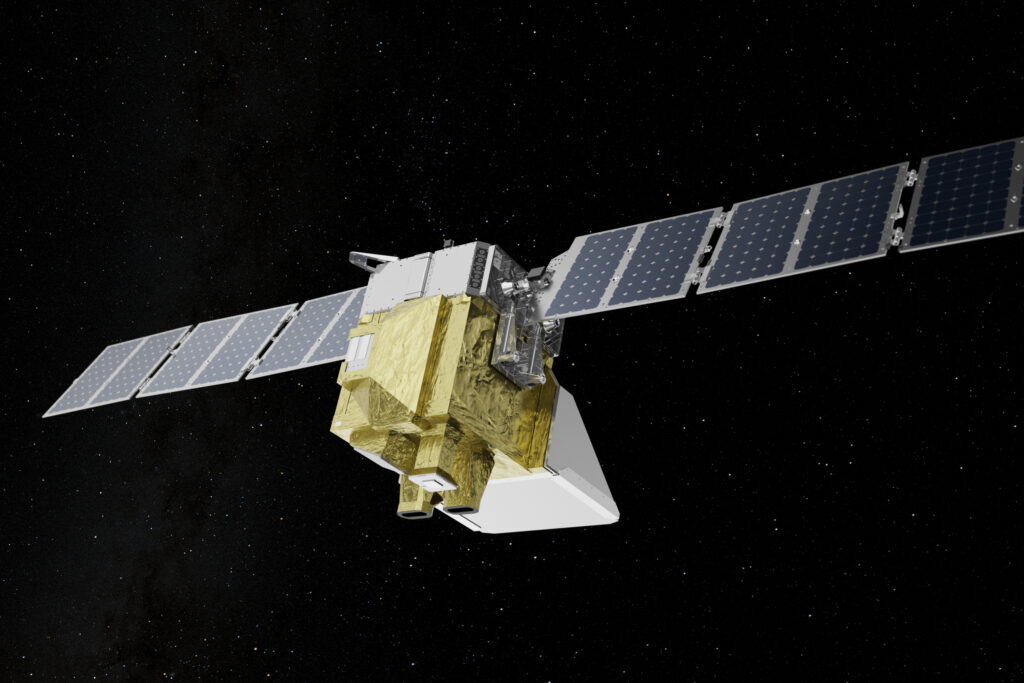

MethaneSAT, the world’s most advanced methane-detecting satellite and first spacecraft owned by an environmental nonprofit, promised to usher in a new era of climate accountability when the device entered Earth’s orbit in 2024.

One year later, researchers with the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) lost contact with the $88 million satellite, but not before downloading a trove of data collected over the prior year. Now, an initial assessment of data shows that methane emissions from oil and gas basins worldwide far exceed what is reported in official emissions inventories and fall short of targets set by major companies.

The early look at MethaneSAT’s system-wide analysis, published on Feb. 2, includes 45 oil and gas producing regions, which account for half of the world’s onshore oil and gas production. Measurements were collected for just over a year, from May 2024 to June 2025.

Steven Hamburg, chief scientist at EDF and MethaneSAT project lead, said the data will be crucial for shaping regulations and improving methane mitigation strategies in the oil and gas industry.

“We really need that kind of dynamic, empirical data to really make the situation clear and reward those who are doing well and call out those who are not,” said Hamburg, who works on MethaneSAT along with researchers from Harvard and other partners.

Emissions of methane, the leading driver of climate change after carbon dioxide, were 50 percent higher on average than official estimates, including the U.S. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory. The Permian Basin of West Texas and southeast New Mexico, the world’s largest oil-producing region, had the highest total methane emissions, releasing an estimated 410 metric tons per hour. The data have not yet been peer reviewed.

The rate of methane released varied widely, from 0.6 percent of all marketed gas production in the Appalachian Basin in the eastern U.S. to more than 20 percent of all gas brought to market in the Widyan Basin in Iraq. Emission rates varied between basins where oil is the primary product and those where more gas is produced. Even basins with the lowest methane-emissions intensity released the pollutant at a rate several times higher than oil and gas industry goals.

The Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter, a voluntary agreement by 56 of the world’s leading publicly traded and national oil and gas companies, including ExxonMobil, Shell and Aramco, pledged to reduce their collective methane emissions intensity to 0.2 percent by 2030.

“The U.S. oil and natural gas industry is working every day to meet rising energy demand while reducing methane emissions,” said a spokesperson for the American Petroleum Institute. “We will continue working with the Trump administration on a balanced approach that lowers emissions while supporting American energy leadership.”

The Trump administration has delayed and repealed regulations adopted during the Biden administration to limit methane emissions in the oil and gas sector.

“Confirms What We’ve Known”

EDF’s Hamburg said MethaneSAT provides a global view of emissions, unlike flyover data collected from aircraft or measurements taken by personnel on the ground.

“Satellites are absolutely essential to doing these kinds of comprehensive, grounded, high-quality data products,” he said.

