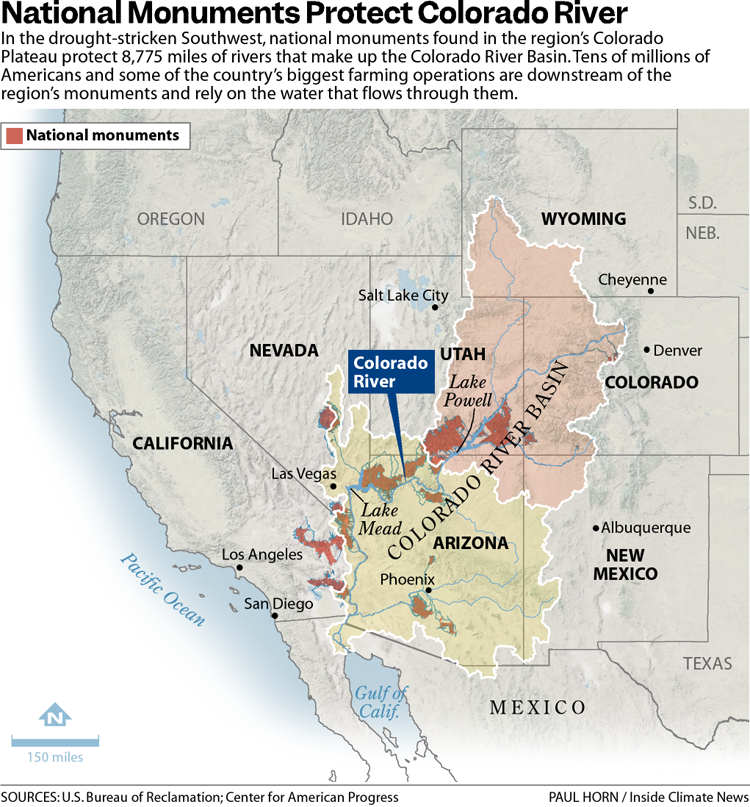

The 31 national monuments designated since the Clinton administration, which could be downsized as the Trump administration pushes to open more public lands to extractive industries, safeguard clean water for millions of Americans, according to a new analysis from the Center for American Progress.

Using geospatial data to quantify the miles of rivers and watersheds within the studied national monument boundaries, as well as the number of users who depend on that water, the report found that the water supplies for more than 13 million Americans are directly provided by watersheds within or downstream of these national monuments. About 83 percent of the water passing through these public lands has no other protection besides the monument designations, it found.

National monuments protect more than 21,000 miles of waterways across the U.S., nearly twice as much waterway mileage as the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System, the analysis also determined.

The report comes as the Trump administration weighs downsizing or revoking the designation of some national monuments.

In March, the Trump administration announced it would eliminate California’s Chuckwalla and Sáttítla Highlands national monuments before removing language from a White House fact sheet announcing that decision. The following month, The Washington Post reported that the administration was considering downsizing or eliminating six national monuments, and in June, the U.S. Department of Justice issued an opinion that the president has the power to rescind national monument designations, backtracking on a decades-old determination on the matter.

During Trump’s last term, Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante national monuments, established by the Obama and Clinton administrations, respectively, were shrunk to fractions of their original sizes, but they were restored by President Joe Biden after he took office.

If national monuments are downsized or eliminated, the areas surrounding a waterway will lose protections from extractive industries, including oil and gas drilling, mining and grazing. Contamination from those industries could seep into streams and, in turn, rivers. Those industries also use water, sometimes vast amounts in arid regions, further reducing the supply that flows to nearby communities. (In certain cases, some mining and grazing are already permitted on national monument lands, but the activities are limited in scale and more regulated than they are outside the monuments.)

“Landscapes and waterways go hand in hand,” said Drew McConville, a senior fellow for conservation policy at the Center for American Progress and a co-author of the report. “The clean water depends on what comes into them from natural lands … Just protecting the wet stuff itself doesn’t guarantee that you’re keeping [water] clean and durable.”

The portion of historically marginalized communities living within the watersheds of the national monuments is greater than the average for watersheds nationally, it found. Twenty-three of the monuments studied are also found in regions expected to face water shortages due to climate change in the coming decades, making the arid regions downstream even drier.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, for example, protects 2,517 miles of waterways, according to the analysis, and nearly 90 percent of the watersheds within the monument are expected to see declines in their water levels. The monument straddles the Upper and Lower Colorado River Basins, with the Paria and Escalante rivers flowing within its boundaries and Lake Powell, the nation’s second-largest reservoir, just to its south.

The monument is often thought of as a sparse, arid region, which it is, said Jackie Grant, the executive director of Grand Staircase Escalante Partners, a nonprofit focused on protecting the monument that has spent $11 million to protect the Escalante River watershed and all its tributaries. It remains vital to the Colorado River System, which millions of people in the Southwest rely on. Grand Staircase-Escalante helps slow water from the Paunsaugunt Plateau in Bryce Canyon National Park, much of which starts as snowpack in the park before melting and flowing downstream.

“People don’t think of water when they think of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument,” Grant said. “So when we can bring this view of water and how important it is to the protection of the monument, it helps us put another building block in our case for supporting the monument, because not only is it important for the animals, the native plants, the geology and the paleontology, water plays a huge role in the monument, and the monument protects the water itself.”

Stretching across 1.87 million acres of public land, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is one of the country’s most expansive national monuments, protecting scores of wildlife as well as archeological resources in southern Utah. But a nine-billion-ton coal deposit is buried in the center of the monument along with deposits of minerals, including uranium and nickel. The Trump administration has long touted boosting the country’s coal production, and has established a pro-mining agenda this year.

“It’d be very easy to contaminate either one of those rivers if mining were to take place in the center section of the monument,” Grant said.

Margaret Walls, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future who has studied national monuments but was not part of this study, said national monuments are designated to protect cultural or historical landmarks, and it can be forgotten that they can also serve purposes like safeguarding water. Though she noted that even if monument protections are loosened, the areas remain federal lands, and their changes in status do not guarantee they will be developed.

“We don’t protect waterways the way we do land,” Walls said, “we’re going to get those water benefits by protecting the land.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,