GLEN ROSE, Texas—After a long journey north through Mexico’s highlands, small songbirds with bright yellow faces descend upon mature canopies of ashe juniper trees in Texas’ Hill Country.

The golden-cheeked warbler nests nowhere else, faithful to the savanna-woodlands of Central Texas, and some, even, to the precise cedar they chose the year before. The birds of passage find a fork among the aged oaks’ branches and weave splintered bark into a cup-shaped nest to raise their young before their annual return south.

The warbler’s buzzy melody heard in and around Dinosaur Valley State Park has become synonymous with the changing of the seasons for bird enthusiasts—the golden song of spring. These tiny migrants, weighing next to nothing, are endangered and have been for more than 30 years as their winter and breeding grounds disappear to development.

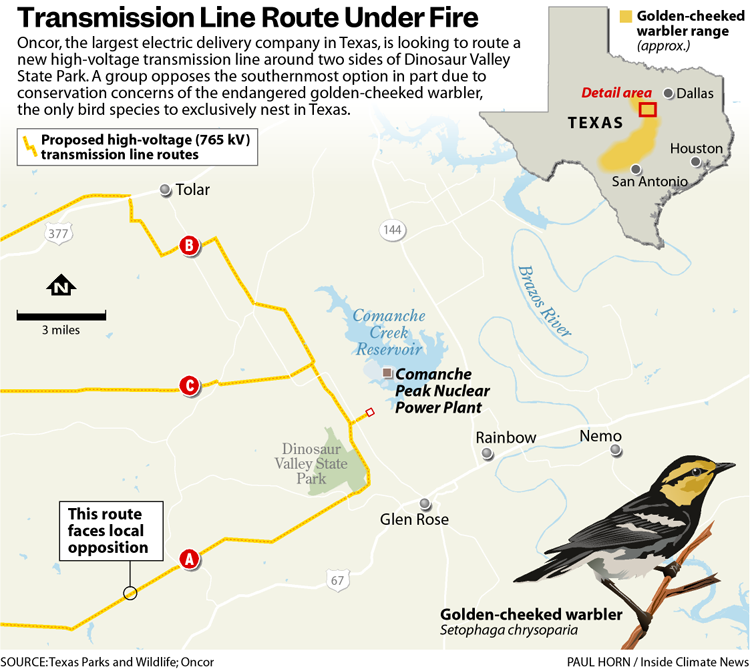

The land here could be next, threatened by a route of proposed high-voltage power lines that would require clearing part of this bird’s habitat and would border part of the state park. It’s but the latest flashpoint in a larger controversy across the state: How will Texas balance its growth while protecting its natural resources?

Or more succinctly: What is Texas willing to give up?

“Imagine you’re a golden-cheeked warbler, and you have flown all the way from Central America to your nesting ground in Texas and it’s not there,” said Rebecca Gibbs, a member of the Dinosaur Valley–Paluxy River Protection Alliance. “It was there last year, and you were there, and you look for it again, and it’s not there.”

Gibbs’ protestations come as the Public Utility Commission of Texas (PUC) is slated to decide whether the state’s largest electric delivery company, Oncor Electric, should construct its new high-voltage transmission line project around the perimeter of the state park, about 75 miles southwest of Dallas, before extending to an existing substation in West Texas, once Oncor files its application next month.

These power lines are just one part of the state’s efforts to expand Texas’ independent power grid and related transmission systems to keep up with escalating demand driven by large-scale data centers, cryptocurrency mines, population growth and the electrification of the oil and gas industry. The PUC and the state’s grid operator, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), are spending billions to fortify the grid and keep large energy-consuming industries in Texas.

“Visitors May Not Return”

Visitors to Glen Rose, home to the preserved dinosaur tracks etched into the limestone bed of the Paluxy River, can see signs of protest against Oncor’s proposed transmission line at nearly every turn. They warn of lost views and threats to wildlife and ecological balance. But the main risk is even closer to home: a threat to the area’s largest economic engine.

“A big chunk of our pie comes from tourism,” said Somervell County Commissioner Jeff Harris. “It’s a huge attraction to this area, the dinosaurs, the fossil rim, the camping opportunities.”

Some 230,000 visitors come to Dinosaur Valley State Park each year. Somervell County estimates that each one of those visitors ends up spending about $12 in the Glen Rose area.

