There is a place in the world, one that is among the most vulnerable as the global climate warms, where an extraordinary gesture of hope has endured for a quarter century.

The scope of the effort is almost incomprehensible, both for its sheer size and persistence on a low-lying peninsula, where the delineation between land and sea has always been somewhat unclear and is becoming less so. Here, sea level rise is accelerating at some of the most extreme rates on Earth, while hurricanes increasingly are swirling ashore with an unprecedented ferociousness.

The focal point for all this hope—and work—is the Florida Everglades, where a $27 billion restoration effort is among the most ambitious of its kind in human history. More is at stake than preserving the singular beauty of the sawgrass prairies of Everglades National Park or cypress swamps of the Big Cypress National Preserve. Or the many other protected lands here, including the Everglades Headwaters National Wildlife Refuge, Arthur R. Marshall Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge or Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park. Or the more than 70 endangered and threatened species that reside within the watershed.

At the heart of the vast effort is the Everglades’ lifeblood water. In a state bounded on three sides by seawater, where water courses through underground aquifers and some 50 inches of rain falls annually, a series of historic efforts to drain the Everglades have made modern Florida possible. They have also pushed the state’s most important freshwater resource to the brink.

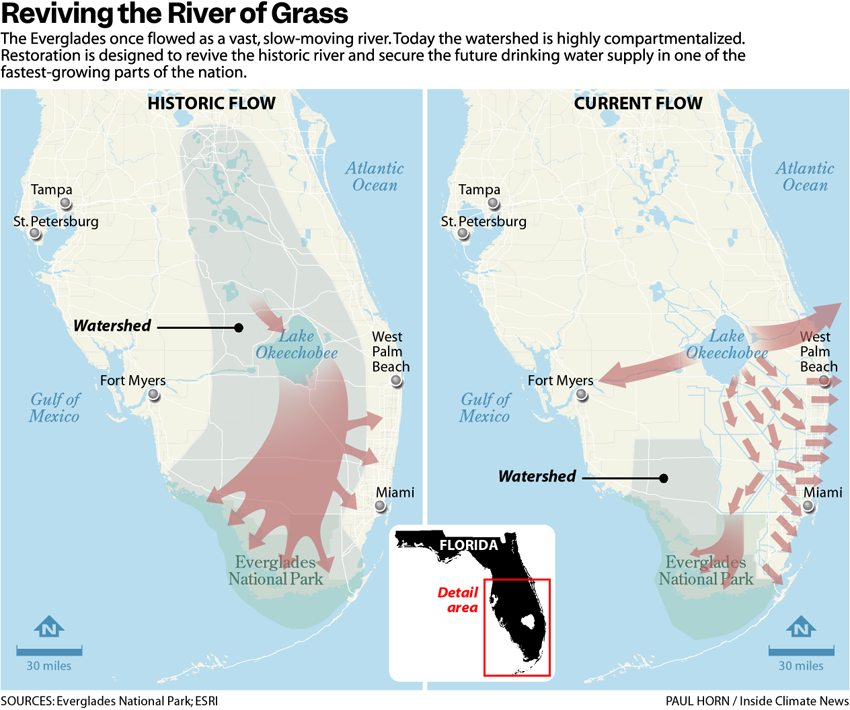

Every day, some 1.7 billion gallons of freshwater that once spilled over the southern shore of Lake Okeechobee and eventually flowed into the sawgrass marshes of the river of grass instead are carried through a series of canals and out to sea. That amount exceeds what is consumed in South Florida daily, and during times of high water the state’s flood control procedures require that even more freshwater be discharged to the coasts. The waste of so much freshwater would be problem enough. But the discharges also can overwhelm the delicate estuaries east and west of the state’s largest lake and, during the warm summer months, spread blooms of toxic algae, an issue that has become more persistent in recent years.

Everglades restoration is designed to recapture this freshwater and revive the watershed where it once flowed, with the overarching goal of securing the future drinking water supply in one of the fastest-growing parts of the nation. In this sense, the effort represents a remarkable investment in the future in a place where the future can feel less certain because of climate change.

