The last 10 global climate summits have played out on vastly different stages: from the hopeful consensus of the Paris Agreement through a subsequent pandemic shock, petrostate spectacles and a hoped-for reckoning with environmental justice in the Amazon. But the new scripts often seem like reruns, with minor plot twists; a new villain, a new planet-saving technology or a new text that raises more questions than it answers. The struggle remains unresolved. A close look at the settings and the actors shows a process paralyzed between performative self-awareness and transformative, meaningful action.

2015 – Paris, COP21

COP21 in Paris marked a pivotal moment when science, power, vulnerability, and ambition aligned, and politicians found the will to face the global warming threat head-on with a pact that would finally identify and challenge the fossil fuel industry.

After years of climate bickering, the Paris talks unfolded in a setting designed for consensus. The world watched closely as leaders spoke about unity and resolve, while diplomats worked in the back rooms to keep everyone on script. The result was an agreement that convincingly signaled a change in direction and translated science into the language of political commitments.

There was global praise for the convincing performance because the actors remained in character, discussing limits, responsibility and shared risks. The machinery of global governance appeared to give those words some binding weight. But the agreement’s lasting impact would hinge on what happened in the subsequent acts.

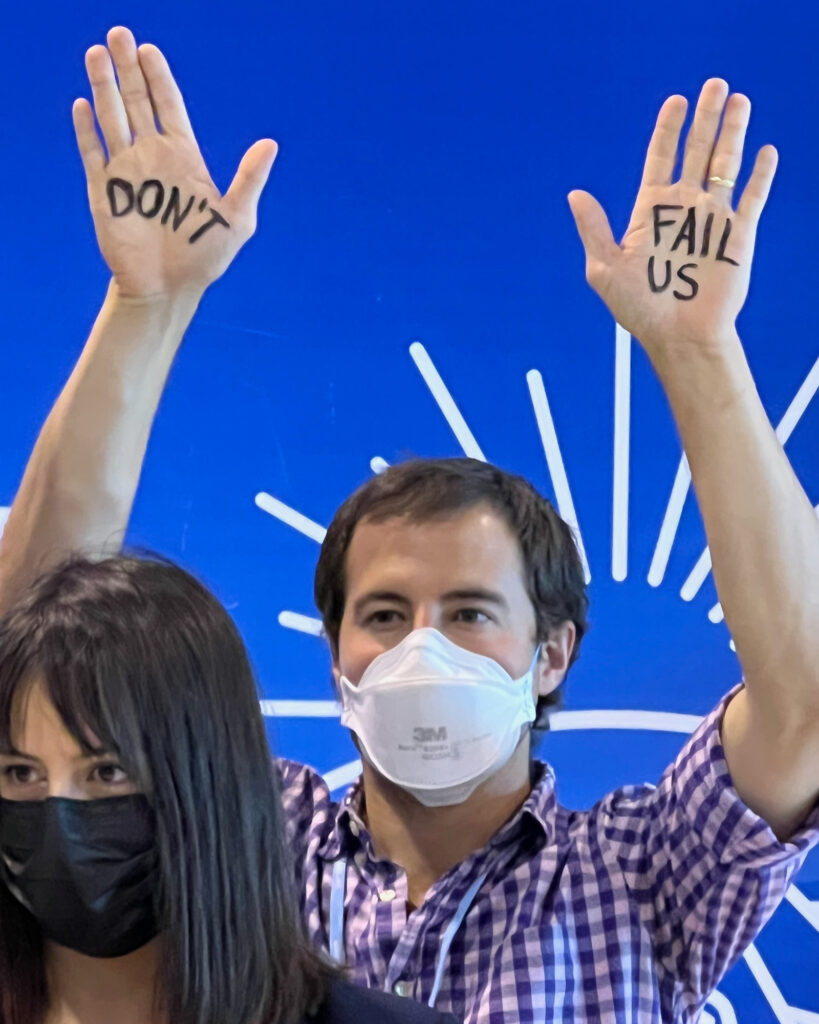

2021 – Glasgow, Scotland, COP26

If Paris glimmered with light and hope, COP26 in Glasgow felt Gothic. Cold rain splashed the stone of the city’s abandoned industrial buildings, relics of the extractive economy that caused the climate crisis. Still, it couldn’t wash away the trauma of about 15 million pandemic-related deaths and the economic shocks and political fragmentation that had already started reshaping the world’s climate commitments.

During negotiations, the science left no room for interpretation. The 2018 1.5C global warming report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change demonstrated the consequences of further delay for ecosystems, economies and human lives. But political systems struggled under the strain of the pandemic. The script was sharpened with new language and commitments, but the Paris Agreement was softened in practice, as governments weighed climate action against economic recovery and other domestic pressures.

