TURKEY, N.C.—The Align RNG biogas processing facility here is so small, you would miss it if you weren’t looking for it. Just four small silver mounds beside a massive 100-foot grain silo under which trucks drive day-in, day-out loading up with hog feed.

In a landscape dominated by the infrastructure of hog and poultry farming—slaughterhouses, barns, slat manufacturers and truck washers—the mounds could be mistaken for backup generators or small storage tanks from a distance. But they’re actually part of a boom in turning hog waste into renewable natural gas (RNG) that’s building out hundreds of miles of underground pipelines, catching locals off guard and raising concerns across eastern North Carolina about the technology’s potential to increase pollution that isn’t carried away in the pipes.

Adding even more complexity to the biogas controversy in the region is the fact that a California-funded project sits at its heart.

“We’re asking people in the community, ‘What’s in your backyard?’” said Devon Hall, an environmental justice organizer who founded the Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help (REACH) in Warsaw, North Carolina, about fifteen minutes down the road from the facility. “Some of this is happening under the radar.”

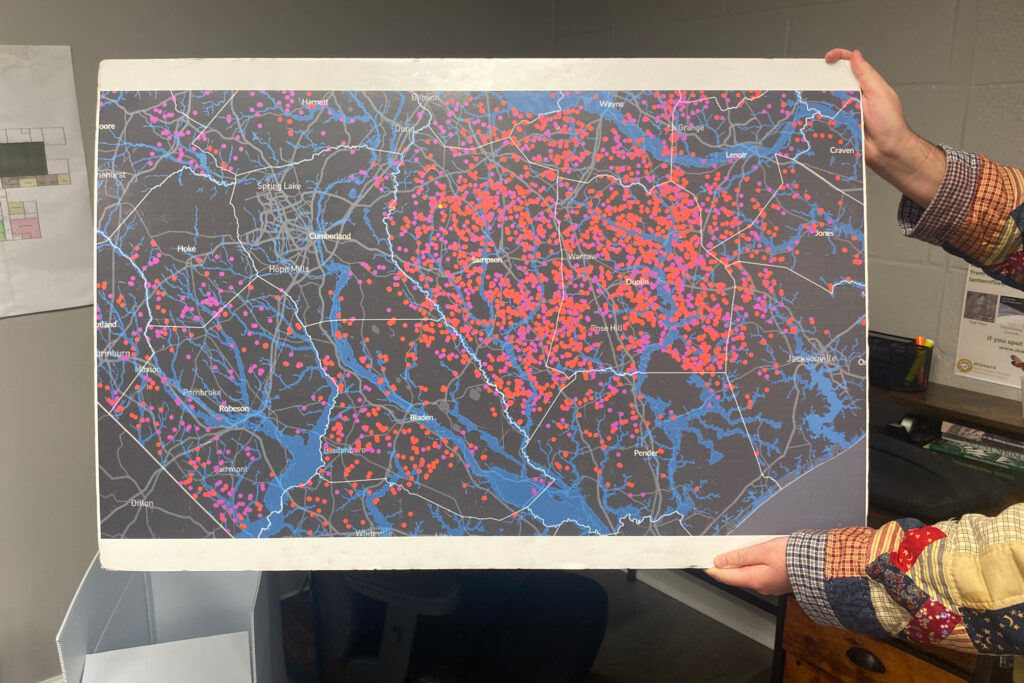

REACH is based in Duplin County, the second-most hog-dense county in the U.S. after neighboring Sampson County, where the Align RNG plant is located. Pigs outnumber people in the region about 40 to 1, but you can’t see the hundreds of combined animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, where pigs live crammed tightly into pens, from the road. They’re hidden behind screens of trees. Small markers telling delivery trucks which road to turn onto are often the only indication that they’re there.