The city leans into the kitschy legislative designation as the “Dinosaur Capital of Texas.” In front of restaurants and along U.S. Route 67 are large plastic figurines of Sauroposeidon and Acrocanthosaurus, the dinosaurs whose fossilized tracks are preserved in the park.

Somervell is the second smallest county in Texas, spanning 192 square miles, and residents soon felt hemmed in when they realized that the routes of the transmission lines would traverse the county and occupy a 200-foot clearing along two sides of the state park.

“We only have so many square feet in this county,” Commissioner Chip Joslin said. “Our resources are even more precious to us.”

The power line installation is part of a plan launched by state lawmakers in 2023 that required regulators to work with grid operators to develop a reliability plan to prepare for the large forecasted energy demands.

The following year ERCOT announced its $33 billion project calling for nearly 2,500 miles of new high-voltage power lines and more than 600 miles of 345-kilovolt lines and other upgrades to existing power lines. A few months later, the PUC approved that plan irrespective of voltage level.

In January 2025, ERCOT filed a comparison of the relative reliability and economic benefits of constructing new 765-kV transmission infrastructure rather than simply expanding the existing 345-kV network to meet future system needs. On April 24, the PUC approved the region’s first 765-kV transmission lines to meet the oil and gas industry’s rapidly growing power needs. It’ll be the highest voltage line in Texas.

These 765-kV lines can each carry up to six times the electrical capacity of the 345-kV lines largely used throughout the state.

While 765-kV lines are being deployed in Texas for the first time, an Oncor spokesperson said, they’ve been used elsewhere across the U.S. and Canada for decades.

Feedback is a critical part of the “environmental assessment and routing study” portion of the transmission project, the spokesperson said. It helps the company refine its preliminary routes before they are submitted to the PUC for further consideration.

“Oncor recognizes the cultural, educational, and ecological importance of Dinosaur Valley State Park,” the spokesperson stated. “All proposed routes are still preliminary, and Oncor must present a geographically diverse set of routes in our application as part of regulatory requirements.”

As leaders try to balance preservation and innovation across the state as they prepare to use eminent domain to cut a path for the massive power lines, Harris said Somervell County’s smallness amplifies the scale. “We don’t have room without it intruding on neighbors—that’s part of the problem.”

Unlike other counties, Harris said, ranches aren’t typically tens of thousands of acres, where the feel of development across a property could be diluted. He said one of the largest properties in his precinct is upwards of 1,500 acres, with most measuring around 300.

“We have been the squeaky wheel on this deal,” Harris said. “We as a county, as a community, have made the noise and made it well known that we do not want that route.

“I’m just hopeful and prayerful that they listen.”

In a presentation shared at a Somervell County Commissioners meeting, a slide detailing why businesses and residents should be concerned read: “Once the landscape is scarred, visitors may not return.”

Those visitors, Gibbs worries, include the small songbird. The 200-foot clear-cut corridor along two sides of the park that’s done for fire safety and maintenance would remove trees and woody vegetation utilized by the warbler.

Matthew Boms, executive director of the Texas Advanced Energy Business Alliance, an industry trade group, said that the regulator’s job of striking the balance between development and preservation is difficult. It’s why he commends PUC commissioners and ERCOT leadership for taking a “forward-thinking” approach.

“It’s really easy to sit on your hands and wait for the growth to happen,” Boms said. “It’s a lot harder and potentially more controversial to actually plan for the growth that’s coming.”

As the state’s population and industries continue to boom, Boms said, Texas doesn’t want to fall behind by continuing to use aging infrastructure.

“We needed the transmission yesterday,” Boms said. “And that was before all the data center load came online.”

Right now, Texas’ transmission system resembles an overcrowded highway, Boms said. The state allows more cars to come on without expanding lanes. The high-voltage transmission system will let Texas have more capacity on the transmission grid and move more electrons around different parts of the state, he said.

Both Somervell County commissioners said they’re not against growth or Texas’ energy businesses. Not too far up the road from downtown Glen Rose, and barely visible from the top of the state park’s overlook trail, is Comanche Peak—a nuclear power plant that provides Texas with roughly 5 percent of its electricity. When it was being built in the 1970s, Harris said, the community was welcoming and saw the positive transformation the nuclear site could have for their little town.