Pandemic restrictions also reshaped public participation. Host country organizers started treating civil dissent as a risk to be mitigated rather than as voices to be heard. The protests that had long been a defining emotional counterpoint to the technocratic hum of the talks were often limited to chilly, rain-lashed outdoor zones, penned in by tall metal fencing, visible but constrained. The measures were presented as temporary and necessary, but cast flickering shadows over the climate talks.

2022 – Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt COP27

The shadows of rising authoritarianism deepened a year later. COP27 was held in a military-ruled country that’s heavily dependent on fossil fuels, on a stage shaped by centralized power and control. The conference center was surrounded by tanks, troop carriers and security agents with radios wearing dark suits and even darker sunglasses, trying to blend into the shadows of cell phone towers disguised as palm trees.

Moral urgency and scientific warning converged at COP27 in Sharm el-Sheikh, where Indigenous activists protested climate injustice as researchers presented evidence showing how global warming threatens regions such as Egypt’s Nile Delta.

Despite the carefully controlled setting, global climate justice advocates were able to put the irreversible impacts and costs of global warming into the heart of the COP narrative with a loss and damage agreement making it harder for high-emissions countries to further delay taking some responsibility. For delegates from Global South countries, lived experience was now center stage, with the script calling for accountability, solidarity and repair.

But the breakthrough on loss and damage did not reset the pace of the talks, which carried on with the rituals of global climate diplomacy; new texts and ceremonies, but little recognition of urgency after a year marked by cascading disasters, including floods in Pakistan that left more than 2 million people homeless.

Climate extremes overlapped and compounded, pushing humanitarian relief systems beyond their limits. Scientific projections about the impacts of global warming turned into daily headlines. Inside the venue, the disconnect was apparent: delegates sipped lattes in busy coffee shops while just across the aisle, scientists spoke to rows of empty seats—ignored like Cassandra—graphically showing how much of the Nile Delta could vanish by 2100.

2023 – Dubai COP28

In 2023, the largest COP ever convened drew about 80,000 participants. To many climate activists, muzzled from the start of the talks, it felt like the fossil industry was rewriting the script, with its chosen actors dominating the climate stage.

Fossil fuel royalty presided, with Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, the chief executive of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company, one of the world’s largest oil producers, at the helm of the global climate talks. And with thousands of lobbyists from fossil-dependent industries present, it felt more like an occupation than a negotiation.

At COP28 in Dubai in 2023, scenes of grief and solidarity among climate activists unfolded alongside the summit’s futuristic architecture and displays of energy abundance, underscoring the widening gap between lived climate impacts and the tone of the world’s largest climate talks.

Fossil fuel power, which had previously orbited the conferences, was now the center of gravity, trying to convince the world that global warming could be addressed through fossil-fueled excess, centralized authority and technological control: the very forces that caused the climate crisis. In Dubai, that worldview was on display in glittering glass and steel towers, and in the horsepower of rows of the latest muscle cars available to rent by the hour along the city’s beachfront commercial strip. Advocates for restraint, redistribution and planetary limits were relegated to the role of offstage extras, issuing muffled shouts through the curtain.

The streets around COP28 in Dubai showcased conspicuous wealth and energy excess, with luxury cars and illuminated shopping districts framing the world’s largest climate summit.

As the curtain fell on COP28, the future of global efforts to avert climate collapse seemed more in jeopardy than ever. Even the process of selecting the next host country, often routine, became contentious. Russia, under economic sanctions after it invaded Ukraine, threatened to use its veto power in the U.N. climate process to delay the selection and steer the choice toward a nominal ally to avoid more diplomatic isolation.

2024 – Baku COP29

Baku, one of the birthplaces of industrial oil and gas production and its associated climate pollution, seemed an apt choice for COP29, which signaled the persistence of fossil fuels, and the stage was already set. The talks were in the hands of Mukhtar Babayev, a former high-level oil and gas industry executive, who was immediately cast as the potential new villain in the latest installment of the annual climate drama, leading some to ask who is writing the scripts.

At COP29 in Baku, civic climate action unfolded in carefully staged settings. A packed People’s Plenary amplified civil society voices, activists staged symbolic protests, and Indigenous leaders opened sessions with ceremony and lived experience. The scenes captured a defining COP tension: visible moral urgency confined to parallel spaces outside the core negotiations.

There were no big expectations for the summit, which also raised questions about whether it’s worth holding the talks each year when they start to look like reruns, except maybe with different sets. After Dubai’s spectacle, Baku’s COP was in the town’s soccer stadium, just a stone’s throw from the last stop on the main subway line, where men played dominoes in the park and commuters mingled with COP participants in the line to buy Kebabs and falafel. Most people on the street didn’t know why the stadium was lit up at night in neon hues for several weeks, and that thousands of people inside were discussing the fate of the planet’s climate.