Decades of research and reporting since the 1990s have shown the harmful impacts of the pork industry on rural communities in Sampson and Duplin counties, where about a quarter of the population is Black, about a quarter is Latino and over 20 percent of residents live below the poverty line. Manure sprayed on agricultural fields drifts into people’s homes, contaminating them with dangerous bacteria. Phosphorus and nitrates from wastewater seep into the groundwater, poisoning local rivers and drinking wells. Hog manure lagoons also drive climate change, releasing methane, a greenhouse gas more than 80 times more potent than carbon-dioxide over a 20-year span, into the atmosphere.

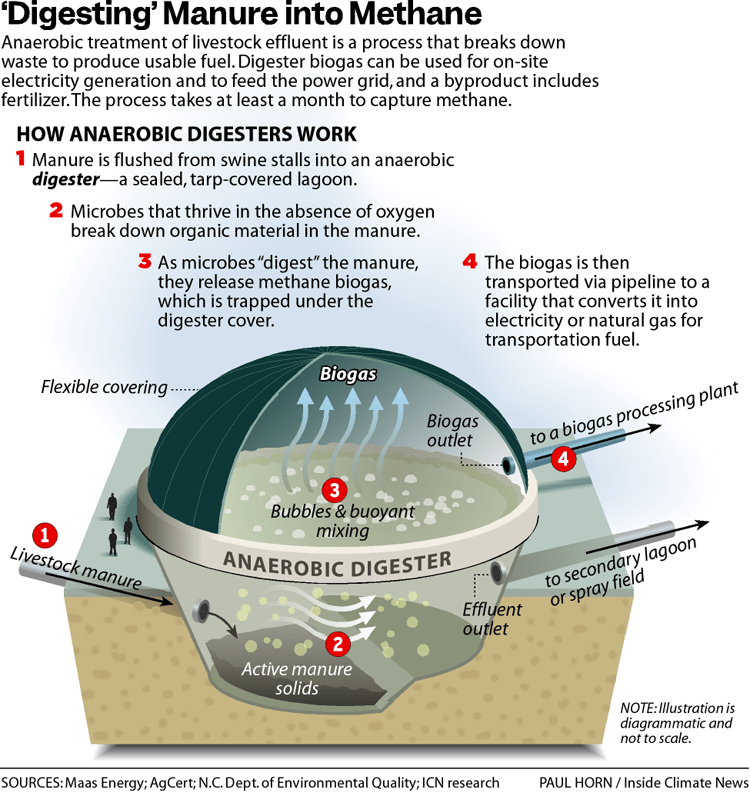

Biogas production, where farmers install methane-trapping devices known as digesters over their manure lagoons and turn the captured gas into fuel, is promoted by the pork and biogas industries, and utilities, as a way to address some of these problems—namely, the methane emissions and noxious odors from manure ponds.

“Few technologies can achieve so much good, so broadly across the community,” said Aaron Ruby, a spokesperson for Dominion Energy, a partner on the Align RNG project, a $500 million joint venture between the utility and the agricultural conglomerate Smithfield.

But since the technology has started becoming more prevalent in the region, it’s spurred new concerns among local residents.

“Communities have been suffering with the swine CAFOs for many years,” said Hall. “Whenever you begin to talk about biogas, then it just further embeds the problem.”

Advocates say that instead of reducing the number of hogs on farms, or encouraging cleaner alternative manure management systems to reduce air and water pollution, biogas production locks in the current manure lagoon system with all its potential for groundwater seepage and spills during floods. And while covering lagoons to capture methane can potentially lower greenhouse gases and pathogens, it alone does nothing to limit many of the other pollutants in hog waste, like fine particulate matter, nitrogen, and phosphorus, which still get sprayed onto nearby fields.

Some studies have even shown that digesters, depending how the devices are operated, can increase livestock waste’s releases of ammonia, a toxic gas linked to 12,400 deaths in the U.S. per year.

The United States Department of Agriculture warns that the methane capture process can exacerbate certain water quality issues by increasing the water-solubility of nitrogen in livestock waste. That raises the risk of nitrate contamination of drinking water which is linked to miscarriages and infant mortality and is a particular concern in an area where most residents draw their water from wells.

