After years of relying on voluntary grant and incentive programs to bring down a potent climate pollutant from dairy and livestock operations, California is looking into developing a rule to require reductions directly.

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) put out a request for feedback last week as it seeks to meet the requirements of Senate Bill 1383, a 2016 law that obligates the state to reduce its methane emissions 40 percent from 2013 levels by 2030.

Rules for regulating methane from organic waste and landfills under the law went into effect years ago, but dairy and livestock businesses were exempted until 2024.

Environmental advocates say they’re hoping CARB’s call for information on the best ways to track and reduce dairy methane as it looks to implement the state law will prompt new approaches for addressing livestock industry pollution.

“It can lead us to a better solution for the state’s manure problem,” said Phoebe Seaton, co-director of the Leadership Council for Justice and Accountability, an environmental justice group that works with rural communities in inland California. “We’ve been asking for many, many years for an honest and intensive assessment that will identify what an effective and fair regulatory framework is.”

Comments are due by March 30. After that, it’s uncertain if and when the state will embark on a rulemaking process. The request only asks a series of questions about how the state might best track methane emissions from dairy and livestock, what types of reporting requirements it should implement and what mitigation strategies it should prioritize, especially given the law’s requirement that regulations be “technologically and economically feasible.”

“It seems like they at least want to better understand what the current state of the emission inventory is and what some potential leverage points might be to reduce those,” said Kevin Fingerman, a professor who studies bioenergy at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt. “They are trying to think creatively about how to bring down emissions without scaring animal agriculture out of the state entirely.”

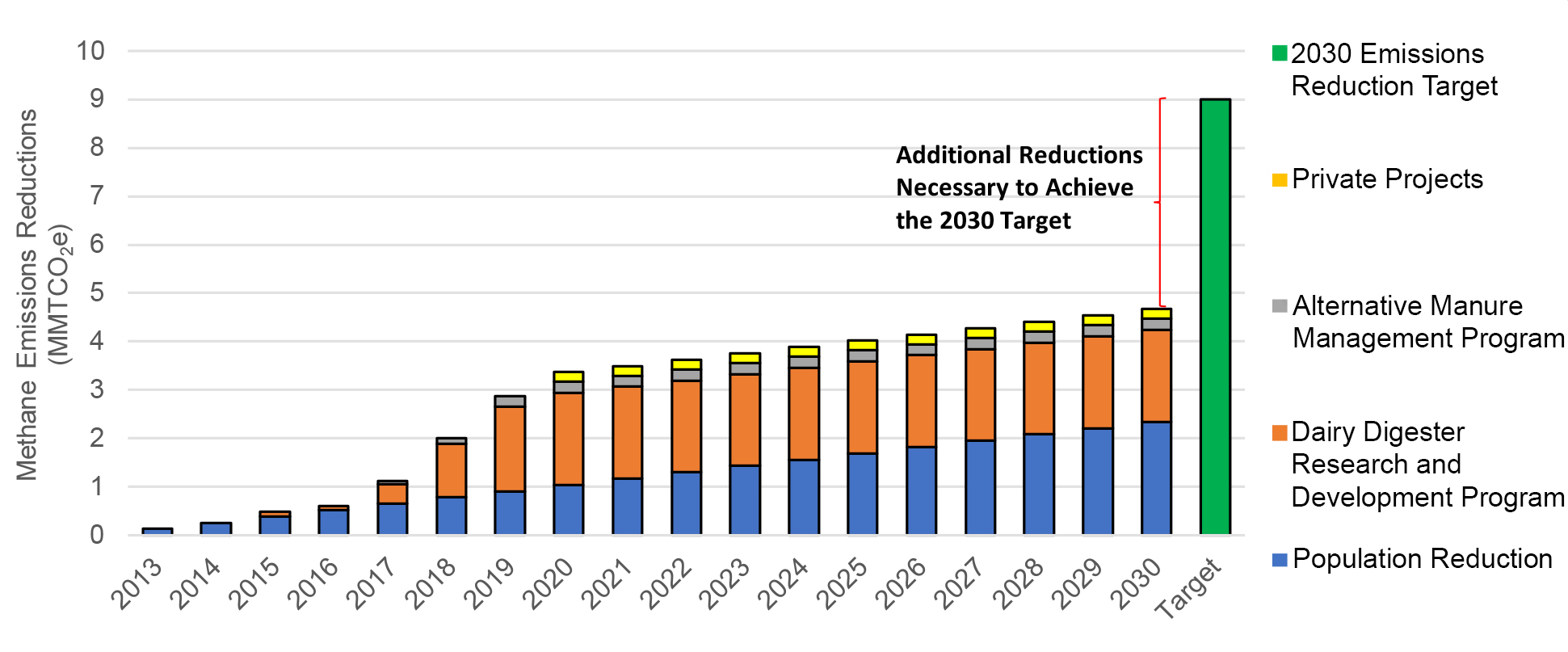

The dairy and livestock sectors produce more than half of California’s methane emissions and most of those come from dairy cow burps and manure. According to a 2022 CARB report, current programs, coupled with statewide declines in animal populations, have California dairy and livestock operations on track to reach annual reductions of as much as 5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent by 2030. That’s a little over half of the 9 million metric tons in annual reductions the sector would need to make to reach the 40 percent goal by then.

The vast majority of current and projected dairy emission reductions driven by state programs come through California’s initiatives to fund anaerobic digesters—tarp-like devices that farmers install over their manure lagoons to capture methane gas, which they then burn to generate electricity or convert into renewable natural gas.

The state supports these systems through the California Department of Food and Agriculture’s Dairy Digester Research and Development Program, whose grants are funded through the state’s cap-and-invest program, and CARB’s low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS), which credits farmers for the fuel they produce from digesters.

