This fall, when the World Meteorological Organization confirmed the grim news—a record 3.5 parts per million annual increase in the global concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere—there was a somber, unspoken backstory.

As the WMO compiled the numbers, it was preparing for the possibility that the central player in that monitoring effort—the United States—could withdraw at any time.

Just weeks after President Donald Trump returned to office in January, the White House budget office circulated a memo outlining its plan for an unprecedented cut to funding for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with climate research taking one of the biggest hits. The president’s budget proposal, released in May, gave details: a 30 percent slash in agency funding, including the elimination of its research office and Global Monitoring Laboratory. Under that plan, the historic observatory on Mauna Loa Volcano in Hawaii, which in 1958 launched the measurements that charted the definitive record of the Earth’s build-up of carbon dioxide, would be gone.

“That was a shock for us,” said Oksana Tarasova, senior scientific officer for the WMO in Geneva. “Given the leading role of NOAA and given that they are the backbone of what we [have been doing], nobody can imagine that this may happen.”

The funding deal Congress passed and the president signed in November to end the nation’s longest government shutdown gave NOAA’s climate program at least a temporary reprieve. NOAA’s funding, like that of the majority of federal agencies, is supposed to continue for the time being at the level Congress approved for the prior fiscal year. But a cloud of uncertainty hangs over the program, both because of questions over how the Trump administration intends to carry out that directive and over what will happen in future budgets.

That puts the global scientific community in a difficult position. Although observations from 179 stations go into calculating the global average CO2 concentration, NOAA provides 40 percent of the observations—not just from Mauna Loa, but from stations across the continental United States, as far north as Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska, and at the U.S. observatory at the South Pole in Antarctica. NOAA also has been in charge of quality control, running calibration tests at its Global Monitoring Laboratory in Boulder, Colorado, to ensure that equipment used around the world provides measurements that are accurate, comparable and repeatable.

It is largely thanks to NOAA’s scientific work that the WMO was able to say with confidence that the atmosphere’s global average CO2 concentration in 2024—423.9 parts per million (ppm)—was 3.5 ppm higher than in 2023, the largest annual increase since modern measurements started in 1958. (NOAA’s own results showing the same trend, which came out in April, were included in the WMO average announced Oct. 15.) The readings pointed to the likely reason for the jump—the world’s forests had lost some capability to sponge up CO2 from the atmosphere, due to severe drought and fires in the Amazon and southern Africa in 2024, the WMO said in its report.

Only future measurements will tell whether that loss was a blip or a shift into a new trajectory. But to ensure those measurements will be recorded, the global scientific community is planning for a future of long-term carbon measurement with less reliance on NOAA. That means a reduced role for the United States in the science that it pioneered.

“The Young Man With the Machine”

The Mauna Loa Observatory was established in the 1950s by two U.S. giants in meteorology. Robert Simpson, the first director of what was then called the National Hurricane Research Project, saw the remote location two miles above the Pacific Ocean as “an ideal natural laboratory for geophysical and atmospheric research,” he would later write. Simpson, who went on to co-develop the well-known 1-to-5 Saffir-Simpson scale of hurricane intensity, teamed up on the Mauna Loa idea with Harry Wexler, then chief researcher for the U.S. Weather Bureau, the predecessor to NOAA’s National Weather Service. Wexler, the first scientist to deliberately fly into a hurricane to study it in 1944, is remembered for his later pioneering work on weather satellites.