“You can’t have a failure of imagination when you’re trying to address these issues. You’ve got to be operating at an appropriate scale,” said Shannon Estenoz, chief policy officer at the Everglades Foundation, an advocacy group.

“Don’t look at infrastructure as permanent,” she said. “The worst failure is you can’t imagine a landscape re-engineered. Or you can’t imagine an engineered landscape re-engineered.”

When former President Bill Clinton signed the Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP) into law in December 2000, the culmination of many years of scientific study and at times acrimonious political advocacy, nothing like it had ever been attempted anywhere.

Over the intervening 25 years, the landscape across an 18,000-square-mile expanse, larger than the state of Maryland, has undergone an extensive reshaping. Hundreds of miles of canals have been backfilled, enormous new reservoirs excavated and water control structures blown up, all to restore a more natural flow of water where for more than a half century some of the most complex water management infrastructure in the world has allowed for the urban jungles of South Florida to flourish alongside the wild Everglades.

The effort consists of dozens of massive infrastructure projects. The largest and most expensive is a $3.5 billion reservoir to be situated among sprawling sugarcane fields south of Lake Okeechobee, in a 1,100-square-mile region called the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA). Once complete, the reservoir, designed to help reconnect the lake with the sawgrass marshes to its south, will be the largest of its kind that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has constructed anywhere in the country.

Even partially built, the 16-square-mile reservoir is so big that it is impossible to see from one end to the other. The project also includes a 10-square-mile engineered wetland, or stormwater treatment area in the bureaucratic parlance of Everglades restoration, composed of lush vegetation that will serve as a natural water filter, with plant tissues absorbing nutrient pollution flowing from nearby farms.

Farther south, more stormwater treatment areas, 97 square miles of them in all, are scattered between the sugarcane and vegetable fields that make the EAA among the most bountiful regions in the nation and the fragile Everglades. Resembling nature but hardly natural, the wetlands are designed to replicate the filtering ability of the river of grass. The project, mandated under the Everglades Forever Act, which the state legislature approved in 1994, falls outside the scope of CERP, comprehensive as it is. Nowhere else on Earth have human-engineered wetlands like these ever been implemented at this scale.

Now the region faces another mounting threat. Temperatures and sea levels are rising and storm events are becoming more severe. The effort to rescue the river of grass has assumed an added responsibility: to save South Florida from the worst repercussions of climate change.

“If we don’t move on Everglades restoration, we’re not going to be able to address the issues and risks facing the built environment,” said Tom Van Lent, senior scientist at Friends of the Everglades, an advocacy group. “It’s more than just hope. It’s a necessity.”

A Pinball Machine of a River

The Everglades were formed from sea level rise. Over thousands of years, the tides built up the soil until it formed a gentle delineation between land and sea. The shallow freshwater coursed lazily among the sawgrass, the water stretching from the Atlantic Coastal Ridge to the east to the highlands of what is now part of the Big Cypress National Preserve to the west.

“The very mechanisms of sea level rise created the Everglades,” Van Lent said. “So we have to accelerate the efforts to get those back, because that’s what built the Everglades … but it’s not going to happen naturally. It’s probably too slow for that. But we have some tools, the very same tools you need to fight climate change or sea level rise.”

Today, one could characterize the river of grass as a series of lakes, or reservoirs if you want to acknowledge the entirely artificial aspect of the reservoirs’ existence. The Everglades have been divvied up into a series of components: the Kissimmee River to the north, whose bends have been straightened and restored to their natural condition; Lake Okeechobee, which has been fully contained by the Herbert Hoover Dike; stormwater treatment areas, which cleanse the water; and water conservation areas, which were constructed for flood control, water supply and recreation.

