This story by The Allegheny Front was reported in collaboration with Inside Climate News. Listen to the radio version of the piece below.

Tina and Bill Higgins have lived among forested Appalachian hills in the tiny village of Amsterdam in eastern Ohio for nearly 25 years. As they waited for their dinner at Grammy’s Kitchen, Bill said that a few years after they moved in, the Apex Sanitary Landfill was built about a mile from their house.

“There’s times you just couldn’t even go out in the summertime to enjoy a cookout or anything because the smell was bad,” he said.

They joined a class action lawsuit over the smell.

When a new company, Interstate Waste Services (IWS), bought the landfill in 2020, the Higginses said the smell improved.

But the landfill continued to get bigger. This year, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency increased the amount of waste it’s allowed to receive, to double what it was a decade ago.

What’s arriving there, along with everyday trash: oil and gas drilling waste.

Between 2014 and 2022, the Amsterdam landfill accepted over 3 million tons of solid waste from the oil and gas industry, according to state records.

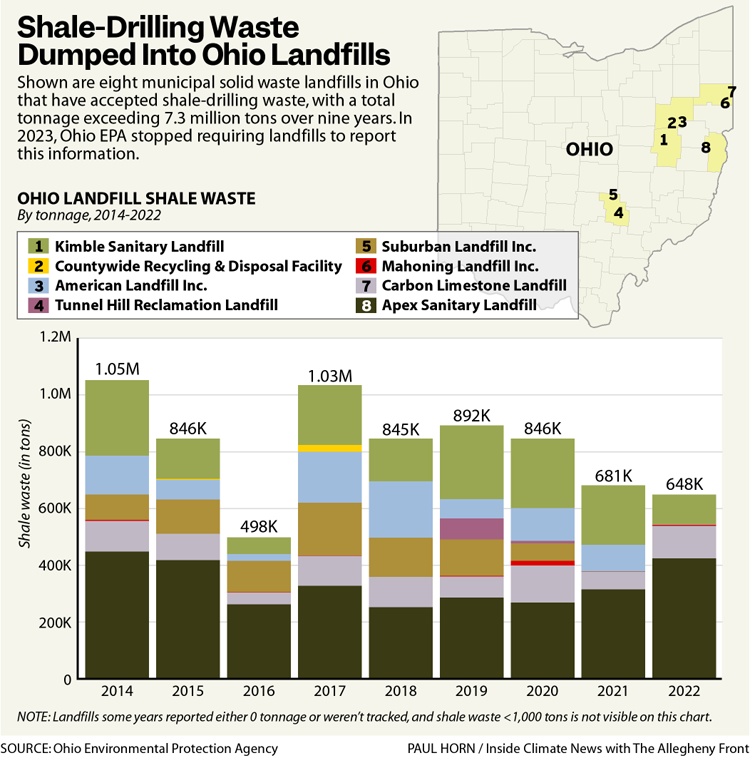

During that time, a total of more than 7.3 million tons were sent to eight landfills in Ohio. That waste can include the ground rock and soil, called drill cuttings, that come to the surface after a well is drilled deep into the ground. It could also have things like filter socks, sludges from the bottom of tanks and buildup from inside pipes.

“We don’t know …,” Tina Higgins said. “Yeah, we didn’t even know about that,” Bill Higgins finished her sentence.

(Lack of) Tracking of Solid Drilling Waste

Folks here can be forgiven for not knowing the local landfill was taking frack waste. Ohio regulators aren’t tracking it anymore, either.

“Since 2023, facilities are no longer required to report shale drilling waste separately in their annual reports,” said Ohio EPA spokesperson Max Moore in an email, though “some still opt to do so.”

Moore said this reporting requirement, which started with the shale boom, was discontinued because “the data was not consistent.”

Landfills also are not required to track the origin of shale drilling waste they receive; it could be from a well pad in Ohio, Pennsylvania or elsewhere.

“This is the perpetual problem; we don’t know,” said Melissa Troutman, who wrote an analysis of Pennsylvania’s oil and gas waste policy for the non-profit group Earthworks in 2019.

In Pennsylvania, the Department of Environmental Protection requires drillers to report where they are sending their waste.

For example, Pennsylvania drillers reported sending more than 107,000 tons of oil and gas waste to the IWS landfill in Amsterdam last year, according to an analysis of DEP records by Inside Climate News. Overall, more than 130,000 tons of Pennsylvania drilling waste went to landfills in Ohio last year.

But even in Pennsylvania, it’s hard to tell where much of it is being sent, “because regulatory agencies are not tracking shale gas waste going to landfills adequately,” Troutman said.

And that worries environmental advocates.

According to the U.S. EPA, solid waste from shale formations, like the Marcellus and Utica regions of Pennsylvania and Ohio, can contain salts, heavy metals like cadmium, volatile organic compounds such as cancer-causing benzene and radioactive materials like radium.

But the U.S. EPA doesn’t regulate it as “hazardous” waste.

As early as the 1970s, the oil and gas industry lobbied for an exemption from federal hazardous waste regulations to avoid higher disposal costs. In 1980, Congress included a temporary exemption in a federal solid waste law, and in 1988, the EPA determined that designating the waste as hazardous was not warranted, a finding it repeated in 2019.

So, there’s a patchwork of state regulations when it comes to tracking and monitoring it.

