The Trump administration’s new dietary guidelines, released Wednesday, take a dramatic turn toward encouraging the consumption of animal protein, including red meat, something a growing number of governments and international reports in recent years have urged consumers to reduce for both health and climatic reasons.

The new advice says to “prioritize protein at every meal,” while the accompanying graphic—a revised and resurrected “food pyramid” designed as a handy visual reference—includes an outsized steak at the top. And, for the first time, despite medical warnings, the government suggests consumers use beef tallow for cooking, a personal preference of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr.

In developing and publishing the new guidelines, the administration, in an unprecedented move, dismissed the traditional advisory process. Instead, it published a scientific “foundation” document that both critiqued and ignored the recommendations of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, the group of expert nutritionists that informs the guidelines. A majority of the document’s authors acknowledged receiving funding from the meat and dairy industries.

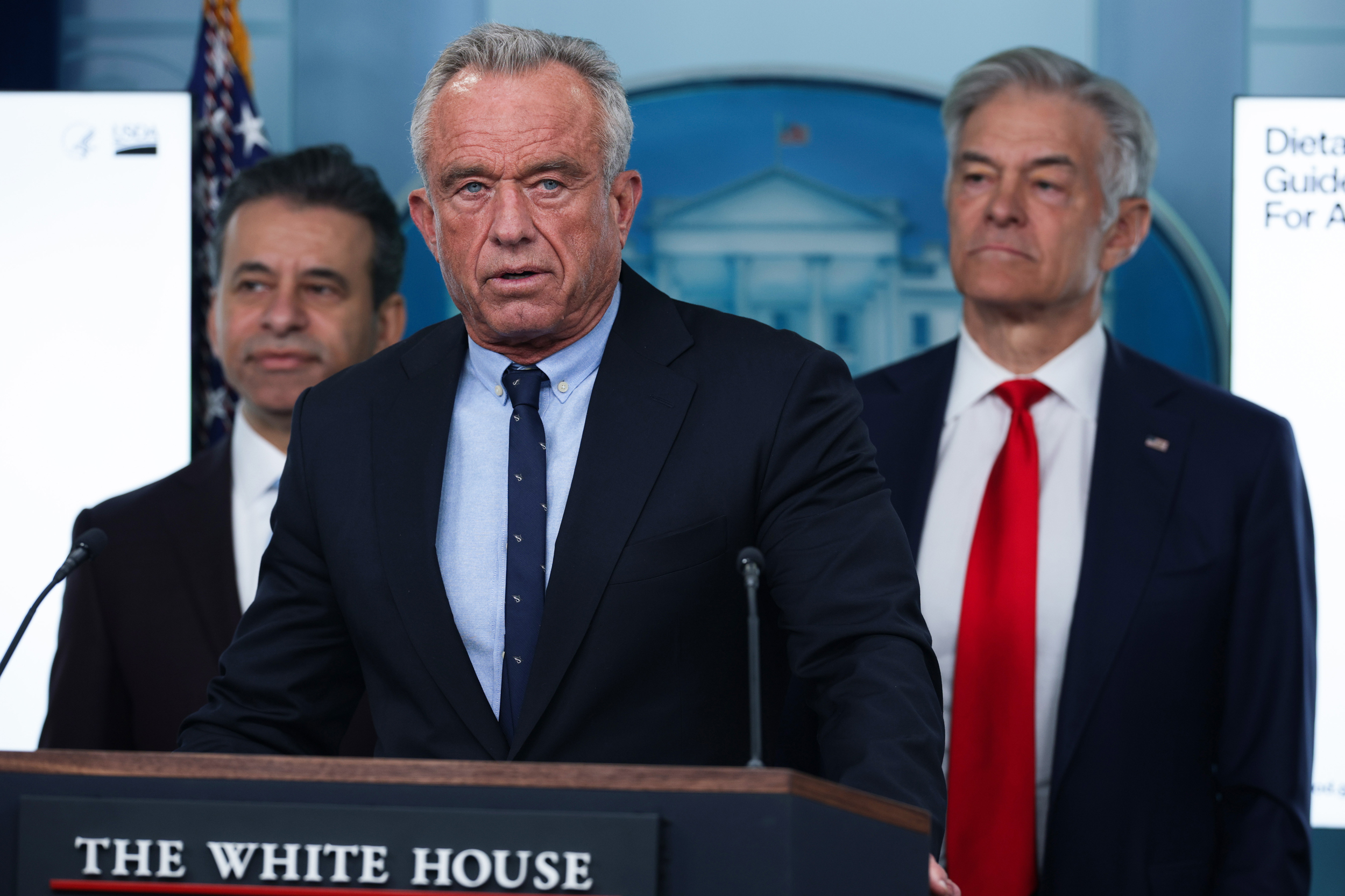

The meat industry celebrated the new guidelines, which Kennedy and Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins called “the most significant reset of federal nutrition policy in decades.” Health and environmental advocacy groups called them a dangerous reversal of science-based health advice that could worsen the climate and ecological impacts of livestock.

“Americans already get too much protein. We don’t need to be reminded to prioritize protein,” said Scott Faber, a senior vice president of government affairs for the Environmental Working Group. “We do need to be encouraged to get some of our proteins from plants.”

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans, published every five years by the departments of Health and Human Services and Agriculture, is a sweeping document that shapes how Americans eat, how the government spends $40 billion on food and nutrition programs and how the roughly $2 trillion food industry produces and markets foods to consumers.