Like a ball passing through the barriers of a pinball machine, the water flows among the components as directed by 2,200 miles of canals, 2,100 miles of levees and berms, 84 pump stations and 778 water control structures. The infrastructure, its efficacy a marvel on such flat terrain, began with a desire to drain or “reclaim” the Everglades, converting backwater Florida into a sunny paradise of agriculture, growth and development. Later attention turned to flood control after a hurricane in the 1920s caused Lake Okeechobee to overflow, killing thousands.

The situation is not all that different from that along the Mississippi, Missouri or Tennessee rivers, where a series of dams controls water flow. Everglades restoration involves removing as many of these dams as possible without risking flood control, while adding more reservoirs for water storage, all to revive a river of grass that flows once more.

One of these water conservation areas, 164-square-mile Water Conservation Area 2A west of Fort Lauderdale, resembles what one might imagine the Everglades to be. The sunshine sparkles upon the ripples of the gently moving water, which is clear and colored like tea by natural plant tannins. Patches of sawgrass and cattails are interspersed among the shrubby bayhead willows. A shiny black anhinga dives for a fish. But signs of trouble abound.

In the past, water levels were managed at depths that were too high, which obliterated tree islands that served as important habitat for wildlife such as alligators and deer. To address the problem, water managers many years ago lowered the levels, but the tree islands never recovered, leaving ghosts of islands that lack the elevation to support the majestic hardwoods found in other parts of the Everglades, such as cypress, pond apple and pop ash trees.

“This is an example of one of our first disasters in the Everglades,” Van Lent said. He was pointing from an idle airboat on a particularly mild November morning toward a cluster of bayhead willows, a marker of one of the tree island ghosts.

Cattails in Water Conservation Area 2A west of Fort Lauderdale signal trouble in the Everglades. They are a sign of nutrient pollution from the sugarcane fields to the north. Credit: Iglesias/Miami Herald

Cattails are native to Florida, but in the Everglades they have been characterized as another tombstone, a sign that nutrient pollution from sugarcane farms to the north has transformed the ecosystem into something else. Fish populations have thinned; alligators have become scrawny.

“It looks beautiful, and the quiet is wonderful, but it’s not a very productive area,” Van Lent said. “The landscape you see here is a direct consequence of converting the Everglades, river of grass, into a lake.”

Everglades restoration is designed to solve these problems by lowering water levels in places like the water conservation area where levels have been too high and delivering water to locations where levels have been too low, such as Everglades National Park.

A lack of funding during the first five to seven years after CERP was signed into law slowed progress, but record federal and state funding in recent years has propelled the effort forward at an unprecedented pace. Projects are complete or under construction in nearly every region of the Everglades, according to a 2024 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, the most recent available. The National Academies, a private nonprofit organization, has issued biennial reports on the effort’s progress since 2004, under a congressional mandate.

One project and two major project components are complete, another is essentially finished and six are under construction, according to the report. Already, the river of grass is showing signs of improvement. The National Academies characterized increased flows into northeast Shark River Slough, part of Everglades National Park, as the “largest step yet toward restoring the hydrology and ecology of the central Everglades.” Investments in controlling invasive species have led to a 75 percent reduction in the area overtaken by melaleuca, a particularly thirsty tree species introduced in the river of grass near the turn of the 20th century to help drain it.

Reservoirs are located east and west of Lake Okeechobee and are intended to help protect the fragile estuaries from nutrient pollution and toxic algae. An area of wetlands the size of the District of Columbia, called the Picayune Strand, has been rehydrated. But CERP is only one notable restoration effort underway in the Everglades. A substantial restoration of the Kissimmee River is complete. Refurbishment of the dike around the lake is finished, and a revision of the lake management rules went into effect in 2024. Sections of the Tamiami Trail, a scenic highway that crosses the Everglades, have been elevated to allow water to flow.

“We’re really in a heyday of Everglades restoration,” said Paul Gray, science coordinator for Audubon Florida’s Everglades restoration program.

The work is not done. The river of grass remains highly compartmentalized, and more water storage is needed before additional dams can be removed without risking flood-control problems, Van Lent said.

