Several annual international climate reports released Tuesday indicate that relentless human-caused warming continued in 2025, especially in the oceans and at the poles.

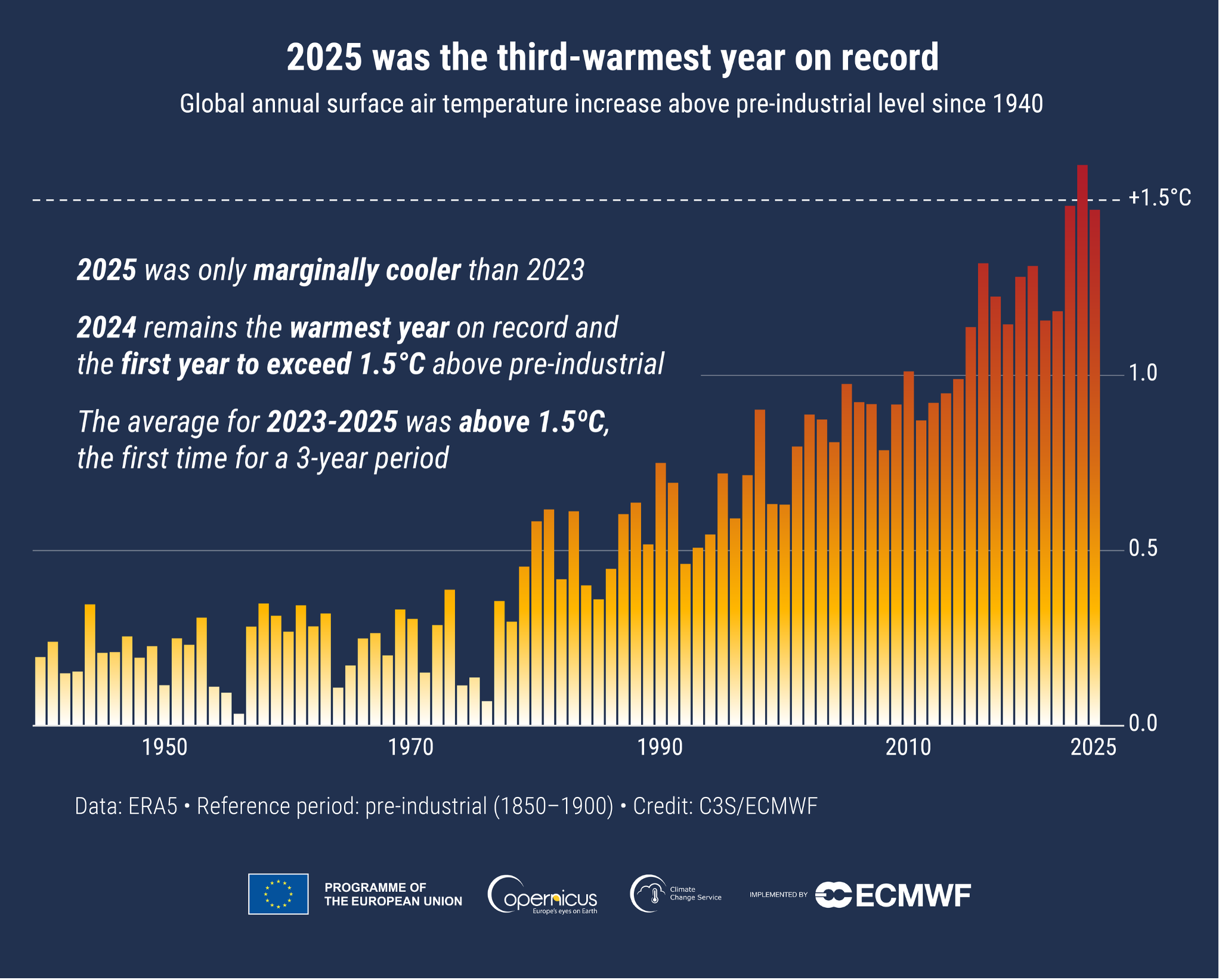

For the third year in a row, Earth’s average temperature ran close to 1.5 degrees Celsius hotter than the climate that sustained human civilizations as the 20th century began, before fossil-fuel pollution started damaging the atmosphere.

