RICHMOND, Calif.—On a sunny morning in May, Luna Angulo walked alongside a towering chain-link fence topped with razor wire on San Francisco Bay’s eastern shore. She lingered near locked gates posted with warnings to keep out of the “hazardous substance area,” where long-shuttered chemical plants had dumped toxic waste on marshlands, and recounted the refinery explosion that changed her life.

Angulo was just 12 years old when a massive explosion rocked Chevron’s accident-prone Richmond refinery, four miles up the road. Towering clouds of black smoke darkened the skies for hours that summer day in 2012, forcing 15,000 residents to seek medical care for chest pain, headaches and asthma, among other ailments.

The catastrophic fire haunts the collective memory of this working-class town, where industrial accidents regularly plague largely Black and Latino neighborhoods surrounded by polluting railroads, deepwater ports and freeways. It also turned a generation of young people into climate activists.

“That fire was a big catalyst for a lot of us,” said Angulo, now 25, who co-founded the climate justice group led by gender-queer activists called Rich City Rays and organizes non-violent protests against Chevron, the second-largest greenhouse gas emitter in California.

Angulo, a first-generation Mexican-American, grew up with asthma. But she didn’t connect her breathing problems to Richmond’s rampant pollution until the refinery fire left so many gasping for air. Now she sees the oil-storage tanks blanketing the hills beyond her mother’s kitchen window as “symbols of harm along the hillside.”

And experts worry that the health costs of living in a heavily polluted city could reverberate for generations if little is done to curb heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions. That’s because surging seas will increase flood risks for hazardous sites in Richmond and other overburdened cities along U.S. coasts, scientists at the University of California, China’s Nanjing University and Climate Central, a nonprofit science organization, warn in a study published Thursday in the journal Nature Communications.

Low-income neighborhoods and communities of color face a disproportionate share of the risk, they found.

Rachel Morello-Frosch, an environmental-health disparities expert at the University of California, Berkeley, and co-author on the study, has spent the past several years evaluating climate pollution’s likely impacts on low-lying industrial regions and vulnerable populations.

Burning fossil fuels makes flooding not only more destructive, by destabilizing the climate and supercharging waves, storms and high tides, but also more dangerous, by releasing toxic substances like petroleum and untreated sewage in the path of roiling floodwaters.

Morello-Frosch worries that toxic floodwaters are more likely to imperil low-income communities of color like Richmond because decades of discriminatory housing, lending and employment practices have left residents stuck living near polluting industries without the means to mitigate harm when disaster strikes.