“We’ve been using the term ‘pollution swapping’ to acknowledge that this is a technology for which there’s evidence that it may reduce some pollutants while also making others worse,” said Brent Kim, a scientist at the Johns Hopkins Department of Environmental and Engineering who was part of a recent literature review that concluded digesters should not be promoted as a manure management and energy solution.

Digesters can also introduce new pollutants when they flare, or burn excess biogas, he added. “You might get byproducts like nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, particulate matter and other things that pose respiratory risks for people.”

Biogas Spreads Controversy East and West

All the way across the country in California, a program called the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) has long been a point of conflict between environmental justice groups, state air regulators and the renewable natural gas industry, especially when it comes to its incentives for dairy and swine biogas.

The program launched in 2012 with the aim of reducing transportation emissions in the state. It sets an average, gradually lowering carbon intensity threshold for fuels, and requires higher carbon fuel producers, like oil refiners, to buy credits from lower carbon fuel producers, such as solar developers or companies that make biogas from livestock and landfill methane. The expectation is that the alternative fuels will displace fossil fuels in the mix over time.

Dairy and swine biogas generates about a fifth of the credits in the program, earning hundreds of millions in subsidies each year.

The state says the program as a whole has reduced the carbon intensity of the fuel mix by 15 percent since it launched, and California dairy farmers say it provides them with the money they need to install methane capture devices to lower their climate impact, technologies for which there aren’t many other funding streams available.

“This is not only counterproductive and a distraction from real climate solutions. It’s also having serious environmental and public health consequences for communities across the country.”

— Amanda Starbuck, Food & Water Watch

But environmentalists and environmental justice advocates say the program vastly overcredits CAFOs for these reductions, diverting precious resources from electrification to reduce fossil emissions toward a fuel that may exacerbate local pollution around farms and still emits carbon dioxide and other harmful pollutants when combusted in trucks and buses.

Even more egregious, they say, is the fact that the program allows farms in Wisconsin, Texas, New York, Missouri and several other states to sell biogas credits into the California market for fuel that never makes it into California pipelines. About 45 percent of the biogas credits in the program go to 196 out-of-state farmers, according to the environmental group Food & Water Watch.

“This is not only counterproductive and a distraction from real climate solutions. It’s also having serious environmental and public health consequences for communities across the country,” said Amanda Starbuck, the group’s research director, in a statement.

Last year the program accepted credits for the first time from dairy farms in Iowa, where state law allows dairy farms to exceed established herd limits if they install methane capture devices on their manure lagoons. One Iowa farm that entered the program leaked over 375,000 gallons of manure from a digester lagoon into a nearby creek in 2022.

And 2025 was also the first time the program touched the epicenter of pork production—North Carolina.

Who Is Buying Biogas?

Years before the LCFS existed, utilities in North Carolina were required by a 2007 state law to source some of their power from renewable sources, including 0.2 percent from swine biogas by 2018. It’s the only state in the country that mandates sourcing electricity from animal waste.

Since the law passed, a handful of North Carolina farmers and project developers have earned income from installing digesters, which look like domed tarps, over swine lagoons, and using the captured methane gas to power on-site generators to produce electricity. They sell the electricity to local utilities, but several deadline extensions later, the utilities aren’t even close to reaching their biogas targets.

“That speaks to how expensive the technology is, how difficult it is to get off the ground,” said Blakely Hildebrand, a lawyer with the Southern Environmental Law Center, or SELC, which has represented groups suing the state over digester permits.

More recently, larger-scale projects to collect methane gas from farms and refine it into renewable natural gas that can be injected directly into pipelines have garnered interest from developers and utilities. In 2018, a project called Optima KV in Duplin County became the first in the area to do that, injecting RNG produced from a cluster of five Smithfield swine farms directly into a pipeline owned by Piedmont Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Duke Energy. Purchasing the gas to use in its power plants earns the utility renewable energy credits that count toward its requirements under the 2007 law.

