At the narrow entrance to Sequim Bay’s tidal channel, an underwater, four-bladed turbine spinning above the seabed might look like a hazard. But here, in Washington state, underwater acoustic cameras bring to life a different story: Schools of Pacific herring swim through the rotors; harbor seals stop and curiously approach; diving cormorants instinctively steer clear.

An analysis of 1,044 unique interactions between marine life and this small-scale tidal turbine found zero collisions for seals or seabirds, and a 98 percent safety rate for fish, according to a study by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, whose facility overlooks the high-flow test site.

While the U.S. Department of Energy estimates tidal energy could power 21 million homes, the industry has been paralyzed by a lack of safety data. The report, released Wednesday, provides first-of-its-kind data for North America and could help unlock the regulatory stalemate holding back tidal energy.

“The risk for collisions is low,” said Christopher Bassett, a co-author and research scientist at the University of Washington, referencing underwater impacts on marine life. Harbor seals, with their distinctive dog-like snouts, were “clearly in control and avoided making impact with the turbine.”

Although tidal energy has the potential to provide a carbon-free source of power with complete predictability, U.S. progress has been slow. Unlike South Korea’s Sihwa Lake Tidal Power Station—which can power a city of 500,000—American equivalents, such as the San Francisco Bay Tidal Energy Project, rarely make it past permitting. Critics claim tidal turbines act as underwater blenders for marine life and, without empirical data to prove otherwise, U.S. regulators have historically defaulted to caution.

“The limited number of long-term turbine deployments has meant there is a lack of site-specific data to fully assess potential environmental impacts,” said Elisa Obermann, executive director of Marine Renewables Canada. This has created challenges for industry and regulators alike. “Findings from long-term research showing no collisions between marine life and tidal technology are a positive milestone for the industry and a significant step forward,” she said, about the 109 days of aquatic analysis.

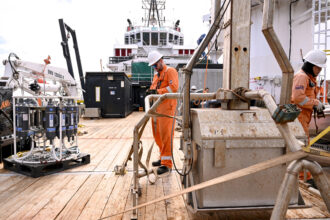

The research, funded in part by the Naval Facilities Engineering and Expeditionary Warfare Center, offers new insights into underwater animal activity using AI-driven software. The technology was trained to ignore drifting debris and used strobe lights to help capture photos only when silhouettes were detected, offering a rare look at behavior in total darkness.

Ninety-two seal interactions were observed day and night. The marine mammals displayed “strong swimming capabilities indicating that they are capable of evading collision,” according to the report. Pigeon guillemots and double-crested cormorants were observed on 406 occasions, most frequently foraging at high tide when the turbine was not naturally operating. Neither a single bird nor seal collided with the turbine in almost four months of observation.

Meanwhile, 224 individual fish and five schools encountered the turbine. Just four fish were hit, and three of those continued swimming, suggesting contact was not always fatal. The machine learning software also identified kelp crabs, jellyfish and krill passing in the vicinity.

While the study deployed a small one-meter square turbine, the question now is how researchers might be able to assess the environmental impact of larger, grid-scale turbines. Bassett was therefore careful to avoid describing these results as definitive.

“This information is positive, but is not enough to draw conclusions. More work is needed,” he said, noting how the largest turbines can have a diameter 20 times larger than the one assessed, “but observations to date are generally favorable.” Obermann agreed, highlighting that every site is different and will require tailoring to local ecological conditions.

Despite the need for further study, both expressed cautious optimism about tidal energy’s potential to transform coastal, remote and Indigenous communities. “This collective body of evidence, however messy, should ultimately inform any assessments of risk,” said Bassett, acknowledging similar studies taking place by European researchers with equally positive results.

In Eastport, Maine—the easternmost city in America—plans for tidal power pilot programs are being developed with the goal of one day providing power to this remote corner of the country. If empirical data can continue to overcome the concerns of critics, tidal energy could one day unlock a reliable clean grid across the nation.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,