BOISE, Idaho—Ping.

The sound that wrenched Lucian Davis awake was a phone notification from the wildfire-tracking app Watch Duty. There was a fire just a few miles downslope from the tent where he had been sleeping.

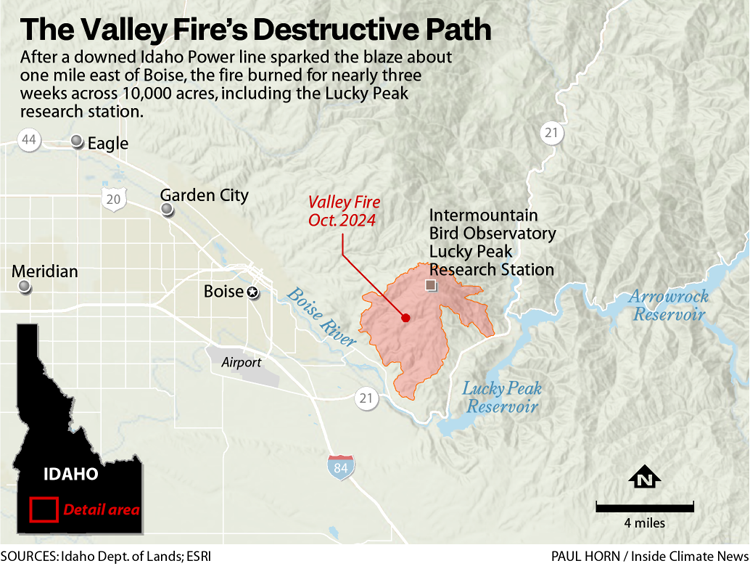

Davis was the lead bander at the Lucky Peak station, a research site run by Boise State University’s Intermountain Bird Observatory (IBO) near the school’s namesake city. It sits within a small patch of mountaintop scrub and Douglas fir forest, surrounded on nearly all sides by sagebrush steppe. Each fall, the station hosts seasonal field technicians who study the songbirds, raptors and owls that stop at the island of habitat in a sea of open country.

But on October 4, 2024, that open country was burning. At 6:15 that morning, when the alert awakened Davis, the fire was climbing toward the research station, where eight technicians and a class of 6th graders on an overnight school trip were camping.

The teachers woke their kids and got them onto the bus, but as they were driving down the mountain, the fire jumped the main road. Flames licked the sides of the bus, but the students and teachers made it out unharmed.

Meanwhile, the station’s crew grabbed their data sheets and piled into their cars, leaving their tents and gear behind. With fire surrounding the main road, they bounced down an unmaintained back route and made it to safety by 8:30 a.m.

From Boise, the crew watched the blaze creep up the mountain as ash speckled their cars.

“For like an hour or two, we couldn’t see the top at all from in town. It was just totally obscured by all the smoke,” Davis said. “Then, when we could actually see it, I was like, ‘Oh shit.’”

Even from the base of the mountain, the crew could see that the peak’s trees were bare and blackened. It was clear the fire had reached the station.

The Valley Fire lasted for three weeks and burned more than 10,000 acres, including about half of the bird research station’s grounds. The fire melted research equipment, destroyed nearly all of the technicians’ camping gear and personal possessions and turned the blind from which the crew studied raptors, which was graffitied with 30 years of researchers’ drawings and signatures, to ash.

But while devastating to the station’s staff, the fire also presented a rare research opportunity.

No bird research station had ever been impacted by a wildfire like this, so detailed studies of how a blaze would impact the animals and their habitats is hard to come by. Lucky Peak, meanwhile, has 30 years of data on its birds from before the fire. By collecting comparable data after the blaze, they could investigate aspects of fire ecology that were nearly impossible to study before.

But while fire is a natural and healthy component of an ecosystem, the Valley Fire didn’t happen in a vacuum. Invasive grasses downslope likely made the fire spread faster, said retired Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management fire ecologist Louisa Evers, who volunteers with IBO, and climate-driven drought may have stoked it. Now, the hotter climate and invasive plants will likely shape the way that the peak regrows. So regardless of how the birds of Lucky Peak respond to the fire, their habitat may never be the same.

Some Birds Rise, and Others Fall

Nearly a year after the fire, the road up Lucky Peak was still lined with charred bitterbrush and the husks of burned trees filled the hillside behind the station. The slope that once hosted the crew’s camp was barren and ashy, the site speckled with hunks of melted plastic from tents and sleeping bags.

But the station’s laboratory, housed in a yurt, and its kitchen tent survived mostly unscathed, as did some areas of thicket and Douglas fir forest.

“I was worried it was going to be totally nuked,” said Heidi Ware Carlisle, education director at IBO. “The views were sort of whiplash. In a single photo, it can look totally fine or totally terrible.”