“We’ve scaled back every opportunity to create storage,” he said.

A New Water Standard

Crucial to Everglades restoration is clean freshwater. Historically, the water’s purity was singular, giving life to a watershed that flourished because of a unique paucity of nutrients, a situation that hindered the pursuit of any single species that would dominate the rest.

This changed with the draining and containing of the Everglades and explosive growth and development that followed. The extensive waterworks also made way for sprawling sugarcane fields in the Everglades Agricultural Area, where farmers tended their crops with nutrient-rich fertilizers. The fertilizers engorged the Everglades on nutrients, especially phosphorus, leading to the widespread proliferation of cattails. By the late 1980s, the river of grass was at risk of becoming a river of cattails.

“We’ve always held the importance of water quality as paramount to any other issue,” said Curtis Osceola, senior policy advisor for the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, longtime environmental stewards for whom the Everglades are sacred. “For us it’s always been about keeping the water as pure as possible.”

Several years of bitter litigation between the federal and state governments over the farmers’ pollution led to the Everglades Forever Act, a historic plan to clean up the water based largely on the construction of the stormwater treatment areas. The farmers also pitched in with efforts of their own, including adjusting fertilizer methods, controlling soil erosion and increasing on-site water retention. The plan for the most part has been successful. Pollution has declined at more than twice the rate mandated by state law. Today, at least 90 percent of the water meets the state standard. The Everglades Forever Act focuses on water quality, while CERP, which came later, encompasses water quality, storage and flow.

Although Everglades restoration is now moving greater volumes of water south into fragile areas such as Everglades National Park, there are fresh concerns about the potential spread of phosphorus pollution.

This year, a new standard will take effect. Called the Water Quality-Based Effluent Limitation (WQBEL), the standard is designed to shift scrutiny from protected areas of the Everglades to the stormwater treatment areas. The standard also is poised to affect CERP projects, particularly the mammoth reservoir under construction in the Everglades Agricultural Area, a project Gov. Ron DeSantis has described as “the crown jewel of Everglades restoration.”

After its scheduled completion in 2029, the reservoir is projected to provide approximately 370,000 acre-feet of “new” freshwater, diverted from the network of canals that would carry the water out to sea. That amount is enough to flood 578 square miles with a foot of water. DeSantis, a Republican, has prioritized Everglades restoration and pushed to expedite the reservoir’s construction during his two terms in office. But under an agreement between the Army Corps and the South Florida Water Management District, the federal and state agencies overseeing Everglades restoration, water managers will not be able to operate the reservoir at full capacity until all stormwater treatment areas have demonstrated compliance with the WQBEL for at least five years.

As recently as 2024 only one stormwater treatment area met the standard, according to the National Academies. In 2022, the scientists said meeting the WQBEL by 2027 would be a “significant challenge,” although they noted phosphorus levels in the stormwater treatment areas were trending in the right direction. Noncompliance with the new standard would affect how much water could flow south into the reservoir, following the river of grass’ historic path, rather than east and west, threatening the estuaries that have been hammered by toxic algae, an issue that was central to DeSantis’ 2018 gubernatorial campaign.

“Fundamentally there is no Everglades restoration unless the water is clean,” said Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades. She said if the reservoir “can’t effectively hold and flow as much water as was promised to the public then that raises very serious questions about whether the public has been served by the project.”

Friends of the Everglades and other groups, such as the Sierra Club in Florida, have raised concerns about the reservoir’s design, which they say does not meet restoration requirements. The organizations have voiced reservations about water quality and whether the reservoir will deliver enough water south. The groups also say the project’s designers failed to factor in the consequences of climate change. Friends of the Everglades is pushing for 160 square miles of additional conservation land in the Everglades Agricultural Area, to create space for 1 million more acre-feet of water storage.

