Nearly every Monday morning, five restorationists with Conserving Carolina guide volunteers through the steep hills of Norman Wilder Forest in Tryon, North Carolina. Armed with chainsaws, thick gloves and a pickaxe-like mattock, the group goes hunting for a wily prey: kudzu.

The forest’s most prominent features have been overtaken by the invasive vine. The “Kudzu Warriors” cut down what they find and pull up root crowns to try to prevent regrowth.

Reclaiming the landscape is only one of the kudzu volunteers’ motives. There’s an urgency to this work for another reason: the plant’s extreme wildfire risk.

When kudzu vines tangle themselves onto the crowns of trees and dry out in the winter, they can become a dangerous “ladder fuel,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. One spark near the ground can easily ignite the vines, the flames climbing to the tops of trees.

That’s already happened in Tryon. When high winds downed a power line in March 2025, a spark on a patch of kudzu unleashed a 600-acre forest fire, according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

In a separate incident that month, Kudzu Warrior volunteer Don Dicey was on the ground when fires broke out in Pacolet, South Carolina, a small town about 20 miles from the North Carolina border. He said visiting fire crews from Indiana told him that whenever flames touched a vine, “it went up like somebody just poured gasoline on it. That’s how combustible they are, how dry.”

Crown fires are much hotter, faster and harder for firefighters to control than ones contained to the forest floor.

“When you’re thinking about increased fire risk, the amount of fuel, the structure of the fuel, the connectivity of the fuel and the moisture of the fuel matters,” said Chelsea Nagy, deputy director of the University of Colorado Boulder’s Earth Lab. “If you have a lot of fuel that’s present, and it’s all connected and it gets dry and then there’s a fire, that leads to trouble.”

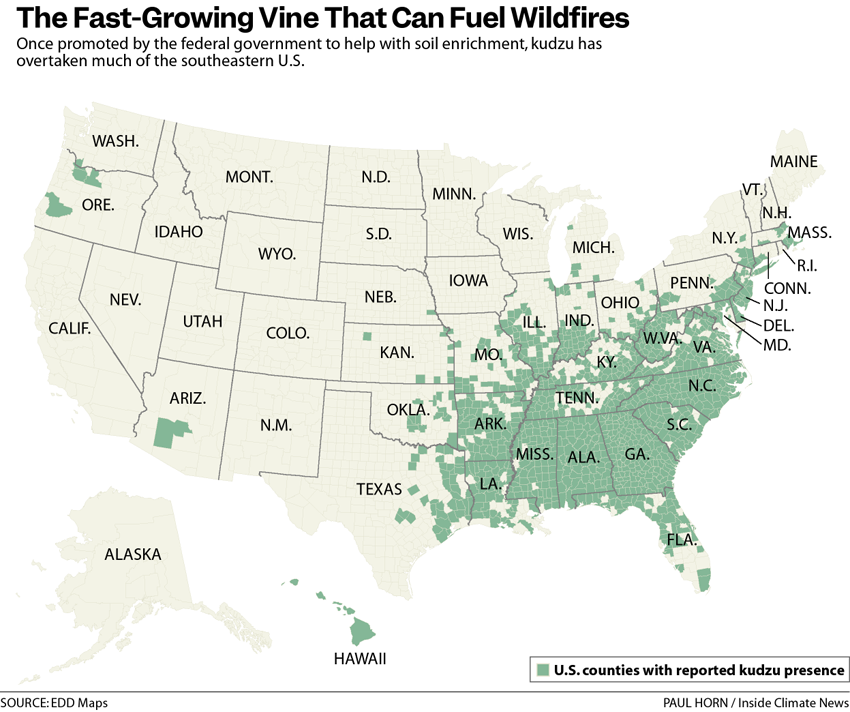

Kudzu is most widespread in the South, but it has reached 32 states, increasing wildfire risk from Florida to Washington state and Massachusetts. It wouldn’t have happened if not for a decades-old experiment in land management.

How Kudzu Overran the South

As a result of relentless monoculture farming, Southern soil was stripped of its nitrogen, leaving little of the nutrient for native grasses and crops to grow. By the 1930s, the U.S. government was frantically searching for soil-enrichment solutions.

Kudzu, a Japanese plant first introduced as a decorative vine for porches during Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition in 1876, looked like a winner.

The federal government began paying farmers $8 an acre to plant kudzu seeds in farmland across the South. Channing Cope, then farm editor at the Atlanta Constitution, was instrumental in advocating for kudzu’s usefulness. Through both his acclaimed newspaper column and radio show, Cope claimed that kudzu was a “miracle vine” and that only its “healing touch” would bring the South out of its agricultural troubles.

At first, the kudzu did revitalize the soil, allowing crops to flourish. But the invasive vine soon grew out of control: spreading nearly a foot a day, rooting wherever it touched and earning the nickname of “the vine that ate the South.” Agriculturalists and engineers called it unmanageable as it engulfed forests and destroyed telephone lines. David Coyle, associate professor of forest health and invasive species at Clemson University, said these habits are common signs when distinguishing between invasive and native species.

“Invasive plants have a few characteristics that native ones don’t. One is a super-high growth rate and a super-high reproductive rate. Every time one of those section junctions hits the ground, it just starts roots. There are really no natural enemies,” said Coyle.

The U.S. government, realizing that its solution created a problem, stopped paying farmers to plant kudzu in 1953. The USDA officially classified it as a weed nearly two decades later.

The federal government has no current-day estimates on the number of acres that kudzu covers in North Carolina, but the vine is all over the place, causing trouble.

“You can get a reduction in forested area just by virtue of the vine moving in,” said Sara Kuebbing, research director of Yale University’s Applied Science Synthesis Program. “It can also change how carbon or water cycles move through that soil.”

In Norman Wilder Forest, “you literally can stand there and for 180 [degrees], just by turning your neck, see nothing but kudzu that has taken over all the trees and covered them and killed them all because it can smother them,” said Ford Smith, a Kudzu Warrior and board member at Conserving Carolina.

Combating Kudzu at Home

Some in North Carolina are following in the footsteps of the Kudzu Warriors and tackling the invasive plant head-on. In 2013, the city of Tryon and the Pacolet Area Conservancy “hired” a herd of 25 goats to clear out kudzu in the downtown district.

David Lee, natural resources director at Conserving Carolina, said the difficulty of the effort depends on the scale of the problem.

“If the infestation is small, just getting started, I’d get a shovel and start digging out the roots. For larger infestations, climbing trees and covering multiple acres, you have to start thinking differently,” Lee said. “Kudzu doesn’t respect property boundaries, so collaboration with neighbors is key.”

Coyle added that while such efforts will help with small batches, removing kudzu from entire regions—and reducing the fire risk it represents—will be nearly impossible.

“We’re never going to be rid of kudzu on a regional scale. You’ve got to pick your battles. It’s a multi-year commitment,” he said. “You kill that top layer of kudzu, there’s a seed bank under there that’s going to grow up again the next year. It just takes a commitment, and it’s hard.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,