In some ways, it was the best case scenario, she said. The fire created a mixture of old habitat with young shrubs and wildflowers between them, which with time will likely improve the productivity and diversity of the ecosystem.

Mornings on the peak progressed through the fall as they did before the fire. At sunrise, the crew opens up a series of “mist nets”—ultra-fine netting stretched between two aluminum poles. Every half hour, they go and check what birds flew into the nets, extract them and bring them back to the lab.

There, a designated bird bander attaches an aluminum cuff with a unique nine-digit code to each bird’s leg and runs it through a series of measurements: wing length, tail length, age, sex, fat content, muscle size, parasite load. The results are stated as a series of letters and numbers that another researcher transcribes. After a few minutes, the bander releases the befuddled bird with a new anklet.

Before the fire, this data helped illuminate how important this montane forest habitat is for migrating songbirds, said Jay Carlisle, research director at IBO, and Heidi’s husband. Now, it will also provide a point of comparison for data gathered since the fire.

Some changes are already obvious. After the blaze, rock wrens and lark sparrows, both open-country birds, nested on the peak for the first time on record. A pair of Lewis’s woodpeckers excavated a nest cavity in a burned tree. Lazuli buntings, which rely on new growth, have boomed in the surge of vegetation that followed the fire.

But for other birds, the fire was a serious hit. During summer banding, the crew caught fewer forest birds like dusky flycatchers and Nashville warblers.

The new sightings and population declines reflect these birds’ well-known habitat preferences, Heidi noted. The most useful insights that Lucky Peak can provide will come from the data the researchers collect while banding—fat stores, age ratios, whether individual birds return after the fire, said Richard Hutto, University of Montana professor emeritus who studies avian fire ecology and is not involved with the bird observatory. “That kind of thing you’d never get out of basic surveys,” Hutto said.

While only preliminary, the data from last summer’s breeding season paints a picture of a struggling bird community. They carried less fat than before. Their wing muscles were weaker. Their bodies carried more blood-sucking flat flies. Jay also noted that, while catching 40-80 birds a day used to be typical in the early autumn, 30-40 birds was considered a good number this fall.

Songbird technician Tyler Jensen also noted that local nesting birds weren’t sticking around to raise their young. “The birds just basically disappear as soon as the fledglings can fly,” he said. Young birds were also scarce in mid-July, when the station’s nets are typically full of just-hatched fledgelings, possibly because the juveniles left with their parents, or, more likely, because most nests on the peak failed to produce any youngsters.

This summer, banding revealed another trend. During 2023 and 2024, about 15 percent of the birds that they captured during the breeding season were at least two years old. This year, that number was around 35 percent.

Heidi hypothesizes that the banding area has some of the peak’s best remaining habitat, so these older adults concentrate there and push the younger birds out. Or the older birds may return because they nested there before the fire while the younger birds don’t find any of the remaining habitat well-suited to them and head elsewhere.

As birds migrate in the fall, research at Lucky Peak can show how they use the freshly burned habitat, a subject that has barely been researched at all, Hutto said. When it comes to fire, “there’s some neat biology that goes on during the nonbreeding season, and very little published on [it].”

Later in the fall, owl banders and hawkwatchers joined the crew to collect data that may help clarify how those birds respond to fire.

Despite these short-term changes, Evers noted that the fire probably benefited the peak’s forests by burning through trees impacted by parasitic dwarf mistletoe and encouraging new growth.

Fire is an important and natural component of nearly every ecosystem, Hutto stressed, even when it is a dramatic disturbance or has short-term negative effects. Without a natural fire cycle, he said, there would be no scrub, no fields, no young forests and no habitat for the vast majority of birds.

But climate change and invasive species are disrupting that cycle.

Invasive Grasses Flourish in Fire, Displacing Critical Sagebrush Habitat

“From here, you can see perfectly the problem.”

Ann Moser is standing at the archery range a few miles downslope of the Lucky Peak research station. Nearly all of the landscape here, which was once a sagebrush steppe, was burned.

One small section of the hillside is covered in native yellow bunchgrasses. This, she explains, is what would typically spring up after a fire—their deep roots nourish the soil and preserve its moisture for the bitterbrush and sagebrush that follows.

The rest of the hillside is carpeted in thick green grasses. “Rush skeletonweed,” she said.

Rush skeletonweed is one of two particularly problematic plants for Moser who, as a wildlife biologist for Idaho Fish and Game, is watching over Lucky Peak’s recovery. Cheatgrass is the other. Both plants are invasive species from Eurasia, and both seem primed to change the cycle of fire on the mountain.