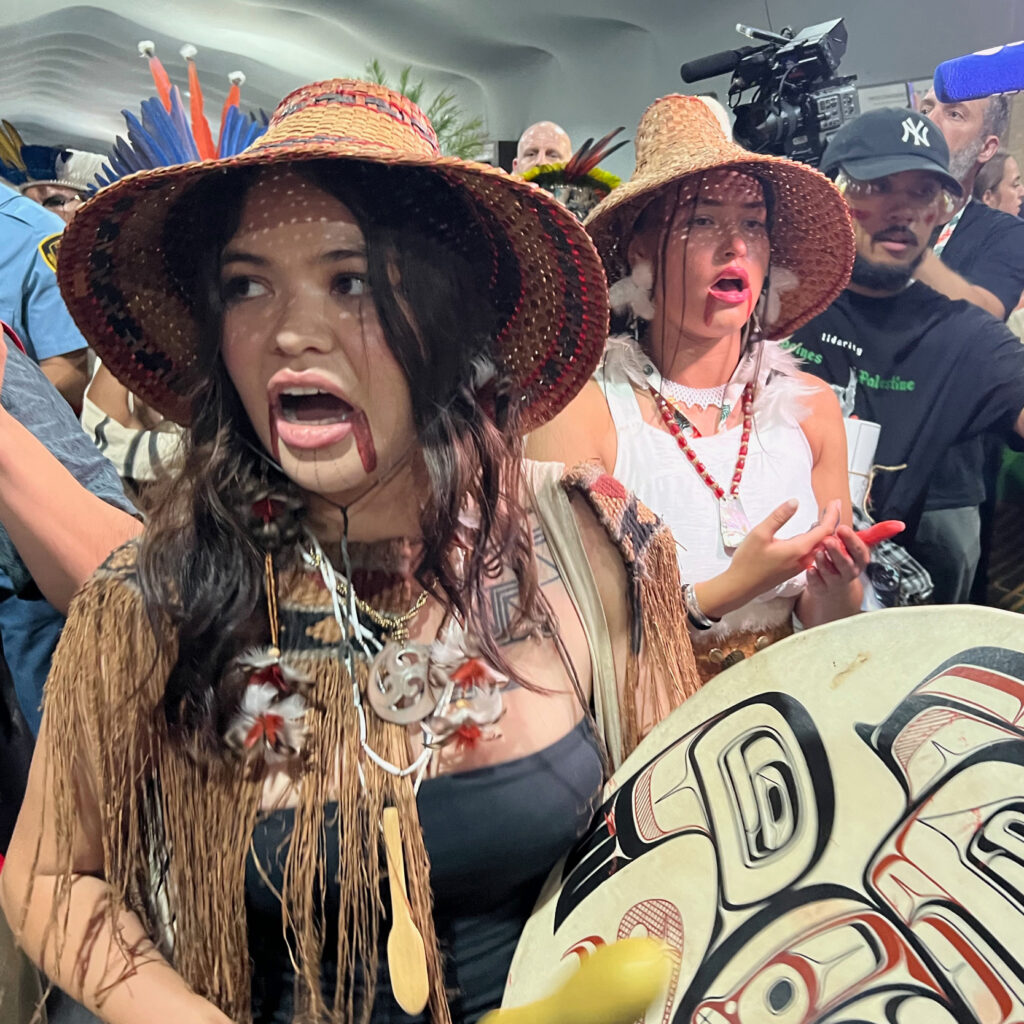

2025 – Belém COP30

If the past few climate summits were held on fossil fuel industry turf, COP30 in Belém was billed as a reset. Nature got a leading role. Proximity to the vast, living Amazon system, which helps shape global climate patterns, could restore some life to the sterile proceedings, reminding negotiators that planetary physics, not political theater, ultimately sets the limits.

But Belém is not a pristine rainforest sanctuary. It’s a large industrial harbor town shaped by centuries of colonial extraction and uneven development, and the conference itself was held inside temporary inflatable structures spanning the length of an old airport runway and lined with hundreds of diesel-powered generators to fuel massive arrays of air conditioners.

Still, Indigenous representation helped give the climate conference a stronger moral center than the preceding talks. Leaders and activists from the Amazon and other regions spoke with authority about land, memory and survival, to some degree revitalizing the legitimacy of the entire process. But some Indigenous participants warned that visibility was not the same as agency. As one Gwich’in protester put it, the summit also used Indigenous people by inviting them to embody values and urgency, but rarely empowering them to shape outcomes once the cameras moved on.

Indigenous activists advocating for their communities and ecosystems were visible and vocal at COP30, but they still don’t have formal representation in the rooms where climate policy decisions are made.

Whether Belém marked a real inflection point or another carefully crafted script update won’t be clear until more chapters in Earth’s climate story are written. Forests, rivers and oceans, and their long-term defenders were more central to the story than before, but the institutions of global climate policy, with their timelines and hierarchies, seem remarkably resistant to fundamentally changing course. COP30 suggested possibilities and constraints. The stage can be redesigned and the cast and symbols can change, but the plot won’t until there is a power shift.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,