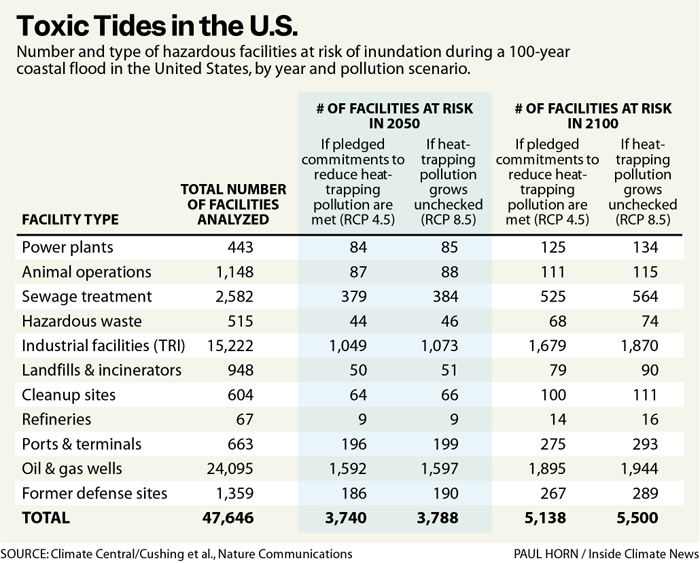

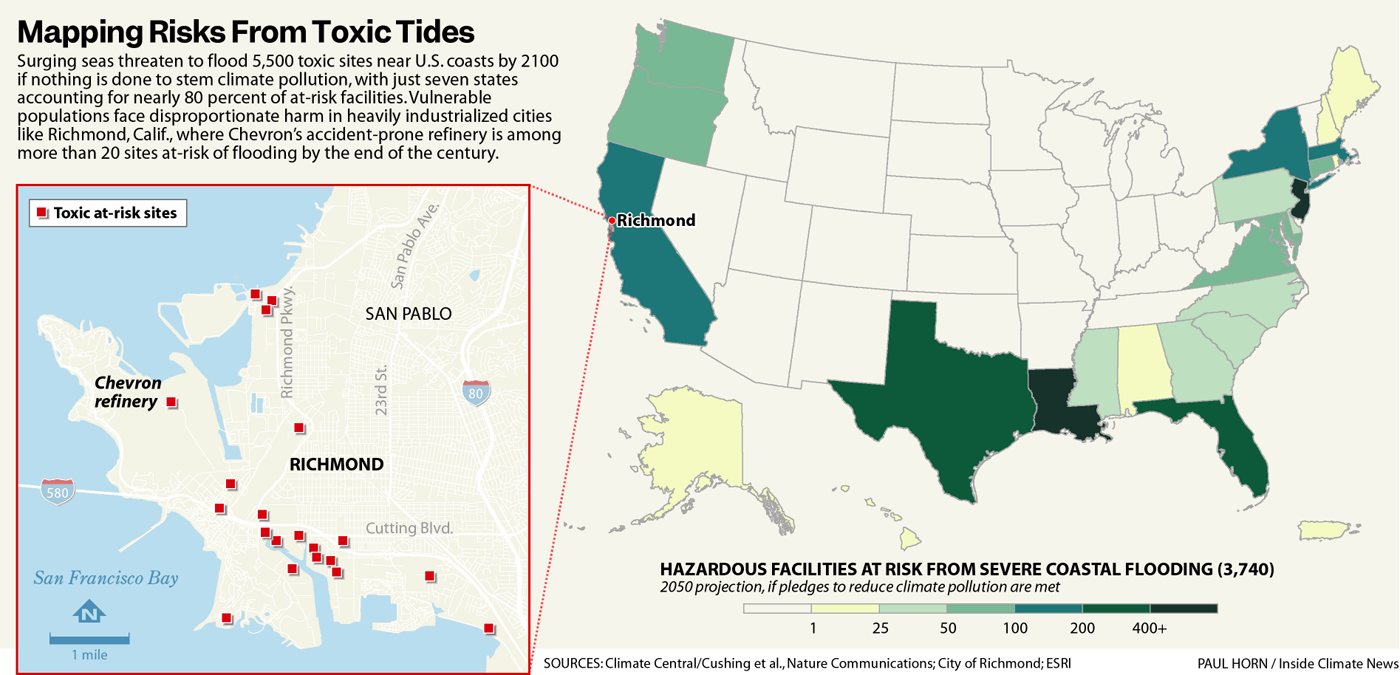

To help communities and policymakers prepare for future threats, the research team conducted the first national assessment of unequal risks from flooded hazardous sites related to sea level rise. Of nearly 48,000 U.S. facilities that store, handle, produce or release harmful substances, they identified 5,500 that are likely to experience a 1-in-100-year flood event—that is, an uncommonly large flood that has a 1 percent chance of happening in any year—by 2100. Nearly 3,800 sites are likely to flood by 2050.

Curbing emissions would spare a few hundred sites by 2100, the team found. But past climate pollution has “locked in” projected flood risks over the short term.

“Over 5,000 facilities are projected to be at risk of a 1-in-100-year flooding event in 2100 if we don’t do anything, and we just learned that we’re failing to meet the 1.5 degree Celsius benchmark,” said Morello-Frosch, referring to the Paris Agreement target to avoid potentially irreversible effects of climate change.

About two dozen coastal states plus Puerto Rico are likely to see at least some hazardous facilities flood. But the vast majority of at-risk facilities are concentrated in just seven states. Topping the list is Louisiana, with its dense concentration of oil and gas wells, followed by Florida, New Jersey, Texas, California, New York and Massachusetts.