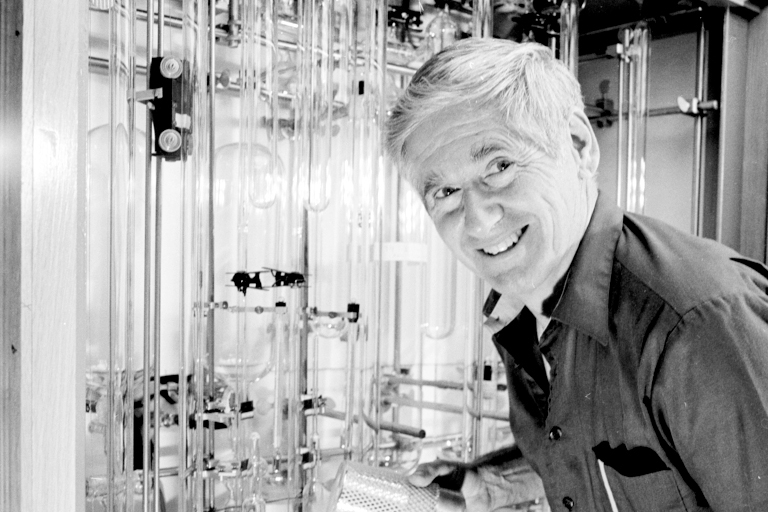

Early research at Mauna Loa included studies of atmospheric ozone and solar radiation, aided by the high elevation and Hawaii’s clear skies. But a young scientist, Charles David Keeling, brought Wexler the idea that would seal Mauna Loa’s place in scientific history. As a postdoctoral fellow in geochemistry at the California Institute of Technology, Keeling had developed a system for measuring the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere with precision. And Keeling’s work indicated—contrary to most scientific thinking at the time—that continuous monitoring of the atmosphere with the right instruments and at the right location would yield crucial data needed to test the then-nascent science of climate change.

Wexler saw it as an ideal contribution to an international scientific event that the United States was spearheading—the International Geophysical Year. In 1957 and 1958, timed to coincide with the projected peak of the regular cycle of solar flares and sunspots, scientists from 67 nations planned to conduct investigations into an array of Earth and atmospheric phenomena, from glaciers to cosmic rays, from plate tectonics to solar activity. (The event is perhaps best remembered for the launch of the first manmade satellites, with the Soviet Union’s Sputnik beating the United States’ Explorer 1 by four months.) As part of the International Geophysical Year, scientists hoped to measure atmospheric carbon dioxide.