The lengthy process of developing the guidelines is often fraught and political as various industry groups scramble to ensure their product gets the government’s stamp of approval—or, more importantly, isn’t singled out as a nutritional villain.

Red meat and dairy products have been among the most contentiously debated for decades, largely because of their fat content, which has been linked to cardiovascular disease and some cancers. In recent years, the advisory committee that develops the guidelines has also weighed issues of environmental sustainability, adding more complexity to the debate.

These discussions have emerged as more research clearly demonstrates that greenhouse gas emissions from the production of livestock, especially cattle, are a major contributor to the climate crisis. Agriculture in the U.S. accounts for about 10 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions, and nearly half of that comes from cattle belches and manure. Globally, livestock agriculture’s share of emissions is between 6 percent and 14.5 percent, depending on the estimate.

Major international reports, including from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, have urged consumers, especially in developed countries, to cut down on red meat and dairy consumption to help slow livestock-related emissions. Research has found that it will be impossible to reach global climate goals—even if radical cuts are made to fossil fuels—without major reductions in global livestock consumption.

Most of the world’s largest economies now account for this and include sustainability considerations in their dietary advice.

But not the U.S.—which consumes more beef in total than any other country. (Per capita, U.S. consumers eat about 82 pounds of beef a year, behind Argentina—108 pounds—and Brazil—86 pounds.) The country has historically produced the most beef, until last year, when Brazil overtook U.S. production for the first time.

Nutritionists on previous advisory committees have tried—and failed—to include environmental considerations in the guidelines. In 2015 the committee included in the scientific report that underpins the guidelines a recommendation to eat less livestock-based food because of its heavy environmental toll, but the language was stripped out of the final guidelines by the Obama administration.

The 2020 advisory committee also considered the questions of sustainability but never developed formal advice. The most recent advisory committee, which was formed under the Biden administration, did not consider sustainability directly but did encourage consumption of more plant-based proteins.

“The health science was pointing toward prioritizing plant-rich diets, plant-based sources, over animal-based sources of protein, especially beans, peas and lentils, and to reduce red and processed meat,” said Leah Kelly, a food and agriculture specialist with the Center for Biological Diversity who has tracked the guideline development process. “That all aligns with a more sustainable diet.”

The meat industry immediately attacked the committee’s report, which was published in late 2024.

After the Trump administration took office early in 2025, the report—based on the expert advice of 20 committee members, multiple hearings and extensive public input— was sidelined in favor of Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again agenda.

“They basically said they were going to throw it out the window,” Kelly said.

Instead, the new guidelines were largely underpinned by an unprecedented new document, “The Scientific Foundation for the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” which was published along with the guidelines this week.

“This other report had no public input, no transparency,” Kelly said. “They never talked about it all year when they could have. They didn’t call for public comment. They didn’t do any of that. They just privately, secretly consulted these supposed other nutrition experts.”

When asked why the agency did not allow public review of the new foundation document, a spokesperson for the USDA wrote in an email: “Expert reviewers conducted systematic reviews, umbrella reviews, and comprehensive literature syntheses. Evidence was evaluated based solely on scientific rigor, study design, consistency of findings, and biological plausibility. All reviews underwent internal quality checks to ensure accuracy, coherence, and methodological consistency.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowFive of the nine authors of the new document acknowledged that they have received funding from the beef and dairy industries in the past, including from the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, the country’s biggest beef lobby.

While the document says the experts were screened for bias, new research suggests that beef-industry funded science clearly favors conclusions that support the healthful—or at least not unhealthful—attributes of meat consumption. The meat industry has similarly worked to downplay the climate impacts of livestock consumption.

The new document says that in order to “conduct this supplemental scientific analysis, nutrition scientists and subject matter experts were selected through a federal contracting process based on demonstrated expertise.”

Those experts criticized the advisory committee’s emphasis on plant-based protein, saying it “consistently advocated plant-based dietary patterns, deprioritized animal-sourced proteins, and favored high linoleic acid vegetable oils” and that its proposal to prioritize “beans, peas, and lentils while listing meats, poultry, and eggs last” was “a symbolic reordering lacking scientific justification.”

For some health advocates the new guidelines have some bright spots, including a recommendation to reduce consumption of highly processed foods—a favored target of Kennedy’s. That, however, is not sitting well with some agricultural industry groups, including the Corn Refiners Association, which represents processors of high fructose corn syrup and corn oil.

“For the first time in 40 years, the Dietary Guidelines for Americans have disregarded the scientific report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee,” said John Bode, the association’s president and CEO. “This deviation from past practice undermines both the credibility and scientific foundation of the Dietary Guidelines.”

The guidelines also maintain the government’s longstanding recommendation to limit saturated fats to 10 percent of daily calorie intake. Many health and environmental advocacy groups were concerned the percentage might be raised, given Kennedy’s praise for beef tallow and dislike of seed-based oils.

Kennedy said Wednesday the new guidelines would “end the war” on saturated fats, which come mostly from animal sources.

“They kept the saturated fat limit, but everything else in the document seems to point to increasing saturated fat, because if you’re increasing meat and dairy, those are the foods highest in saturated fats,” Kelly said. “It’s kind of self-contradictory.”

Emily Hilliard, a press secretary for the Department of Health and Human Services, responded to this point, saying “there is significant academic disagreement” on the limit for saturated fat.

“It was our goal for this report to not be ‘activist’ – and only make statements that are widely accepted by the latest nutritional research,” Hilliard wrote in an email. “ While modifying the protein recommendation falls in the scientific recommendation, changing the saturated fat cap would not.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,