Cheatgrass and rush skeletonweed germinate in late fall, when most other plants are dormant, and grow through the winter, their short roots sucking the moisture out of the topsoil. Come spring, they die, shedding their seeds and creating a thick layer of what firefighters call “fine fuel” that ignites easily and burns fast. If a fire comes, the grasses’ seeds have evolved to survive it and germinate quickly, so the invasives can absorb all the fresh nutrients in the soil before other plants have a chance to grow.

The grasses have been present at the base of Lucky Peak for a while, but the Valley Fire supercharged their growth.

“The whole front range facing the town of Boise is all south facing,” Moser said, noting the invasive grasses do best on slopes with that aspect. “It’s hot and dry, and it’s going to be the hardest part to recover.”

Moser’s team from Idaho Fish and Game and the federal Bureau of Land Management began recovery work soon after the fire. They dropped thousands of sagebrush seeds from a helicopter and planted 52,000 seedlings of native trees on the slope. Later in the fall, they planted another 60,000 plants. “We’re trying to get as much stuff on the landscape as soon as we can to give it a chance to outcompete the cheatgrass,” she said.

To control the invasives themselves, the only option is herbicide, she said. That’s an extreme option, she acknowledged, even though the teams use carefully chosen products, spray minimally and restrict their spraying to the fall when most native plants are dormant. “I don’t know what its effect is going to [have] on the lupin, for example,” she said.

It’s hard to know how successful this restoration will be. High-altitude sagebrush should only burn every 10-300 years, and these burns should be patchy, Moser said, to allow neighboring sagebrush plants to reseed the burned patches. But the invasive grasses carpet landscapes in what firefighters call a “continuous fuel bed,” which after a fire can build up and burn again in as little as one or two years, Moser said. Any subsequent fire driven by the invasives could undo all of Moser’s work.

“I can argue to some extent the fire was beneficial in the trees,” she said of the nearby forests, which can show improved health after wildfires. “I don’t think I could argue that it was beneficial here.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowFor the forest around the research station, cheatgrass and rush skeletonweed could pose an existential threat. Cooler temperatures and heavier winter snowpack have kept the invasives rare at the peak, but with climate change making winters milder and weather growing hotter and drier, that may soon change. Though there is scholarly disagreement on how often and intensely these forests should burn, the historic frequency was certainly less than that of cheatgrass and rush skeletonweed. If these grasses colonize the peak, they could establish a new fire cycle of more frequent, faster, higher severity fires that would slowly but surely burn away the forest.

Climate change could impede Lucky Peak’s recovery more directly, too. Previous research has found that Douglas fir and ponderosa pine forests struggle to regrow after burns in today’s climate-altered world. Without the shade from these trees, invasive grasses have another advantage in their march up the peak.

“We’re on a sinking island, basically,” Heidi said of the steady rise of warmth and aridity up the mountain. “When is it going to flood?”

“It’s Never Gonna Be the Same”

For Davis and Jensen, the biggest loss was the slope above the bird banding station where technicians camped each fall. When it was covered with Douglas firs, Jensen found it homey, cozy and full of birds.

The fire killed every fir on that slope, and Idaho Fish and Game cut down their skeletons, leaving stumps and ashy earth behind.

“I really miss it,” Jensen said. “It’s never gonna be the same without constant nuthatch babble above the tents.”

The technicians whose equipment burned suffered a real loss, Heidi said, while she and Jay live in Boise and didn’t lose anything tangible in the fire. But she still feels grief for the mountain.

“A lot of my sadness comes from the personal part of it,” she said.

The couple met there in 2005, when Heidi was a volunteer for the songbird banding project that Jay started, and they both did their graduate thesis research at the observatory. In 2017, Jay proposed to Heidi there. They regularly take day trips with their kids to the peak. Their eldest son is named Felix—Latin for lucky.

Heidi knows that the burnt Douglas fir groves won’t regrow in her lifetime, and she laments that her children won’t remember the peak the way she and Jay do. She tears up remembering the days of uncertainty right after the fire, when no one knew if the station had survived.

“What’s keeping me going is the science stuff,” she said.

Heidi sees two possible futures for Lucky Peak. In one, the Valley Fire is only the first of many blazes as climate change and invasives crank up the frequency of fire in the forest, which helps the grasses take over. A temporary disturbance becomes a permanent change.

But there’s another future, a narrow path in which well-timed rains, effective invasive species management and a bit of luck keep fires at bay while native vegetation regrows. In this scenario, Heidi suspects much of the burn would turn into lush thickets of deciduous shrubs. If humanity can curb climate change, the coniferous forests that the staff remember would eventually return, too, perhaps with the slightly more climate-tolerant ponderosa pines as the dominant species. One day, many years from now, it would burn again, as it naturally should.

And for as long as they possibly can, observatory staff will be there, studying how birds are responding to whatever change comes.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,