Researchers say a line has been crossed. For systems like coral reefs and ice sheets, the climate is already past safe.

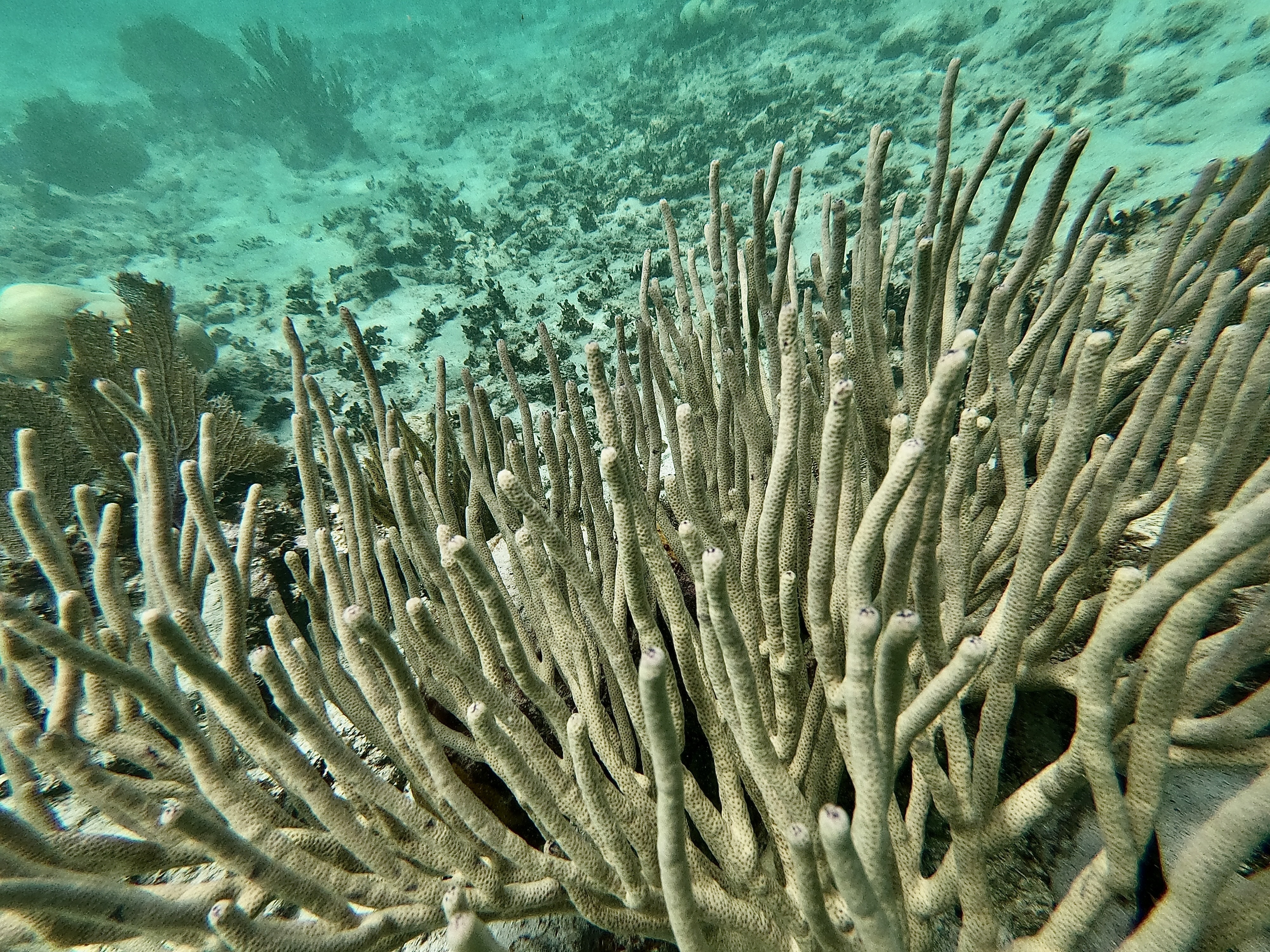

Scientists studying climate tipping points say the world should aim to limit warming to about 1 degree Celsius, warning that the 1.5-degree target enshrined in international climate agreements won’t protect coral reefs, polar ice sheets and other vital Earth systems from irreversible change.

“We have absolute justification to push for a lower number, because one degree is a temperature that is safe,” said Melanie McField, director of the nonprofit Healthy Reefs for Healthy People Initiative.

In the last 12,000 years, the time in which human civilizations developed, the global temperature “very rarely, if ever, crossed plus or minus one degree,” she said Monday during a webinar focusing on governance strategies for achieving global climate targets. For coral reefs, the current warming of 1.2 degrees Celsius is already in the red zone, she added.