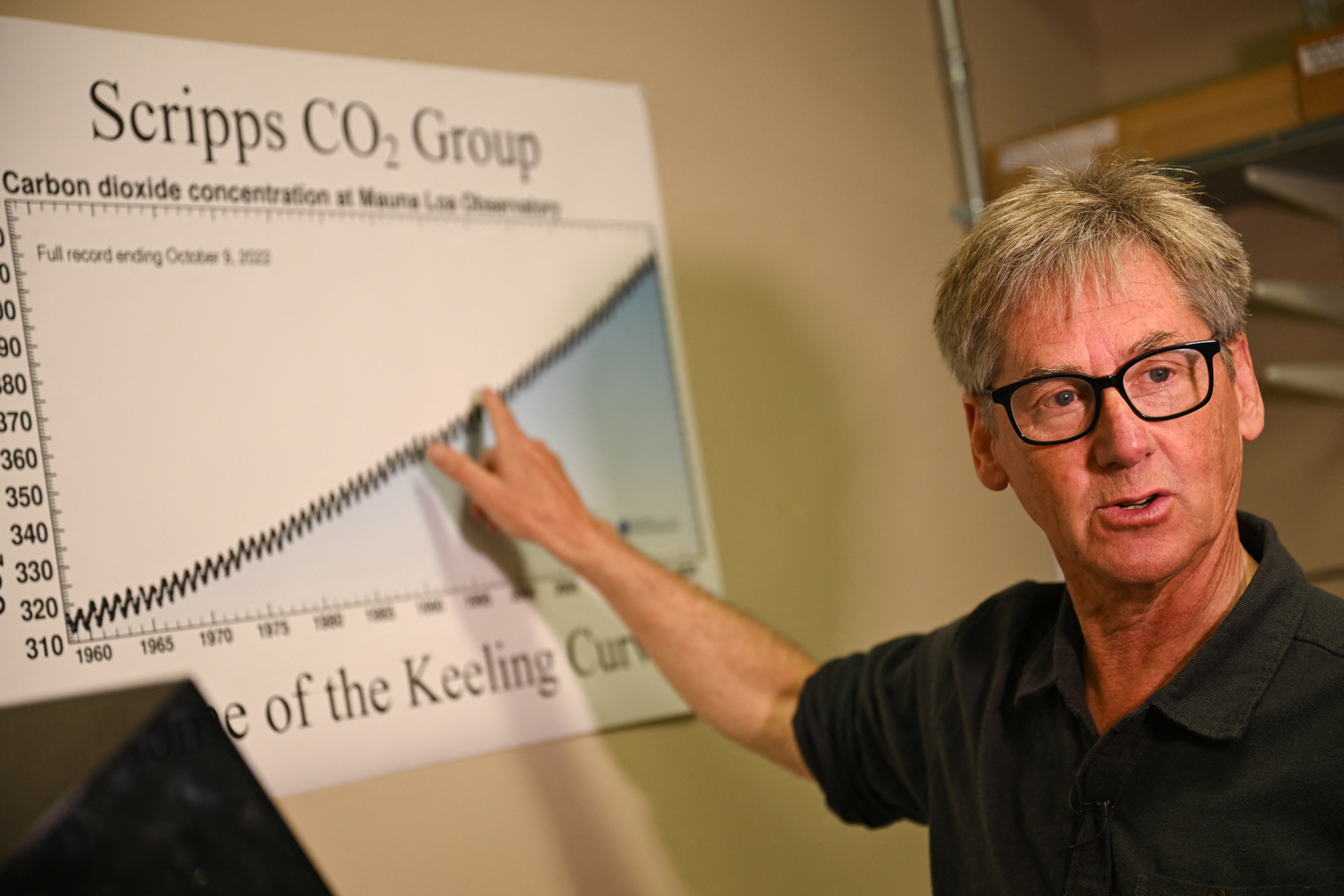

“There was a recognition that the atmosphere had more than just winds and temperatures and humidity, it also had chemistry,” said Ralph Keeling, son of Charles, who followed his father’s footsteps into science and a professorship at a NOAA partner organization, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

Before Charles Keeling, no one had ever proposed long-term, continuous monitoring of CO2. Scientists believed the concentration would vary greatly depending on location, with no clear time trend. And a significant equipment upgrade would be needed, an infrared spectrometer, to streamline the laborious process Keeling had been using. Keeling recalled the dubious reaction to his idea from Carl-Gustaf Rossby, then director of the International Meteorological Institute in Stockholm, at an International Geophysical Year planning meeting. “Ah, the young man with the machine,” said Rossby, renowned for his discovery of the planetary waves in the atmosphere now known as Rossby waves.

“He seemed upset at this abrupt new American plan to buy expensive gadgetry to measure CO2,” Keeling wrote in NOAA’s 20th anniversary remembrance of Mauna Loa in 1978.

