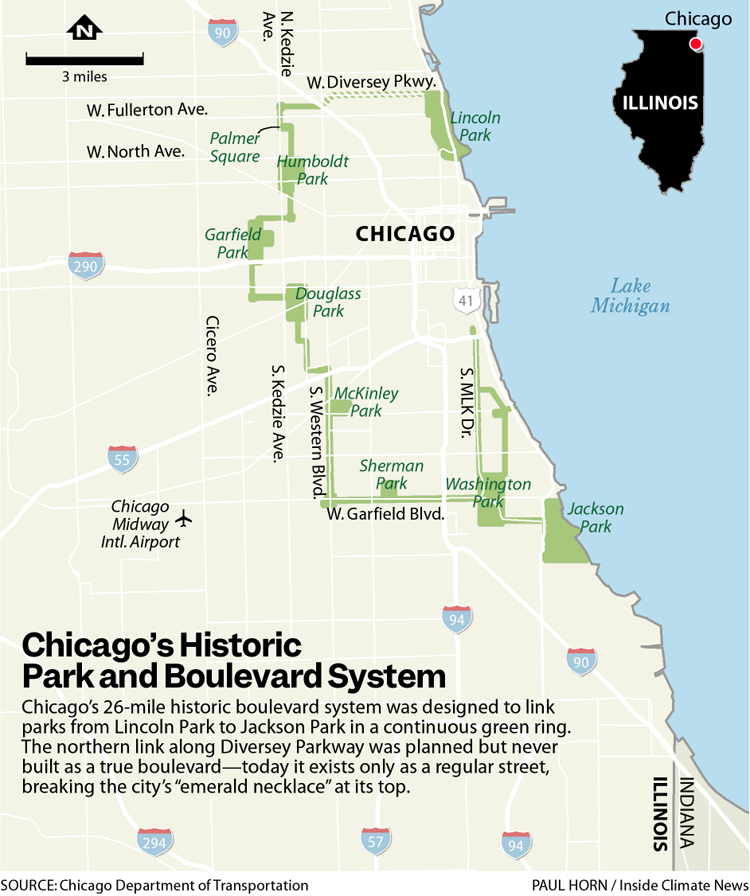

Logan Boulevard is the northern entrance to Chicago’s historic park and boulevard system. This network stretches 26 miles and connects parks and squares across 23 community areas. It’s a living artery of trees and lawns meant to connect neighborhoods and cool the streets. The plants help reduce flooding, too.

But a few miles south, the shade disappears. Puddles replace grass, and the sound of cars drowns out the birds. Cracked sidewalks mark where investment stopped. The same system built to unite Chicago now exposes its divides—between shaded, well-funded Logan Square and neglected stretches like Western Boulevard.

According to data from weather-information provider Meteostat, Chicago is seeing more sweltering days each year. In 2023, the city had nine days with average temperatures above 81 degrees Fahrenheit. That nearly doubled to 16 in 2024—and surged to 29 in 2025, the most in recent years. Rainfall is intensifying, too. Last year, Meteostat figures show, rainstorms dumped about 10 billion more gallons of water on Chicago than in the year before.

As summers grow hotter and storms hit harder, these boulevards could become the city’s first line of defense. I set out to ride their full length to see how climate stress and social inequity intersect along Chicago’s green spine.

After Logan Boulevard, past Logan Square Park and down Kedzie Boulevard, I reach Palmer Square Park. The first thing that strikes me is the trees—more than 150 of them, across 28 species, from red maple and serviceberry to bur oak. The ArbNet Arboretum Accreditation Program accredited the park as the first arboretum in Chicago.

It’s shaded and dry, with two open lawns for play and sports. Joggers circle the path, readers occupy benches and children climb the playground. The surrounding streets are narrow, with frequent stop signs that make the park easy to reach.

It wasn’t always like this.

“When I moved here in 1978, the park was mostly dry clay,” said Steve Hier, a board member of the Palmer Square Park Council. “That caused flooding.” At the time, the neighborhood was deemed unsafe and homes were cheap, but the architecture drew new residents. “People moved for the cheap and beautiful homes—and decided to make it a beautiful place.”