“All of the other projects in most cases are, for me, mitigation,” said Cris Costello, senior organizing manager at the Sierra Club in Florida. “ I don’t think anybody, any of us, the organizations and the people in the state of Florida who embarked on this road 25 years ago, thought that CERP would become mitigation projects rather than actual restoration.”

Estenoz, a former assistant secretary for fish and wildlife and parks in the Biden administration before joining the Everglades Foundation, said operating the reservoir at less than its full capacity would not be an option, but she believes water quality standards, including the WQBEL, would be met.

“They have to be met. That’s the commitment,” she said. “It’s not an acceptable outcome that, ‘We’re done. We don’t meet the water quality standards therefore hydrology projects can’t be operated.’ That’s not the way the program is set up.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowEverglades restoration has always enjoyed remarkable bipartisan support, but like other environmental programs under the second Trump administration the effort has faced new challenges. One such development was the hastily assembled Everglades detention site called Alligator Alcatraz, where the Trump administration incarcerated thousands of undocumented migrants.

The facility’s existence alongside protected lands perpetually leased to the Miccosukee Tribe and are part of the Big Cypress National Preserve tested federal policies, including the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Environmental groups and the tribe are pursuing litigation against the federal and state governments over the site, which the groups say was rushed to completion without any opportunity for public comment or environmental review as required by NEPA. The government agencies say the site does not threaten the environment.

“Alligator Alcatraz is perhaps the most stark example of the administration’s disregard for this fabric of environmental protections that were woven together a half-century ago, but it certainly doesn’t stand alone,” said Samples of Friends of the Everglades, one of the groups involved in the litigation. “If we continue to see an attack on NEPA it could affect things like Everglades restoration projects themselves, which have to comply with the NEPA process.”

What Comes After

Already there are spots where the Everglades are slipping away into the rising seas. The soil is collapsing, leaving something resembling large puddles among the freshwater marshes.

“It’s like Swiss cheese, round-type holes in the landscape that are filled with water,” said Steve Davis, chief science officer at the Everglades Foundation. “The rate of loss is very rapid. It’s on the order of a decade or two that these wetlands can be lost.”

The river of grass is vulnerable to climate change in various ways. Rising temperatures increase evaporation, further stressing a watershed already under pressure from growth and development. The hotter temperatures are sparking changes in precipitation—rainier rains and drier droughts. The watershed also is situated on relatively flat, low-lying and porous terrain, enabling higher tides to penetrate deeper into the freshwater marshes through the vast network of canals that holds the watershed together.

The National Academies, in its 2024 report, called for a strategy to understand how climate change may affect the massive effort to restore the Everglades. The report suggested developing a series of projected scenarios, based on variables such as hotter temperatures and rising seas, to layer with the models used to plan projects. The scenarios would help planners identify vulnerabilities that could affect the wildlife and habitats the projects are meant to preserve. Davis said it was too soon to cede South Florida to the rising seas.

“That notion of just throwing in the towel and giving up on Florida is really kind of reckless, because there is so much and so many that depend and will continue to depend on this system for decades to come,” Davis said.

Everglades restoration can help fortify the region as the climate warms by carving out space for more freshwater to remain on the landscape. That would encourage new peat accumulation and carbon sequestration.

But for all the billions of dollars spent, all the bipartisan support and dirt bulldozed, the grand gesture of hope may not be enough to fully address South Florida’s complex predicament, which begins with population growth that continues to stress the natural resources vital to sustaining that development, at a time when climate change is poised to further complicate the region’s plight. As profound as the hopeful gesture has been, Van Lent said another will likely be necessary once this one is deemed complete.

“The question becomes, what comes after CERP? What do we have to do so that we can really address the actual problems that South Florida faces?” he asked.

“How do we supply enough water to everybody? How do we maintain and improve the ecological function of the Everglades? All those things are important to our future, and CERP was never designed to cover them all,” he said. “It was never designed to really handle large-scale problems like ecosystem restoration or climate change. It’s designed to boil it down into very small, discrete doable project elements, and that’s not going to get us where we need to be.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,