In Pennsylvania, trucks carrying waste, including from the oil and gas industry, are monitored for radioactivity before entering landfills.

In Ohio, some drilling waste, such as filter socks, sludges and scale from pipes, is required to be tested for radioactivity before it can be sent to a landfill. These are considered TENORM in Ohio – waste that is “technologically enhanced naturally occurring radioactive material.”

Tests must show radium-226 and radium-228 concentrations at less than 5 picocuries per gram above natural background levels.

But drill cuttings, which make up much of the solid waste from fracking, are not defined as TENORM in Ohio.

“Drill cuttings are considered naturally occurring radioactive material (not TENORM) and do not require radium testing for disposal in Ohio’s solid waste landfills,” said Ohio EPA spokesperson Bryant Somerville in an email.

Earthjustice attorney Megan Hunter, who has researched oil and gas waste regulations in numerous states, doesn’t think drill cuttings should be exempt from those tests, because it’s all radiation going into the landfill.

“I don’t see the distinction as particularly relevant in terms of when you’re talking about human health and risks to the environment,” she said.

How Waste Moves From the Landfills to the Waterways

One of those risks is contamination of waterways.

When it rains on a landfill, like the one in Amsterdam, water runs through all the household trash, construction debris and drilling waste.

“It’s sitting there like a tea bag, and every time it rains and things soak through, it creates this product called leachate because things are leaching,” and picking up pollutants, explained Duquesne University professor John Stolz, who has been studying the issue.

Ohio landfills collect leachate, which must be treated before being discharged into waterways.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowStolz looked over the latest leachate testing report for the Amsterdam landfill. He said if the state wants to monitor for contamination from drilling waste, landfills should measure for radium and other indicators of oil and gas waste.

“They should be measuring lithium, they should be measuring bromide and strontium,” Stolz said. If test results showed elevated levels, it would indicate that oil and gas waste was contaminating the leachate. “Why [else] would there be strontium in the leachate for a sanitary landfill? I mean, there’s not a lot of strontium in dirty diapers,” he said.

IWS said in an email that its Amsterdam landfill adheres to state regulations along with its “Waste Acceptance Plan.”

In Ohio, most leachate is sent to municipal sewage plants for treatment. IWS sends much of its leachate more than an hour’s drive north to the city of Alliance’s sewage treatment plant.

In an email, the plant operator said its biological organisms used for treatment have been consuming pollutants from Amsterdam and other landfills for decades. Last year, the sewage plant treated more than 60 million gallons of leachate from four landfills that accept oil and gas waste, according to the landfills’ annual reports.

But the sewage plant is not testing for radioactivity; it’s not required in the permit that allows it to discharge treated wastewater into a creek of the Mahoning River, a tributary of the Ohio River.

Stolz is concerned that regulators aren’t tracking or testing much of the drilling waste anywhere in the process.

“Neither the landfill or the waste treatment plant have to monitor things that we feel are important to monitor,” Stolz said. “Because they are going to be a problem downstream, literally and figuratively, over time.”

He points to one sewage plant near Pittsburgh where leachate loaded with frack waste pollutants was blamed for knocking out the treatment process. It ended up sending contaminated wastewater into the Monongahela River.

Stolz’s biggest concern is that radiation will wind up in the waterways.

A study by his team and researchers at the University of Pittsburgh backs this up. They found radioactivity in river sediments downstream of numerous sewage plants that treat leachate from landfills that accept frack waste.

“We did find a statistically significant higher amount of radioactivity downstream than upstream,” Stolz said, “and water chemistries that suggested or were indicative of discharge from oil and gas.”

A Call for Consistency in State Regulations

This kind of evidence has prompted environmental groups and radiation safety experts to call for consistent regulation of oil and gas waste.

“It varies largely from state to state,” said William Kennedy, scientific vice president with the National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. He’s written about this issue and points out one potential problem when neighboring states have differing rules, such as when Pennsylvania requires that drill cuttings be tested for radioactivity before being landfilled, while Ohio does not.

“If you had a producer … and they found a particular regulation in one state onerous or difficult to comply with, what would keep them from shipping it to another state for disposal under a different set of regulations?” he asked.

Kennedy said he and his co-authors wanted to start a dialogue among state regulators to move past the current piecemeal approach.

“So people could think through this entire problem and come up with a regulatory scheme that made sense, that would be sort of universal, that the states could adopt,” he said.

Amy Mall, who authored a report on inconsistencies in state regulations for the Natural Resources Defense Council, wants federal rules for the disposal of frack waste, such as drill cuttings, so the government can require it to be tracked and tested.

“And if they’re not regulated, they’re exempt from regulations – they’re not doing any of those things,” Mall said. “And so the public doesn’t know where this waste is going or how dangerous it is.”

A new effort in Washington seeks to change that. Congressional Democrats introduced a series of bills in the House to regulate frack waste, including one called “Closing Loopholes and Ending Arbitrary and Needless Evasion of Regulations Act of 2025.’’ It includes a long-shot bid to define the waste as hazardous. So far, only one lawmaker from Pennsylvania and one from Ohio have signed on.

Inside Climate News’ Kiley Bense and Peter Aldhous contributed to this story.

Correction: This story was updated Dec. 4, 2025, to remove a reference that Interstate Waste Services’ waste acceptance plan is issued by the regional solid waste authority.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,