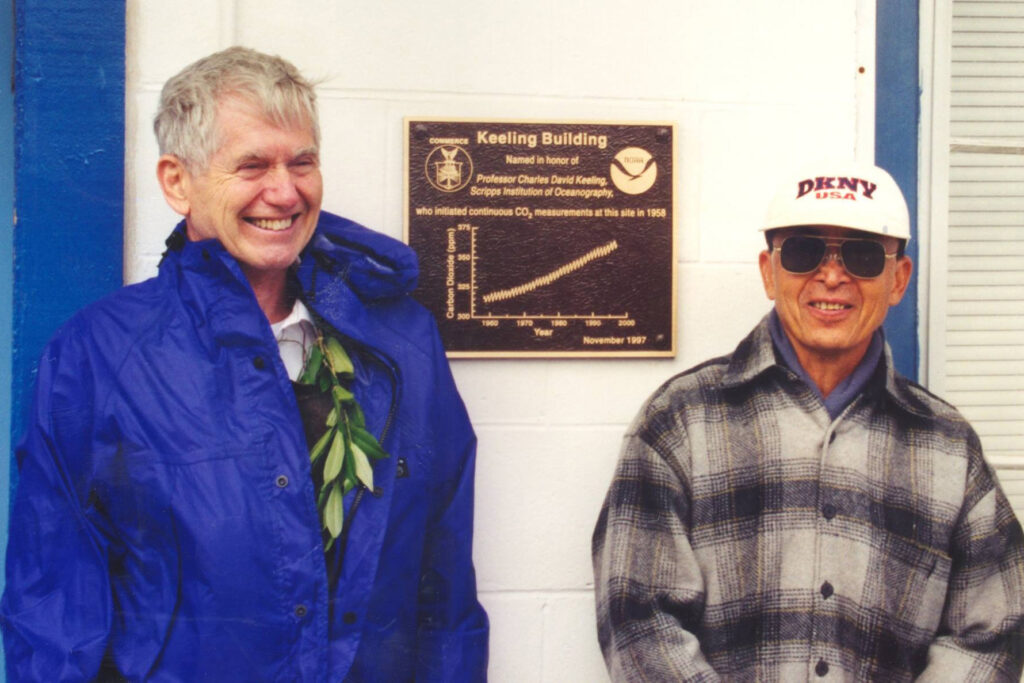

The first month of CO2 readings at Mauna Loa, in March 1958, showed an average atmospheric CO2 concentration of 315.71 ppm. A little over a decade later, at a symposium on the long-term implications of atmospheric pollution, Keeling was able to show the steady transformation in Earth’s atmosphere. The monthly mean CO2 at Mauna Loa in March 1969 was 325.63 ppm, more than 3 percent above the first reading, with a steady up and down wave pattern each year—“a remarkably regular annual pulse,” Keeling wrote—due to plant life in the Northern Hemisphere absorbing CO2 as it greened in spring and summer, then releasing it in fall and winter.

Ralph Keeling, who has called his father’s Keeling Curve “an icon of the human imprint on the planet,” said that the senior Keeling bucked the expectations of his colleagues by continuing to work on monitoring CO2 even after the pattern of increasing concentration was clear. “After several funding cycles, his peers would say, ‘Hey, look, you’ve already shown the CO2 going up,’” Ralph Keeling recalled. “‘You’ve checked that box. Time to move on, right?’”

But Charles Keeling rebuffed that idea, and instead sought to show the value of sustained monitoring. “His work was a role model for the importance of long-term observations: how important they are, and how hard they are to keep going,” Ralph Keeling said. “Now we find ourselves in the midst of this crisis where long-term observations, among other things, are on the chopping block. But their loss is especially damaging because their value derives from their continuity and their brilliant ability to track how things are changing over time.

“If there’s an interruption, you can’t just get back to where you were, you’ve lost it forever,” Ralph Keeling said. “A measurement not made is a measurement never made.”

Charles Keeling fought to keep Mauna Loa’s measurements alive through federal budget cuts in the 1960s, and over the years, the work would receive bipartisan support and international acclaim. The project was adopted by NOAA when President Richard Nixon established the agency in 1970. Mauna Loa contributed the longest available record to the worldwide network of CO2 monitoring, established by the WMO in 1989. Keeling would receive the nation’s highest scientific honor, the National Medal of Science, from President George W. Bush in 2002, three years before his death at age 77.

Mauna Loa measurements did experience a brief pause in 2022, when lava flows buried one mile of the access road and cut electricity to the station. (Mauna Loa happens to be the world’s largest active volcano.) But a far greater upheaval came at the start of Trump’s second term in office.

“38 Mauna Loas in Europe”

Trump’s budget director, Russell Vought, revealed the plan to eliminate NOAA’s Oceanic and Atmospheric Research (OAR) and all climate laboratories in a budget preview circulated on Capitol Hill in the spring. He outlined ideas for “a leaner NOAA that focuses on core operational needs, eliminates unnecessary layers of bureaucracy, terminates nonessential grant programs, and ends activities that do not warrant a Federal role.” The memo envisioned a NOAA focused on weather data without collecting climate data. Vought had been an architect of the conservative policy plan Project 2025, and the NOAA proposal echoed it.