Around the same time, a company called Carbon Cycle Energy was promoting its own partnership with Duke to provide renewable energy credits for biogas made from swine and food waste in Warsaw, although the build-out was delayed several years. And Duke in 2023 signed a 15-year renewable energy credit agreement with a project called Montauk Renewables in Sampson County that is currently under construction at the site of an old furniture factory in Turkey.

Dominion and Duke did not answer questions about if and how the Align RNG project ties into their state-mandated renewable portfolio targets. But the project has another deep-pocketed funder—California, which is directing subsidies towards biofuel production in North Carolina to help meet its transportation emissions targets.

Smithfield and Dominion did not respond to requests for comment as to how important the California credits are to their operation and whether or not they had them in mind when they began to develop their project as a joint venture in 2018.

They first submitted paperwork to sell credits into California’s transportation emissions trading market in August 2023, and their full application was finalized in March 2025.

But analysts and economists say the program has been integral to getting dairy and swine manure biogas projects off the ground nationwide.

“The cost of building and operating digesters is on the order of nine to ten times the cost of producing natural gas just by pulling it out of the ground. So it only is going to make economic sense with policy help,” said Aaron Smith, a professor of agricultural and resource economics at the University of California, Berkeley.

He said at the moment, the two main sources of policy help nationwide are the federal Renewable Fuel Standard, which credits farmers for producing biogas, and the LCFS in California, which contribute about equally to the subsidies producers can get.

“In North Carolina, companies would be making a decision whether they’re getting more value out of the LCFS versus out of the state program,” he said.

A Civil Rights Complaint Against California-Backed Digesters

The California-funded Align RNG project sits at the center of the biogas debate in eastern North Carolina.

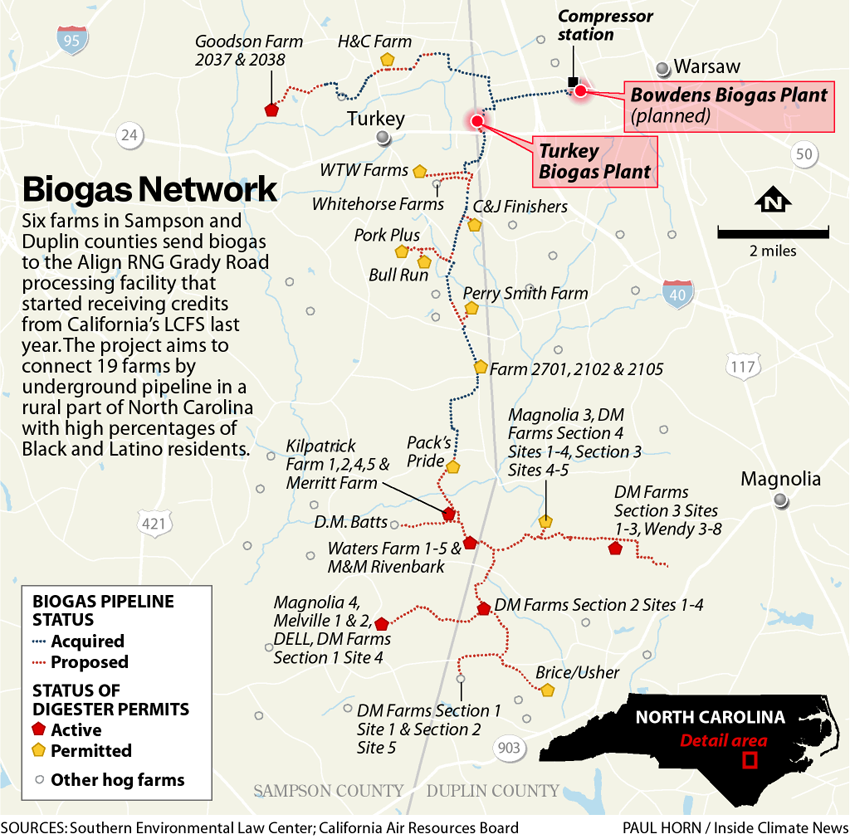

The project aims to connect 19 hog farms via 30 miles of pipeline to a central processing facility known as the Grady Road Project, which came online in November 2022.