Avoiding more than that level of warming is also the key long-term temperature goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement. Research shows that warming by more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above the baseline will spell the end of nearly all global glaciers and coral reefs and mark a dangerous red zone for damage and destruction of ecosystems, food supplies, human health and infrastructure.

The European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service report released Tuesday ranked 2025 as the third-warmest year on record, just a hair cooler than 2023 and within striking distance of 2024, the hottest year on record. Together, the past three years averaged more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures, the first time any three-year stretch has crossed that threshold.

“Exceeding a three-year average of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels is a milestone none of us wished to reach,” said Mauro Facchini, head of earth observation at the European Commission’s directorate general for defense industry and space.

The report reinforces the importance of Europe’s leadership in climate monitoring to inform both mitigation and adaptation, he added. The U.S. is rapidly pulling back amid Trump administration attacks on climate science.

Global temperatures from 2023 to 2025 suggest that the past warming rate is no longer a reliable predictor of the future, said Kristen Sissener, executive director of Berkeley Earth, an nonprofit climate research organization that also released a global report Tuesday.

“The warming spike of the past three years underscores how quickly the climate system can change, and how essential sustained monitoring is to understanding those changes in real time,” she said. “Continued investment in high-quality, resilient and robust open climate data is critical to ensuring that governments, industry and local communities can respond based on evidence, not assumptions.”

At today’s pace of emissions, Copernicus scientists said, the world is on track to hit the Paris Agreement’s 1.5-degree Celsius limit permanently by the end of this decade, sooner than expected when the deal was signed.

“Emissions simply haven’t come down as fast as people believed they would,” Samantha Burgess, deputy director of Copernicus, said when asked about crossing the Paris Agreement limit so soon. “That’s the big difference between where we thought the world would be in 2015, and where we are now.”

And the extreme temperatures of 2023, 2024 and 2025 will be seen as cooler than average in just a few years, Burgess said, warning that continued fossil-fuel emissions are rapidly resetting what the world considers normal.

Faster Warming Likely Ahead

The Copernicus report was foreshadowed by a Dec. 18 analysis of recent temperature trends by noted climate scientist James Hansen and colleagues. They found that 2025 stayed near or above the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold even after the strong planet-warming El Niño weather pattern of 2023–2024 eased.

And they projected that a new El Niño could push global warming to about 1.7 degrees Celsius in 2027. El Niño is a Pacific Ocean temperature cycle that alternately warms or cools the entire planet by 0.1 to 0.2 degrees.

“These three years stand apart from those that came before,” Samantha Burgess told reporters at a media briefing Monday, noting that record-high ocean temperatures are now persisting even without a strong El Niño influence.

“By far and away, the high global temperatures of the last three years have been due to the record amount of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere,” Burgess said. Other factors can have regional impacts, such as reductions in industrial and shipping pollution that reflect heat away from Earth, especially over oceans, and can also nudge the global average by about 0.1 degrees Celsius.

Major climate monitoring centers around the world are releasing their annual assessments in coordinated fashion Tuesday and into early Wednesday, including the World Meteorological Organization, NASA and the United Kingdom’s Met Office.

The reports’ exact global temperature figures differ by a few tenths of a degree, reflecting slightly different datasets and analytical methods, but they all point in the same direction: Global warming is accelerating, driven overwhelmingly by human emissions.

“We’re all very consistent in the near term, because our planet is better observed than it has ever been,” said Burgess.

Their synchronized release demonstrates that science and data speak for themselves. Even at a time when scientific institutions face extraordinary ideological attacks, the world’s leading climate agencies are allowing the measurements to define the reality of a rapidly warming planet.