“OAR is … the source of much of NOAA’s climate alarmism,” Project 2025 said. “The preponderance of its climate-change research should be disbanded.”

The wide array of businesses, states and academic institutions that have been lobbying to maintain NOAA funding reject Project 2025’s characterization of the agency’s climate work. “It’s factual information, based on observing systems and consistent over time, so trends become obvious,” said Franklin Nutter, who served as president of the Reinsurance Association of America for 34 years before his retirement in November. “The insurance sector views the data and the research related to the data not as alarmist, but as important for our industry as companies look at pricing models, risk assessment models and where they’re writing coverage,” Nutter said in an interview earlier this year.

Nevertheless, Trump’s formal budget proposal, unveiled in May, said that $102.3 million could be saved and 216 positions eliminated by terminating NOAA’s climate laboratories and cooperative institutes, including the Global Monitoring Laboratory, based in Boulder, Colorado, and its observatories at Mauna Loa and two other sites in Hawaii; in Utqiaġvik, Alaska; on American Samoa; and at the South Pole in Antarctica.

The cuts would shave a small fraction of 1 percent from the federal government’s $1.7 trillion discretionary budget. But they would have huge implications for global climate science.

“There are some people who think if we switch off the observations, the problem is gone,” said Werner Kutsch, director general of the Integrated Carbon Observation System (ICOS), an intergovernmental organization supported by 16 European states. “This is, of course, complete rubbish.

“You can switch off the observations in the U.S., but there’s still, I sometimes say, 38 Mauna Loas in Europe,” Kutsch said, referring to the monitoring stations across the continent. “We will continue this record. And we will continue to show that the CO2 increase in the atmosphere is even accelerating. That’s the problem that we see at the moment.”

Now, as Keeling predicted they would, scientists are looking at the long-term CO2 trend to understand what the record increase in 2024 says about where the planet is heading. One reason for the bump was clearly a strong El Niño year—the warm phase of a tropical Pacific Ocean cycle marked by drier vegetation and forest fires. Still, last year’s increase in atmospheric carbon concentration was greater than that in previous El Niño years. Could we be seeing signs of a negative feedback loop in which climate change will be more difficult to manage because of the changes that have already happened?

“That might be the big unknown for the future,” Kutsch said. “Even if we might be able to reduce emissions, we might have already caused so much damage to the natural ecosystems that they are not able to take up as much from the atmosphere as they did in the past.”

In the WMO press release on the data, Tarasova made a plea that was an unmistakable reference to the situation in the United States, by then in the midst of a government shutdown. “Sustained and strengthened greenhouse gas monitoring is critical to understanding these loops,” she said.

Status Quo: Uncertainty

Bipartisan opposition has emerged in Congress to the Trump plan to slash NOAA. Lawmakers balked at the potential economic hits to agency partners, including in Republican strongholds like Oklahoma, Alabama and Florida, from the deep proposed research cuts. The Senate Appropriations Committee voted to maintain NOAA funding, and while the House Appropriations Committee approved a small cut to the agency budget, it included a provision directing NOAA to keep its laboratories and cooperative institutes open, “given their essential role in advancing weather forecasting, climate science, and oceanographic research.”

But Congress never approved those fiscal year 2026 bills. The White House pushed instead for a continuing resolution that would maintain the status quo—fiscal year 2025 funding levels—through fiscal year 2026. After a record 43-day shutdown due to a partisan rift over expiring health care insurance subsidies, Congress agreed to fund much of the government, including most science agencies, on a continuing resolution through Jan. 30, while negotiations on fiscal year 2026 budget bills continue.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowHowever, the status quo means uncertainty for NOAA, especially for climate research. In August, the Office of Management and Budget released a spending plan for NOAA showing that the Trump administration was spending 25 percent less than Congress had appropriated in the fiscal year 2025 budget for climate research. Vought has long sought to challenge the law limiting the president from cancelling, or impounding, funds appropriated by Congress. And advocates for outside groups that rely on NOAA funding say the Trump administration’s view is that a continuing resolution gives it greater leeway on spending.