The Global Tipping Points Report 2025 was published in October 2025 by a team of more than 160 authors led by researchers at the University of Exeter in England. It synthesizes the latest science on the risks of irreversible change in Earth systems such as coral reefs, ice sheets and forests, as well as the potential to trigger positive tipping points in energy, finance and land use that could quickly reduce climate risks.

The temperature targets refer to human-caused warming since about 1900, when fossil fuel pollution started degrading the climate. The scientists acknowledged that setting a more ambitious climate target could be politically daunting, but recent evidence from studies of ice sheets, reefs and other systems supports their position.

The scientists said the findings show that climate policy needs to be redesigned from an incremental, sector-by-sector approach to one that anticipates tipping-point risks before they unfold. Once critical thresholds are crossed, they said, preventing damage becomes far more difficult and costly than acting earlier to reduce warming and limit overshoot.

”Governance priorities change fundamentally,” said Simon Willcock, an environmental geography professor at Bangor University in Wales. Instead of trying to avert system collapse, governments must then focus on limiting the damage.

He said governments need to be able to quickly detect system shocks and coordinate emergency responses for impacts rippling across borders and sectors. Even after tipping points are crossed, governance can keep disruptions manageable and help prevent them from spiraling into wider socioeconomic crises.

In an era of geopolitical fragmentation, “the question is no longer whether cooperation is difficult, but whether we can afford not to cooperate,” Willcock said. “The choices made in the next decade will determine not only which tipping points are avoided, but also which futures remain possible.”

The scientists also noted recent research that looked at the economic part of the equation, and highlighted the global financial system as both a source of systemic climate risk and a potential driver of rapid change.

The financial system faces climate risks from tipping points that threaten trillions of dollars in assets, from coastal infrastructure to agricultural supply chains, yet many institutions have not accounted for tipping-point risk in their models. The Global Tipping Points 2025 report argues that incorporating those risks into stress tests and redirecting investments toward decarbonization and sustainable supply chains could help trigger positive tipping points that reduce the likelihood of catastrophic outcomes.

Overall, the financial sector remains largely unprepared for the speed of tipping-point impacts, which can crash asset values rather than unfold gradually, as most climate risk models assume. But tipping points can trigger sudden losses, creating a domino effect across markets, governments and insurance systems.

Finance could play a decisive role in preventing the worst outcomes if capital is steered more deliberately. Shifting investments toward clean energy, climate-resilient infrastructure and sustainable supply chains, and lowering the cost of capital in lower-income countries, could help accelerate improvements to energy, food and land-use systems that would reduce the overall risk to the global economy.

The report emphasizes there is potential for relatively small coalitions of actors to tip the wider system toward more sustainable climate policies, said Tom Powell, a University of Exeter scientist who studies positive tipping points.

If there is coordination by a few key actors in supply chains, from producers to major markets, “it can have tremendous power to tip that system from an unsustainable state into a more sustainable one,” he said. If most major markets adopted deforestation-free soy production, he added, it could become the norm.

“The time where we should anticipate global cooperation and everyone pulling in the same direction is over,” added Willcock. “If you have a few key countries doing the right things in key areas, that can be enough to tip the whole world into a positive tipping point state.”

He noted the human rights context of climate tipping points because vulnerable populations, Indigenous communities, low-income regions and future generations suffer the brunt of the impacts, even though they did little to cause the crisis.

Systems most at risk, including coral reefs, tropical forests and low-lying coastlines, directly support livelihoods, food security and cultural identity in regions with limited political and financial power in the Global South. But those communities often have the least influence over global emissions and climate policy.

The researchers participating in the webinar argued that governance responses must explicitly address inequity by thinking about who participates in decision-making and who bears the costs of climate damage. Without that focus, they warned, tipping points could amplify existing social and economic inequalities alongside environmental loss.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowFraming tipping points as human rights issues is already reshaping how some governments and legal scholars think about climate governance, including growing efforts to recognize the rights of nature in national laws and international forums. Such approaches, the scientists said, reflect a shift toward protecting ecosystems not only for their economic value today, but for the people and generations who will inherit the consequences of decisions made in the coming decade.

Avoiding catastrophic climate change is not only about lowering the global thermostat. It will require governments to actively trigger positive tipping points that create economic opportunities for rapid decarbonization.

Sectors like solar and wind energy and electric vehicles, have already passed tipping points in key markets, proving that rapid change is possible, Willcock said, adding that the same dynamic can apply to nature restoration and food systems, including deforestation-free supply chains.

“The goal,” he added, “is to create conditions where a sustainable technology or behavior is the most affordable, attractive and accessible option, so it becomes the obvious thing to do.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,