But they don’t see how these power lines will do much other than harm their constituents. The commissioners are concerned about slashed property values and tourism revenue. And they’re concerned about beauty. About the transformation of their residents’ views.

“I have property owners that sit on their front porch and drink coffee every morning and look at a beautiful vista that’ll be staring at these lines,” Harris said.

It’s not that there are no power lines viewable from the state park. Beyond park borders, a line of white poles trails away toward the horizon. There are also power lines on the way to the park.

But none are as big as the 765-kV lines are likely to be. Most standard steel towers for these high-voltage lines are about 15 stories high. The tallest apartment building in Somervell is either two or three stories, the commissioners said.

“We’re not talking about power lines like you see up here,” Harris said at the entrance of the state park. “We’re used to those, and they’re not much taller than the tree line. Now add 150 feet to that, roughly.”

“About to the clouds,” Joslin said.

The proposed routes outlined by Oncor show that the power lines would likely cross the entrance of the park. “It’s going to change the feel just because of the look of them,” Harris said. “You’re not getting out of Dallas and coming to nature where it’s quiet and peaceful and lovely.”

The proposed southern route would traverse the property of Tom and Susan Pardee. In a letter filed to the PUC, the Pardees said the ratepayers and landowners should not have to subsidize the development of data centers.

“These data centers are owned and operated by the most capitalized companies in the world,” Tom Pardee wrote. “These tech companies have access to the capital markets and can fund their own capital investments. The same can be said of the energy industry.”

The PUC has received some 150 protest comments about the proposed routes for the Dinosaur-Longshore line. Included were pleas on behalf of oak trees, filed by fifth-generation Texans, a judge and commissioners from Erath County, and cattle ranchers.

Joslin, the Somervell County commissioner, filed a letter, too, in defense of the “beautiful little County.” He wrote that the proposed lines and their steel towers would “regretfully ruin this for eternity.”

Some of those making comments submitted just photos. They showcase the subtle hills where the transmission lines might go, seemingly asking without words how the state could obstruct this view. And showing, without words, how the open sky there remains a marvel, even in a hilly region of a state infamous for its long, lonely stretches.

“Can’t Say They Didn’t Know”

Gregg Marsh returned to his birthplace of Glen Rose after 34 years away. He was working along the Gulf Coast in Freeport, Texas, at a major chemical company.

In moving back, Marsh became the fourth generation of his family to inherit the large tract now bordering Dinosaur Valley State Park on two sides where Oncor might run one of its power line routes. He also became an unlikely steward of the endangered songbird.

Some five years ago, after he built a home on the land, a Texas Parks & Wildlife biologist recommended he have another biologist come verify that the golden-cheeked warbler nested in the wooded areas of his property, some 2,000 yards from his house.

The recommended biologist played a recording of a male warbler’s song and not five minutes later, Marsh said, a territorial little yellow and black bird flew up. The biologist caught the bird, tagged it with a numbered band and drew blood from its wing for DNA samples.

After proving that the species was on his property, Marsh joined a program involving both the state and federal government that paid him by the acre to improve the birds’ habitat to ensure they came back.

He was told to cut cedar trees with trunks from one to four inches, but not bigger. Marsh cleared the brush to allow the ground to get more sunlight and encourage tree growth. During a survey the next year, the biologist caught the same birds as the year before.

Marsh said he submitted these findings and other research documents to Oncor in protest of the route that would require a 200-foot clearing through his property. “They can’t say they didn’t know,” Marsh said. “They know the warbler is here.”

“We’ll do whatever we can do to keep them here, and we’re gonna try and keep Oncor away from here,” Marsh said.

In the winter months, Marsh can watch cardinals, Carolina chickadees and American Goldfinches by looking out his back window. From there, he hardly ever sees the small bird he and his neighbors are fighting one of the largest companies of its kind over. The enjoyment lies in knowing they’ll be there, even if they’re beyond his line of sight, he said.

There’s pleasure in knowing that come late February, a small fleet of golden-cheeked warblers will arrive on his family’s land. The birds will once again end their annual migration from Central America among the old cedars he’s maintained.

“To know that you’ve improved the habitat to the point where they want to come back,” Marsh said, “that’s the part that makes you feel like you’ve done something for Mother Nature.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,