“I’ve heard this with my own ears from administration folks, I’ve seen it in reporting and I’ve heard it from the Hill,” said Emily Patrolia, founder and chief executive of ESP Advisors, which represents ocean and coastal organizations engaging with the federal government. “The way the administration is interpreting a continuing resolution is that they pretty much have the authority to spend the way they want. And in the absence of Congress passing [fiscal year 2026] regular order appropriations bills, they are going to spend assuming the [fiscal year 2026] president’s budget request is the way they should be spending their money.”

For now, Mauna Loa is operating on a limited basis, as it has been since the 2022 volcanic eruption reduced access, a NOAA spokesman said in an email. Sources familiar with its operations say the station has electricity thanks to solar panels, and NOAA began posting its monthly average Mauna Loa CO2 readings on its website again, after a hiatus during the government shutdown. The NOAA spokesman said all of the other Global Monitoring Laboratory facilities are currently operational. He declined to comment on whether there may be cuts while the continuing resolution is in place.

“It’s NOAA’s longstanding practice not to discuss personnel or internal management matters,” he wrote.

Patrolia said there continues to be “a black hole of information” around the impact of budget-tightening on NOAA, with federal employees unable to talk, Congress lacking information from the executive branch and outside entities, like the institutions that rely on NOAA research grants, being careful not to make waves. “They’re aware of the political environment,” she said. “They’re more likely to get their grants unstuck if they go through an informal, quiet advocacy route.”

In the meantime, there’s no question that NOAA has been diminished. Members of Congress estimate that the agency has lost 2,200 personnel since the start of the year through buyouts, resignations and the elimination of provisional employees.

“You Cannot Buy Experience”

For the international climate science community, the uncertainty around NOAA’s future is deeply jarring. Mauna Loa may be the most recognizable symbol of the United States’ leading role in CO2 monitoring, but even more vital to the effort is the less visible work that NOAA does to ensure that all labs worldwide that monitor CO2 use calibrated instruments and produce reliable results.

“NOAA produces the reference standard,” Tarasova said. “If they stop doing that, we don’t have an anchor.”

In addition to high-quality instruments and a well-equipped lab, experienced personnel are needed, with training to ensure continuity, and a continuous effort to improve processes, she said.

“You can’t organize it overnight,” Tarasova said. “You may have some billionaire who wanted to donate this stuff, and then you could build the lab, but you cannot build a lab with 30 years of experience in keeping the standard. You cannot buy experience.”

Tarasova is hopeful that NOAA climate research will continue, to enable the international carbon monitoring program to make a more orderly transition to a future less reliant on NOAA. Discussions with scientists in other countries, including in China, Australia, New Zealand and throughout the European Union, are underway, she said.

“It is really very sad that we come to this through such a frightening experience, when the community is really threatened by losing the value of what has been supported by NOAA,” Tarasova said. “We should have built this redundancy much earlier, just to make sure that the global system does not rely on just one country.”

Some involved in the rethinking of global CO2 monitoring find it unfathomable that the United States would voluntarily step back from its historic role. “If a country is leading scientifically in a specific area, and then you cut the budget out of it, you’re not making America great again. You’re making America weak again,” said Kutsch, of the Integrated Carbon Observation System. “You may like science or not, but of course, there’s a kind of competition in science … And when America drops from the first place to whatever, fifth place? … For me, logically, this is completely not understandable. Why would you give up a leading position?”

Bob Berwyn contributed to this report.

Editors’ Note: The story was corrected to note that the Integrated Carbon Observing System is an intergovernmental initiative of 16 European states, not part of the WMO.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,