Oil and gas wells and industrial facilities that emit toxic chemicals tracked by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxics Release Inventory together make up nearly 70 percent of sites likely to flood by century’s end. Other facilities include sewage treatment plants; ports and terminals that import, export and store fossil fuels; former defense sites; and power plants.

Exposure to toxic substances like pathogen-laden raw sewage, industrial chemicals and hydrocarbons has been linked to numerous short- and long-term health conditions, including heart problems, cancer and respiratory, gastrointestinal and skin conditions, risks that can persist for residents and clean-up workers long after floodwaters recede.

Overburdened communities like Richmond, where poverty and other social stressors exacerbate environmental exposures, are 50 percent more likely to be within a kilometer (0.6 miles) of a hazardous site at risk of flooding by century’s end, the new study found. Hispanic residents, single parents, nonvoters, renters, people over 65, and those in poverty, without access to a vehicle or with limited English skills are up to 41 percent more likely to live near an at-risk site.

“Ideally we would have a federal government that was enabling communities to plan and respond and proactively address these risks,” Morello-Frosch said. “But right now, these states are left to their own devices,” she said, referring to the Trump administration’s massive cuts to federal disaster relief and related programs.

And as it becomes increasingly difficult to access federal resources and data, including datasets used in this study, she said, states are going to have a harder time addressing future threats.

“A Legacy of State-Sponsored Racism”

Angulo studied a map showing nearly two dozen hazardous sites likely to flood in her hometown: Superfund and cleanup sites like the one at the marsh, fossil fuel ports, chemical manufacturers, a sewage treatment plant and the Chevron refinery, which emitted most of the 812,000 pounds of toxic chemicals, heavy metals and carcinogens released last year by Richmond’s industrial facilities.

An elementary school, Peres K-8, where children play downwind of the refinery next to a major freeway, lies within a half mile of two chemical plants likely to flood.

“A petroleum pipeline runs right under the sidewalk in front of the school,” Angulo said.

The new study excludes pipelines despite their vulnerability during severe floods, the authors said, because national data on pipeline locations is limited.

Angulo was not surprised to see the concentration of at-risk industrial sites around the Iron Triangle, where less than 10 percent of residents are white, and North Richmond, a small unincorporated community where 96 percent of residents are people of color.

“It’s a legacy of state-sponsored racism and state-sponsored segregation,” Angulo said, referring to federal housing policies that, until passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, considered people of color threats to property values.

Around Richmond, Angulo said, “neighborhoods like North Richmond and the Iron Triangle were historically the only places Black and brown folks were allowed to own houses.”

Even though Black migrants fleeing the Jim Crow South helped Richmond build more warships than any other U.S. shipyard during World War II, they were denied access to government-insured loans and had to resort to makeshift construction materials. “That’s why Parchester Village was built,” she said.

Parchester Village, promoted as a “community for all Americans,” was surrounded by heavy industry and flanked by two railways.

Thomasina Horsley grew up in Parchester Village, where heavy rains inundated the housing tract soon after it was built in 1949. Her mother, Margaret, one of Parchester’s original residents, remembers floodwaters rushing from one end of the neighborhood to the other.

Engineers warned county officials in the 1950s that a “dangerous mixture of oil and water” would pass through Parchester if a storage tank up the hill in the “tank farm” run by Chevron’s predecessor, Standard Oil, were to burst during a storm.

Parchester’s flooding problems were compounded after developers removed a eucalyptus grove on a hill near the old tank farm about five years ago to build million-dollar homes, Horsley said. Without the trees to catch water during heavy rains, she said, “there’s water all over.”

The city is working to fix the problem, just one of many in a city of ever-present dangers.

“We’ve had so many bad things happen, people just go into survival mode,” said Horsley.

Like the time in 1993 when a railroad tank car at a now-defunct chemical company released a miles-long cloud of sulfuric acid over homes, sending 24,000 to local hospitals and leading to a $180 million class-action settlement.

“There’s always these tanks around with something leaking,” Horsley said. “Then we get the downwinds all the time with all these chemicals coming from Chevron. You smell them all the time.”