Through the homeowners’ association, residents took matters into their own hands. They dug, planted and raised money for trees. Neighbors volunteered to water them through that first summer. The city didn’t help, Hier said.

“It’s up to the community,” he said. “People complain, but if you don’t get together and go to meetings and sign petitions, nothing will happen.”

Palmer Square Park shows what local ownership can do. Its trees cool the air and soak up stormwater before it floods the streets. But community stewardship works best where people have resources—time to volunteer and money to spend. The median household income around Palmer Square is over $100,000, compared with about $75,000 citywide.

Three miles south, in Garfield Park, the story changes. The median household makes less than $40,000, yet the park and the boulevards around it—Franklin and Central Park—are well maintained. A natural area of trees and native plants stretches along the lagoon. People sit in the shade, reading or talking, while others jog or walk by the water.

Most rainwater flows into the lagoon, or the native plants’ deep roots absorb it, keeping the soil loose and breathable. Some flooding still happens on the east side near Sacramento Boulevard.

Mike Tomas, executive director of the Garfield Park Community Council, said the council received help from the city and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago. The council is creating an orchard at 5th Avenue and Sacramento Boulevard, green infrastructure to manage stormwater and build community ties.

“We’re using green efforts to get residents involved,” Tomas says. “Farmers’ markets, community gardens, the orchard—all of these bring people out and give them a say in shaping their neighborhood.”

Projects like this show what’s possible when public investment meets local commitment. But as I keep biking south, that balance begins to fade.

On Western Boulevard, the trees, medians and sidewalks tell a very different story. Eight lanes of traffic roar past—four for the boulevard and four for Western Avenue. The noise is constant, the air thick. The sidewalks have cracks, and the median path is broken and uneven. A few scattered trees throw patches of shade, but flooding pools between shallow drains.

I biked the three-mile stretch and saw only one other person using the green space. Most people avoid it. There are almost no crosswalks, and traffic separation is unclear. It feels built for vehicles, not people. The area is industrial—warehouses, parking lots and trucks dominate the landscape. Homes are mostly at the ends of the boulevard or tucked behind businesses. The city maintains the streets for freight, not recreation, a problem for access and safety.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe trees that line the median could cool the air and absorb stormwater, but they’re trapped behind lanes of speeding traffic. “We have to ask if we really need that many lanes,” said Rogelio Cadena, visiting assistant professor at the Illinois Institute of Technology College of Architecture and cofounder of design firm Resolver Studio. “Western Boulevard is an industrial corridor.”

Cadena believes events and design interventions can bring people back to these spaces.

“Through public events, we can draw attention to the boulevards and rethink their purpose,” he said. “That can also bring the community together.”

He helped coordinate two events: Piñatas on the Boulevard at Western and the Sukkah Design Festival on Douglas Boulevard. These temporary installations invited residents to gather, talk and dream up new uses for public spaces.

The next step is collaboration. This means connecting neighbors, city agencies and designers. Together, Cadena hopes, they will restore function and build community ownership. “But we need to be more conscious,” he added.

As I bike back north, I think about how success can bring new challenges. Logan Square might have the healthiest boulevards and parks, but it’s also one of the most gentrified neighborhoods in Chicago.

Winifred Curran, a geography and GIS professor at DePaul University in Chicago, warns about green gentrification. “We need to be cautious,” she said. “Making environmental improvements can raise property values and displace long-term residents in neighborhoods that have faced years of disinvestment.”

Keeping housing affordable, she added, is critical if climate resilience is to benefit everyone. “The city could sell vacant lots at low prices to nonprofits or impose a property tax freeze on landowners,” she said. “Rent control has worked in many European cities but remains unpopular in the U.S.”

Biking the length of Chicago’s boulevard system reveals how climate and inequality intertwine on every stretch of road. Some neighborhoods cool under dense shade; others bake on cracked concrete. Yet the idea behind the boulevards still holds power—a continuous green network meant to connect people and protect the city from heat and floods.

The future of that promise depends on Chicago’s investments. It’s not just about trees and drains; it’s also about the people living along this green spine. The boulevards connect the city, tree by tree and block by block. They remind Chicago that resilience grows in community as much as in soil.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,