Six of the farms are already hooked up to the project.

Located in a 13-mile radius around the facility, the farms are all owned by or on contract with Smithfield, a Chinese-owned company that’s the world’s largest pork producer and processor and contracts with about 1,000 farms in the state.

Three of the farms—the Kilpatrick farm, M&M-Waters farm and Goodson farm—are owned by Murphy-Brown LLC, a subsidiary of Smithfield. The other three—the Dell farm and two DM farms—are owned by Ironside Investment Management, part of a trust created by Murphy-Brown’s founder, Wendell H. Murphy, which contracts with Murphy-Brown. Each farm has between about 10,000 to 20,000 hogs.

The farms send their raw biogas via underground pipelines to a compression facility, where it’s transformed into biomethane to meet utility pipeline specifications and injected into a Piedmont Natural Gas pipe. The fuel powers homes and businesses in the area, while the “environmental attributes” are sold separately to offset transportation emissions across the country in California.

The project claims it will eventually be able to capture 142,000 metric tons of methane each year, the equivalent of taking 30,000 cars off the road.

But in 2021, as the Grady Road Project was being developed and farms were starting to install digesters over their manure lagoons, two groups, the Environmental Justice Community Action Network, or EJCAN, and Cape Fear River Watch, sued the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) over its permitting of digesters at four farms, three of which are currently selling credits into the LCFS.

As is common practice when installing digesters, the farms that participate in the Grady project cover their original manure lagoons to capture methane and then pump the remaining wastewater to other open lagoons built to store post-digester waste. That waste is ultimately sprayed onto fields.

The groups alleged that digester waste produces more harmful ammonia emissions and contains phosphorus and nitrogen in more water-soluble forms than waste stored in conventional lagoons. They argued that the state failed to consider waste systems that would be less harmful to health and have fewer environmental impacts when they granted the digester water permits.

“These digesters leave in place the harmful lagoon and spray field system, and digesters, without doing anything else, can exacerbate the pollution problems associated with industrial animal agriculture,” said Hildebrand, the lawyer with the Southern Environmental Law Center, or SELC, which represented the groups. “The state did nothing to address that.”

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowSELC also filed a Title VI Civil Rights Act complaint with the Environmental Protection Agency against the DEQ on behalf of the Duplin County NAACP and the North Carolina Poor People’s Campaign. They said that in granting the four permits, and then the following year creating a statewide general permit for digesters that streamlined approvals for similar projects, the state was discriminating against people of color.

“There’s pretty ample evidence that industrial hog operations and the pollution disproportionately impact Black, Latino and Native American communities in eastern North Carolina,” said Hildebrand. “Based on our analysis, these new permits were also disproportionately harming communities of color.”

In 2022, the state’s chief administrative law judge, a former DEQ secretary, sided with the agency in the legal case over the digester permits in the New Hanover County Superior Court. But the EPA decided to investigate the Title VI complaint, and that probe remains open. In 2022 the agency said it commenced “informal resolution agreement discussions” with NC DEQ. The EPA press office declined to comment on the case.

Kemp Burdette, the Cape Fear riverkeeper who was also involved in the lawsuits, said he no longer bothers testing the water quality in Stewart’s Creek, which runs near the farms, because of how contaminated it is year after year. He said he wasn’t aware until ICN reached out that California’s LCFS program was one of the funding vehicles behind the digesters.

“I guess they think they’re doing the right thing by buying swine biogas credits in North Carolina,” said Burdette. “But all they’re doing is shifting the burden to the poorest, most desperate North Carolinians.”