“These three years stand apart from those that came before.”

— Samantha Burgess, Copernicus

A separate analysis released last week by Climate Central quantifies the damage caused by climate extremes in the United States. The group found that the country experienced 23 weather and climate disasters in 2025, from destructive storms and floods to heat-driven wildfires, that each caused at least $1 billion in damage, totaling about $115 billion in losses.

Climate Central is a nonprofit organization of scientists and journalists that researches and communicates climate science and impacts. After the Trump administration cut NOAA’s billion-dollar disaster database, the group revived it to keep long-term loss tracking publicly available using the same scientific methods.

In addition to the disaster database, the Trump administration last year reduced weather balloon launches, said it would shut down the National Center for Atmospheric Research and cut thousands of positions at science-focused agencies. Experts warn that weakening or sidelining science leaves communities more vulnerable.

Several groups of former federal scientists are working outside the government to ensure critical information continues to flow. The American Meteorological Society and the American Geophysical Union are teaming up to publish a series of peer-reviewed papers to help fill the gap left by the discontinuation of the National Climate Assessment. Other former federal officials are building Climate.us as a replacement for a federal website that the Trump administration shut down last year.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowAsked about the potential impact of cuts to U.S. climate science programs, Carlo Buontempo, director of the Copernicus Climate Change Service, emphasized that the global climate record does not belong to any single nation, and that the greatest risk lies not in past data, but in future gaps. The international observation system goes far beyond data gathered by the United States, he added.

“Global data observations are essential to efforts to confront climate change and air quality challenges,” said Florian Pappenberger, who leads the forecast and services department as deputy director-general of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.

“These challenges don’t know any borders,” he said. “They don’t know what language is spoken underneath them, and therefore, it’s, of course, concerning that we have an issue in terms of data.”

Polar regions played an outsized role in driving global temperatures higher last year. Antarctica experienced its warmest year on record, while the Arctic had its second-warmest year, a pattern scientists attribute to feedback loops associated with sea-ice loss and, in Antarctica’s case, a rare atmospheric disruption that spiked surface temperatures.

In February, the combined sea-ice cover of both poles fell to the lowest level observed in the satellite era, underscoring how quickly the planet’s reflective ice shield is shrinking.

Extreme heat is increasingly how people experience that global warming signal. Copernicus reported that about half of the world’s land surface experienced more days than usual with dangerous heat stress in 2025, conditions that strain the human body. Scientists warned that while no single heat wave or wildfire can be attributed solely to climate change, the background warming is making such extremes more intense, more frequent and more disruptive in a preview of what will become more common as the planet moves deeper into Paris Agreement overshoot territory.

For the contiguous U.S., 2025 was the fourth-warmest year on record, according to the annual State of the Climate report from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, also published Tuesday. The NOAA report highlights that heat was concentrated in the West, with Nevada and Utah recording their warmest years in the 134-year record. As part of that report, the U.S. Climate Extremes Index ranked 2025 as the 12th-highest on record, particularly for maximum and minimum temperatures and for dry conditions.

Climate Extremes Affect Energy

In a separate report Tuesday, the World Meteorological Organization warned that rising temperatures and climate extremes are reshaping electricity demand and energy-system risks worldwide, as hotter summers drive surging cooling demand while drought, heat waves and wildfires threaten power generation, transmission lines and fuel supply chains.

The report, produced with the International Renewable Energy Agency, found that climate extremes are increasingly disrupting both renewable and conventional energy systems, including drought-stressed hydropower plants and strained grids during hot spells.

Together, the findings underscore that climate change is no longer just an emissions problem but an operational risk for energy systems, which will increasingly shape how power grids are designed, protected and modernized as the world warms even further.

Copernicus’ Buontempo said that, with the inevitability of passing the 1.5-degree mark of the Paris Agreement, “it’s up to us to decide how we want to deal with the higher risks that we’ll face as a consequence.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,