Living near some of California’s biggest pollution sources has created and exacerbated residents’ health problems.

People who have asthma are more sensitive to chemical emissions, but they’re living near some of the highest emissions while lacking access to healthcare, Angulo said. “It’s just like a triple whammy of harm.”

Both Angulo and her sister grew up with asthma, but their brother, who grew up in Mexico rather than Richmond, did not. Plus, there’s no history of asthma in their family. “It’s a clear signal that growing up here is what did it,” she said.

About 25 percent of Richmond residents have asthma, compared to 13 percent of California residents. Asthma emergency department visits in the Iron Triangle are higher than 99 percent of California census tracts, state data shows.

So many people are already suffering from industry’s noxious releases, Angulo said. How are they supposed to handle even more toxic threats from rising seas when they have nowhere else to go?

“Blatant Neglect”

Doria Robinson, a third-generation Richmond native who serves on the city council, runs a community food project called Urban Tilth in North Richmond. The farm, which hires and trains local residents to support a healthier community, sits half a mile from a sewage plant likely to flood.

Two creeks flank the farm, which regularly saw “massive flooding” until about a decade ago, when the county raised their levees, Robinson said, pointing beyond rows of leafy greens and flowers as roosters crowed behind her.

“But now we’re in a new regime with climate change and storm events that are just unheard of, like atmospheric rivers,” she said, referring to powerful storms that have become even stronger as the world warms. “How many record-breaking storm events can you have in a season that are supposed to come every 100 years?”

Robinson helped the city negotiate a deal in which Chevron agreed to pay Richmond $500 million over the next 10 years instead of tens of millions each year in a “polluters pay” refinery tax.

“For us to have a multinational, multibillion-dollar corporation right here in our backyard with the amount of disinvestment in the community, the amount of deferred investment in our infrastructure, the built environment that makes up this city is just,” Robinson said, pausing to find the right words, “just blatant neglect.”

Chevron is an essential part of Richmond’s and the region’s economy, contributing over $1 billion in economic activity annually, Caitlin Powell, a spokesperson for the Richmond refinery, said in a statement. “Our recent agreement with the city underscores the essential nature of our relationship with the city, and we hope the associated additional funding will be used responsibly and transparently to help our Richmond community flourish.”

Robinson wants the Chevron tax settlement funds to go toward reversing decades of lack of investment. “I strongly believe that we need to focus on these types of threats that are only going to be exacerbated by climate change, and put some resources toward trying to figure out how to get ahead of them,” she said.

She’s particularly worried about how rising seas will affect hazardous waste sites that were “cleaned up” by capping the soil with concrete and asphalt.

When Robinson thinks about sea level rise, she thinks about saltwater pushing groundwater up against those caps, inundating toxic soils and carrying contaminants into old, poorly maintained sewer pipes that run under houses, parks and schools.

“We’ve got an old DDT factory and all these other things where supposedly a cap was gonna save us,” she said. “Our grand plan to use these massive caps is totally undermined by intrusion of water underground.”

Threats From Below

Robinson first heard about the threat of rising coastal groundwater from researchers at UC Berkeley who were not involved in the new study.

Emma Lasky, a doctoral candidate at UC Berkeley, and her Ph.D. advisor, Kristina Hill, study the likelihood that groundwater will rise along with sea level and dislodge contaminants at hazardous sites capped with materials like concrete.

“When we thought of the problem as rain spreading the contaminant through infiltration, it made sense and it sounded cost effective,” said Hill, referring to the concrete cap. “It was like putting an umbrella over the contaminant.”

But now, said Hill, associate professor of landscape architecture and environmental planning at UC Berkeley, “we see that it’s about water rising up from below and even changing flow directions.”

As dense saltwater moves inland, studies show, it slides under and pushes groundwater toward the surface, where it can mobilize contaminants once sequestered in groundwater and soil.

Lasky is looking at how seasonal variability in precipitation affects the concentration and movement of toxics like volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at the contaminated Richmond marsh. Lasky and Hill think VOCs, which can prove harmful even at low levels, may be moving through sewer pipes, which can ferry volatile chemicals thousands of feet, and entering homes through broken toilet seals, shower drains or cracks in home foundations.