Hamburg said the ability to make an “apples to apples” comparison between oil and gas basins around the globe is “exactly what we need” to understand emissions and drive mitigation.

Rob Jackson, a professor of earth science at Stanford University who was not involved in the current assessment, cautioned that the findings haven’t been confirmed through a peer-reviewed study published in an academic journal, but said they align with prior research.

This “confirms what we’ve known for more than a decade, which is that we substantially underestimate methane emissions from oil and gas production,” Jackson said.

The report found that 40 percent of methane emissions, which can include gas leaks as well as intentional venting, in eight regions across the U.S. came from areas that are responsible for less than 7 percent of gas production.

“Wells that are low producers tend to be old, they tend to be less efficient and they tend to be leakier,” Jackson said. “You’re getting more methane emissions for less oil and gas. We need incentives to shut some of those low-producing wells down.”

Jackson noted that the emission intensities in the report were based on gas brought to market rather than total gas produced. Regions like the Permian Basin, which prioritize oil production over gas, often flare excess gas that may not be captured in the MethaneSAT report.

The report notes that methane intensity can also be calculated by comparing emissions to the total energy produced from both oil and gas. Hamburg said they will release additional comparisons to address differences between basins that primarily produce oil and those that focus more on gas.

Jackson also noted that the report provided only a single figure for each basin’s emissions intensity, rather than a range of values and the relative uncertainty of those figures, as is typically done in a peer-reviewed study. The team’s loss of contact with the satellite also means MethaneSAT won’t be able to show how climate pollution from a particular oil and gas region changes over time, Jackson said.

Hamburg said that future peer-reviewed papers would include emissions intensity ranges, but that this report focused on making initial data public as soon as possible. He said the MethaneSAT team would continue to analyze and publish data they collected from before they lost contact with the satellite, which lost power and was deemed unrecoverable.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowOne country not included in the current assessment is Qatar, home to the world’s largest natural gas field and a leading exporter of liquefied natural gas after the United States. The country’s gas deposits are primarily offshore, making satellite-based methane monitoring, which typically relies on bouncing light off the ground, more challenging.

Hamburg said MethaneSAT researchers were beginning a more nuanced data collection process in offshore gas-producing regions when they lost contact with the spacecraft. The ability to quantify and compare methane emissions associated with natural gas across countries, particularly those that export LNG, will become increasingly important in the coming years. The European Union and Japan, the world’s leading LNG importers, are currently implementing regulations on energy imports that could impose fees on LNG with higher associated methane emissions.

Robert Howarth, a professor of ecology and environmental biology at Cornell University who is not part of MethaneSAT, questioned whether gas from any of the basins in the current analysis would qualify as having a low-methane intensity.

Regulatory Backstop, Persistent Emissions

MethaneSAT’s initial report attributes a “powerful benefit” to state-level methane regulations. Data released in 2025 by MethaneSAT showed that methane intensity on the New Mexico side of the Delaware Basin, a sub-basin of the Permian Basin, was less than half that observed on the Texas side. The satellite observed methane intensity of around 1.2 percent in New Mexico and around 3.1 percent in Texas. While MethaneSAT data indicate New Mexico has lower methane intensity, production has increased significantly in both Texas and New Mexico in recent years.

New Mexico adopted methane regulations in 2021 that require operators to minimize venting and flaring, conduct regular leak detection and use cleaner equipment. The rules require oil and gas operators to capture 98 percent of their natural gas by the end of 2026.

Texas has no such regulations and state regulators opposed the methane regulations introduced by the Biden administration, which the Trump EPA has since rolled back.

The Permian Basin had the largest disparity between satellite-detected emissions and EPA-reported emissions. MethaneSAT detected an emissions rate four times higher than reported in the inventory.

One contributor to overall oilfield methane emissions is natural gas flaring, a common method for disposing of excess gas at wells. While designed to burn methane, flares are not 100 percent efficient and release some amount of methane to the atmosphere.

Texas agencies that regulate the oil and gas industry prohibit flaring in most cases, but previous reporting by Inside Climate News and ProPublica found that companies can readily obtain exemptions from the prohibition to flare or vent large quantities of gas.

Charlie Barrett, a thermographer documenting oilfield emissions and pollution for the nonprofit organization Oilfield Witness, said he has not seen progress in New Mexico’s Permian Basin. He said flares are still commonplace.

He said the cumulative emissions from thousands of abandoned and operational wells in disrepair are significant. “These are small conventional wells, but they are emitting 24/7, 365 days a year,” he said. “They have been emitting for at least the four and a half years I’ve been going out there.”

Barrett said that as oil and gas production increases in New Mexico, emissions will continue to rise.

“How can you mitigate something when you continue to expand the industry?” he said. “The pace of climate change far outpaces our regulatory framework.”

Hamburg said additional satellites, including those launched by the space agencies of Japan and the European Union, will continue to improve the global monitoring network for methane and other climate pollutants. Hamburg didn’t rule out the possibility that EDF may launch a satellite of its own again in the future.

“We’ll be public when we know what we are doing going forward,” he said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,