More than half a century ago, at Queen’s University Belfast in Northern Ireland, Michael McElroy’s classmates had just finished an exceptionally difficult math exam and were ready to vent. But first they wanted to hear from the class’s star student.

“So Michael comes rushing up, and they said, ‘What did you think?’” Veronica McElroy, Michael’s wife of 64 years, recalled.

When Michael said the test was “horrendous” and that he was barely able to finish, the other students were relieved, Mrs. McElroy recalled.

“If McElroy found it hard, they were free and clear,” or so they thought, she said.

But her future husband had misunderstood the professor’s instructions. Students were supposed to complete three problems on the test. Michael, she said, finished all 10.

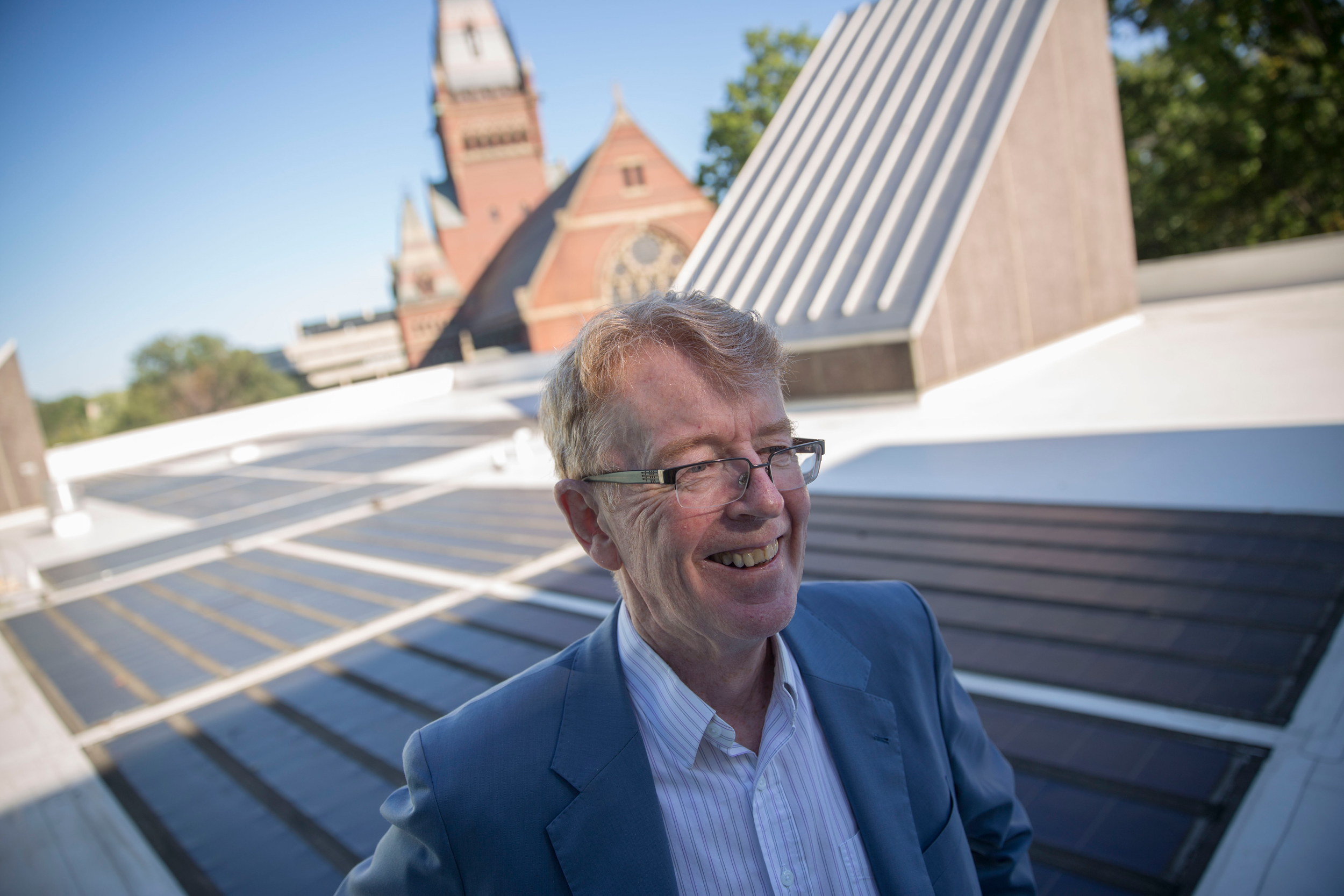

Michael McElroy, who went on to become a pioneering atmospheric scientist, died of cancer last month at 86. He was the Gilbert Butler Professor of Environmental Studies at Harvard University and chair of the Harvard-China Project on Energy, Economy and Environment.

McElroy was “a titan in the scientific world who was generous in his interactions with people around the world,” said Chris Nielsen, executive director of the Harvard-China Project. His academic pursuits were broad and evolving, from early planetary research at the height of the space race to later work on climate and environmental challenges.