But the latter of these programs has been highly controversial with scientists and environmental justice groups, who say it creates a perverse incentive for California dairies to expand their herds to produce more fuel, thus increasing the local pollutants—like nitrogen, phosphorous and ammonia—that come from dairy manure but aren’t addressed by digesters. The agency, for its part, has disputed that digesters are a factor accelerating herd growth.

Environmental groups also say the LCFS is drastically over-crediting dairy biogas, and diverting needed resources from more efficient and cleaner fuels.

The program sets an average carbon-intensity threshold for transportation fuels in the state and requires producers that exceed the limit to buy credits from others that fall below it. Fuels generate more credits for having lower carbon-intensity scores. But dairy biomethane fuel, which emits greenhouse gases when combusted, receives a negative carbon intensity score, while fuels that are actually carbon-free, like electricity generated from solar power, might only receive a score of zero. That’s because the program takes the emissions from dairy manure on farms as unavoidable and credits digesters that capture it as though they were “removing” that methane from the atmosphere.

While dairy biogas makes up about 1 percent of the fuel volume supported by the program, it’s the most lucrative fuel to produce, generating about a fifth of the credits.

Last November, when CARB was updating its LCFS program, environmentalists pushed to reduce the dairy biogas credits, but regulators decided to keep offering them at the same level until 2040, and until 2060 for projects that break ground before 2030. At the same time, the board passed a resolution initiated by Diane Takvorian, the board member appointed to represent environmental justice groups, requiring CARB to “prepare a plan for initiating, developing, proposing, and implementing a livestock methane regulation.”

Advocates had hoped that the separate regulation would bring down credit values for dairy biogas in the same way that regulations do for methane gas from landfills. The latter fuel receives fewer credits under the LCFS than dairy biogas because landfill methane is already regulated in California, and the program doesn’t allow CARB to count legally required emission reductions in its carbon intensity calculations for fuels.

But staff made a last-minute change before November’s LCFS vote to allow the 30 years of high-value credits for dairy biogas projects initiated before 2030 regardless of what happens with a new rule.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“It is a bit of a poison pill but it doesn’t undo the fact that they are directed to move forward with a rule,” said Takvorian in an interview two days after the vote. “The strong feeling on the part of the board members was that livestock [methane] needs to be regulated, and we need to develop rules to do that, and we need to develop a timeline that we will stick to.”

The resolution directed staff to start the rule development process in 2025, with a board vote by 2028 and a rule in effect by 2030. The staff missed the initial deadline, and kicked off the process with the request for feedback last week.

CARB spokesperson Lindsay Buckley said in an email that the staff is “aiming to follow board direction on the timeline” for the rule.

According to SB 1383, the 2016 bill requiring statewide reductions of methane emissions, the state can only implement dairy and livestock regulations on or after 2024 if it finds the rules are technologically and economically feasible, as well as cost effective, and that markets exist for products like biogas and composting generated from manure management. Rules have to include provisions to prevent dairies from simply moving out of the state and continuing to emit elsewhere.

CARB’s 2022 analysis found that while the state has made progress in developing a biogas market, procuring biomethane can cost six to 10 times more than fossil gas, and persistent barriers to installing digesters remain. The state has made even less headway addressing the methane released in cow burps and gas, created by a biological process called enteric fermentation, and in promoting alternative manure management, practices often preferred by environmentalists and environmental justice advocates that lower emissions of methane and other pollutants without the use of a digester.

On the cow burp front, two feed additives are commercially available that can reduce emissions up to 10 or 20 percent, and others are under development, the report said.

Examples of alternative manure management practices include separating solid from liquid manure and pasture-based management. These reduce methane emissions by managing manure in drier conditions and avoiding or limiting the oxygen-free conditions found in wet manure management systems typically used by large concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, which use water to flush manure from barns into lagoons. That creates the ideal oxygen-free, or anaerobic, conditions for methane-producing microorganisms.

Digesters capture methane from anaerobic systems, but environmental groups point to leaks and emissions from digester waste. They say the alternative methods, which store manure in its solid form or let it dry in the sun, reduce the formation of methane while avoiding the incentive to grow herds.

“What’s extremely important to us is that the rule also addresses the concomitant water and air pollution,” said Seaton, of the methane rule CARB is planning. “Digesters are not addressing the full scope of pollution and impacts.”

California has an incentive program to support alternative manure management practices, but most of the factory farms in the state use wet manure systems that allow them to manage large quantities of livestock waste at lower costs. And the state has spent less to encourage alternative practices. The state’s grant program for alternative manure management has awarded $127 million, while its grant program for digesters has given out $228.7 million, and that’s separate from the LCFS, which provides hundreds of millions each year for digesters.

CARB’s 2022 report said making half of the remaining reductions the state needs to reach its 2030 target with digesters and half with alternative manure management projects could cost between $800 million and $3.7 billion. Using only digesters could cost between $700 million and $3.9 billion.

Michael Boccadoro, head of the California trade group Dairy Cares, said he hopes to see an expansion of the existing incentive programs across the board to get the dairy sector to 40 percent reductions.

“We appreciate CARB seeking the facts about the tremendous progress being made by the state’s dairy farm families and how existing incentive programs can be expanded and enhanced as we make the final push toward 2030,” he said in a text.

Tyler Lobdell, senior attorney with the advocacy group Food and Water Watch, is hoping for more change in the way the state spends its money to get dairies to meet the 2030 methane reduction goal.

“The state has spent untold millions and given mega-dairies every possible advantage to push expensive, ineffective factory farm biogas projects that have done the opposite by encouraging factory farms to get bigger and pollute more,” he said in a statement. “CARB is finally starting the process to implement SB 1383 regulations, which will be a critical opportunity to get California’s climate efforts back on track.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,