To understand how rising waters might affect VOCs, Lasky placed sampling devices on sewer laterals, which connect main sewer lines to buildings, to compare the chemicals’ concentrations during the dry season and after atmospheric rivers, which served as a proxy for sea level rise.

So far Lasky has found a chlorinated VOC linked to several cancers at higher concentrations during the rainy season. The finding suggests that an influx of VOC-tainted water, whether from heavy rains or surging seas, could enter cracks in sewer systems and seep into buildings.

Lasky hasn’t tested for VOCs in homes served by the sewer that runs through the marsh yet. But she’s concerned that, if she finds them, people may not have the money to make repairs. She’s even more concerned that most people don’t even know about the problem.

Lasky and Hill are doing their best to sound the alarm.

Since high tides and heavy rains can raise groundwater enough to mobilize contaminants, Hill said, “the impact of sea level rise is really a game of inches, not of feet.”

And that’s a major concern for coastal sites as contaminated as the Richmond shoreline.

The marsh usually floods with heavy rains, Angulo said. “Baxter Creek runs right through all of this super-toxic land,” she said, pointing beyond the fence posted with “keep out” signs. “All of the rainwater, all the ocean water that flows back up, gets mixed in with all the chemicals in the dirt.”

The creek flows through people’s backyards on the other side of the freeway in a public housing complex. “It’s a majority Black, brown and low-income community, which as we know are the most at-risk when it comes to health impacts,” she said. And now, when bigger and bigger rains come and sea level continues to rise with climate change, she added, they’re sitting on a “ticking time bomb.”

Resilience Denied

As the rate of sea level rise continues to accelerate, scientists expect to see rapid increases in the frequency of flooding from high tides along U.S. coastlines as soon as the next decade.

Still, compared to an extreme weather event like a hurricane, sea level rise is relatively slow-moving, giving states and municipalities time to prepare, said Morello-Frosch.

She hopes agencies use the study results to prioritize resources for communities facing significant threats by doing more site-specific assessments, looking at other hazardous facilities like pipelines, accounting for rising groundwater and supporting more resilience planning.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe results can also help vulnerable communities advocate for incorporating sea level projections into cleanup plans for hazardous sites, she said.

Urban Tilth’s Robinson was trying to address how climate change might multiply the dangers of North Richmond’s industrial hazards when she helped secure a $19 million Community Change Grant from the Biden administration’s EPA.

“The grant was going to be a major investment in an area that has just taken the brunt and carried the burden of fossil fuel impacts for 100 years,” Robinson said.

The North Richmond Resilience Initiative was one of more than 400 grants funded by the Inflation Reduction Act that the Trump administration canceled in March. It would have created green space at the elementary school near the at-risk wastewater treatment plant to filter pollutants from a massive warehouse being built next door. It would have transformed an abandoned public housing project into affordable, energy-efficient homes. It would have created a community disaster response hub at Urban Tilth, among other projects.

When California Reps. John Garamendi and Mark DeSaulnier urged the EPA to reinstate the congressionally mandated appropriations, they were told the initiative funds programs that “promote or take part in DEI or environmental justice,” undercutting the agency’s priority “to eliminate discrimination” in its programs.

The EPA press office did not respond to a request to point out discriminatory programs in the grant.

Robinson was shocked when she saw the EPA’s reason for canceling the grant. The grant was trying to address a long history of compounding threats focusing on the geography of North Richmond, not on specific populations, Robinson said. “It’s literally the design of the grant to be geographic.”

That geography supported the growth of heavy industry that still dominates Richmond long after its industrial heyday and continues to take a toll on residents’ health.

Back at the contaminated marsh, Angulo recalled that she and her friends didn’t think about the long-term impacts of living in an industrial town when they were younger. As if on cue, a siren blared in the distance.

A siren goes off every Wednesday to make sure the community warning system is working in case a disaster strikes. For Angulo, it’s a constant reminder of that clear blue day in 2012 when massive clouds of black smoke blotted out the sun and stole her innocence.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,