“He was a guiding light to many young and not-so-young scientists because of his in-depth understanding of atmospheric chemistry and its wider implications,” said James Hansen, former director of the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies, and one of the world’s leading climate scientists.

McElroy was born in County Cavan, Ireland, on May 18, 1939, and grew up in Belfast. The son of a banker, he earned a Ph.D. in applied mathematics from Queen’s University in 1962. He then worked as a physicist at Kitt Peak National Observatory near Tucson, Arizona, where he developed a general theory to describe the upper atmospheres of Earth and other planets.

Hansen recalled marveling at a lecture that McElroy delivered at the observatory on the atmosphere of Mars.

“McElroy was Kitt Peak’s golden boy,” Hansen recalled.

His atmospheric research earned McElroy the 1968 James B. Macelwane Medal from the American Geophysical Union, the organization’s highest honor for early career researchers in Earth and space science.

At age 31, McElroy joined Harvard in 1970 as one of the youngest tenured faculty. While there, he worked as a scientist on NASA’s Viking Project, the first spacecraft to land on Mars.

At Harvard, McElroy increasingly focused on Earth’s atmosphere, including the threat that man-made chemicals posed to atmospheric ozone, which protects Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. In a 1971 report for the National Academy of Sciences, he urged the space agency to send a spacecraft to Venus. At a time when few considered climate change, the report noted that Venus’ atmosphere could shed light on whether rising man-made increases in carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere could lead to higher temperatures, “resulting in the runaway greenhouse effect.”

“He was very curious about things that people were doing that would have a global impact,” said Steve Wofsy, an atmospheric and environmental science professor at Harvard and one of McElroy’s first postdoctoral students. While such thinking is commonplace today, it was not the case in the early 1970s, Wofsy said.

Wofsy said it was McElroy’s interest in uncovering how things work that drew him in. “For a person like myself coming into a new field, it was like, ‘Wow, this is where I want to be,’” Wofsy said. “It was just really exciting to be around him.”

McElroy and Wofsy were part of a team that demonstrated how bromine and nitrous oxide contributed to ozone depletion, explaining how the ozone hole over Antarctica formed so quickly.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe research helped shape the Montreal Protocol, a landmark environmental treaty that phased out production of ozone-depleting chemicals worldwide. Their findings also led to McElroy’s collaboration with a young U.S. senator from Tennessee and future vice president, Al Gore.

“He immediately impressed me with his deep expertise on the issue as well as his unusual ability to communicate clearly to a lay person like me—not only about the science but also about the urgent need for policy action,” Gore wrote in a statement. “Mike McElroy was a brilliant, path-breaking scientist, a true leader in the scientific community, a highly valued colleague, and a dear friend.”

In 1995, McElroy served as the chairman of Measurements of Earth Data for Environmental Analysis, a task force formed by Gore to use U.S. intelligence data for environmental research, including information about security challenges linked to climate change.

“His work to develop and deepen ties between scientists, economists, policymakers, and academia on the greatest challenge of our lifetimes – the climate crisis – will continue to pay dividends for decades to come,” Gore said.

In addition to his wife, McElroy is survived by their children, Brenda “Bren” McElroy and Stephen McElroy, and two grandchildren.

Unafraid to challenge conventional wisdom, McElroy could be contentious.

“He felt strongly about things, and he didn’t defer,” Nielsen said. “But that’s also part of being a good academic, being hard-headed in what you think and debating things with people.”

Over the decades, he launched key environmental initiatives at Harvard, led the university-wide Committee on the Environment, helped found the Environmental Science and Public Policy concentration, and founded the Harvard-China Project on Energy, Economy and Environment.

In 2024, McElroy was awarded the American Geophysical Union’s highest honor, the William Bowie Medal, for his significant contributions to the field of Earth and space science.

“I am proud of the research, teaching, and the opportunity I’ve had to shape young minds,” McElroy said at the time. “What also stands out are the collaborations I’ve had with colleagues across Harvard, China, and the world, and the enduring connections and friendships I’ve built.”

McElroy retired from teaching on Dec. 31 but planned to continue his work with the Harvard-China Project. Since its inception in 1993, the program has brought hundreds of students, postdoctoral fellows and visiting scholars to Harvard to collaborate with students and researchers in climate and environmental sciences and other disciplines.

Nielsen and McElroy often engaged with senior Chinese government officials, including Xie Zhenhua, China’s former climate envoy and a key architect of the Paris Climate Agreement.

“Mike was a dear friend of mine for many years,” Xie wrote in a statement to Inside Climate News. “His academic achievements, dedication, and dignified demeanor were truly admirable.”

Quoting a Chinese idiom from Han dynasty historian Sima Qian, Xie described McElroy as someone who didn’t engage in self-promotion, but nonetheless attracted others.

“The peach and plum trees do not speak, yet a path is formed beneath them,” Xie said. “Mike nurtured many talented individuals who have contributed significantly to environmental protection, climate change mitigation, and sustainable development. He will be deeply missed.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,