A spokesperson for the California Air Resources Board didn’t answer the question of whether CARB knew about the civil rights complaints against digester permits for the Kilpatrick, Goodson and Waters farms when it certified the Align RNG project for credits. But she said that the agency could revoke the credits if the facility was found to be in violation of any laws.

“CARB evaluated the LCFS pathway applications associated with the RNG project based on applicable LCFS pathway certification requirements,” said spokesperson Lindsay Buckley. “CARB may invalidate LCFS credits generated or transferred in violation of laws, statutes or regulations other than the LCFS itself.”

More Pipelines Could Be Coming

On a rainy day, Sherri White-Williamson drives east from her office in an old armory in the town of Clinton, in Sampson County, and down Highway 24 to point out some of the biogas buildout in the area.

White-Williamson, executive director of the EJCAN group that sued the state over digester permits in 2021, has been organizing against biogas for the past six years, since around the time when Align RNG’s first air permit hearings were announced in 2020.

“We went out to get people engaged to be on that public comment call, especially people that were right across the road and down the road from the Align facility,” said White-Williamson, who was working for the North Carolina Conservation Network at the time. “What we learned was that no one realized what it was.”

Beyond concerns about pollution from manure lagoons and digesters on farms, White-Williamson says residents are worried about pollution from the biogas pipeline and processing infrastructure itself.

According to the Align RNG’s air quality permit, the Turkey facility plant could emit 64 tons to 220 tons of pollutants each year. Last year, when White-Williamson brought a group of EPA officials to tour the area, they stood in front of the processing plant for about 10 minutes while gas flared from the facility, releasing pollutants like sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, which can cause respiratory issues, into the air.

Behind a chain link fence five miles down the road loom the three towers of Carbon Cycle Energy biogas facility, which had a spill two summers ago.

As climate change intensifies storms and makes them more frequent, the chances of accidents increase.

“When you’re concentrating that much methane in pipelines and storage tanks, there are risks of fires and explosions,” said Kim, the researcher at Johns Hopkins.

EJCAN has limited resources to learn more about the digester and biogas projects in Sampson and Duplin counties, especially after the Trump administration cut a $417,000 research grant the nonprofit was a part of to study the health impacts of biogas production in the state.

And the funding for the projects cropping up in the region is opaque. Utilities in North Carolina report to the North Carolina Utilities Commission on their plans for biogas sourcing but the details are redacted from public documents. And while CARB posts new LCFS fuels pathways on its website, it shares limited information about what the other subsidies and credits projects might be receiving.

The LCFS application for the Align RNG Grady Road project notes the project earns credits from the federal Renewable Fuels Standard Program, which sets minimum volumes of renewables in transportation fuel and pays developers for delivering it.

The project also sells North Carolina renewable energy credits and carbon credits for electricity production, and the application says the gas used to make electricity is accounted for separately from the gas sent to the refining facility that gets credited by California’s program.

Ruby, the Dominion spokesperson, said the amount and cost of the credits, as well as what buyers might be purchasing from the facility, is “proprietary business information.”

Dominion and Smithfield didn’t respond to a request for comments as to whether they were seeking additional certifications from the LCFS as they look to connect 13 more farms to the Align RNG project. They also didn’t say what funding streams they plan to use as they look to build a second processing facility in Bowdens, just north of Warsaw, that would serve 35 more farms, according to the Align RNG website.

CARB didn’t say whether it was working on certifying any more fuel pathways from North Carolina swine farms.

But it’s likely more North Carolina agribusinesses and developers will be seeking credits from the program. As of August 2025, the state already has 30 permit applications for digesters waiting in the queue, in addition to the 59 already permitted, most of them in Duplin County. Smithfield has announced it wants digesters on 90 percent of its farms in the state.

The uncertainty over where the money is coming from has local residents and advocates on edge.

“If there’s this boom, then what I want to know is, what other farms are connected to the California carbon trade?” said Hall, at REACH.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,