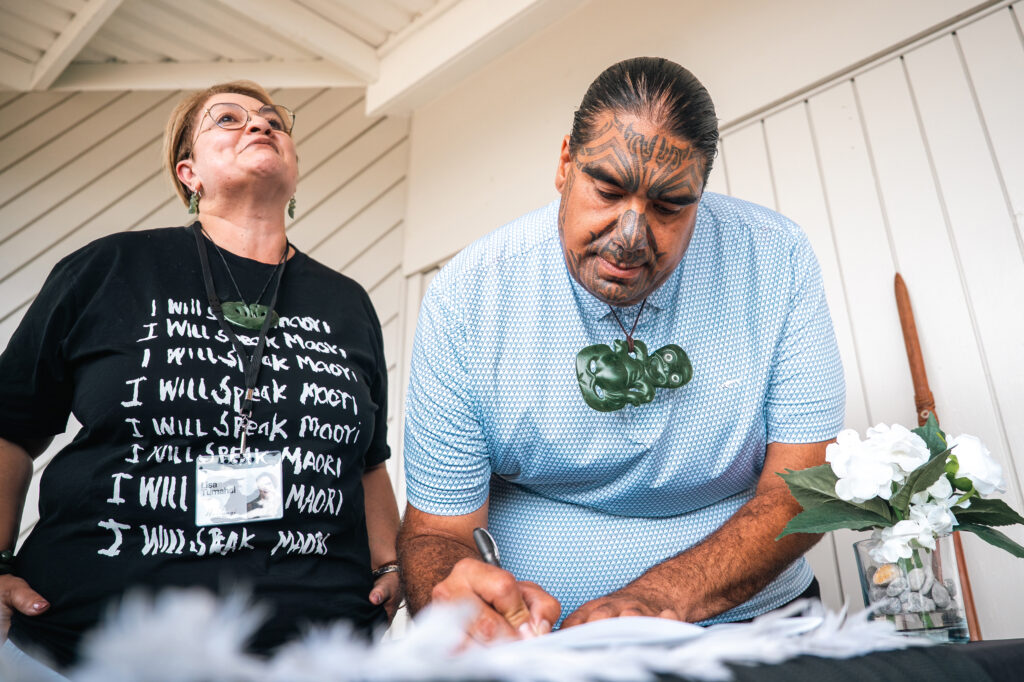

In one of his final acts before his death in 2024, Māori King Tūheitia Pōtatau Te Wherowhero helped galvanize Pacific Indigenous leaders to sign a landmark declaration recognizing whales’ rights.

Now that effort could shape national law: New Zealand legislators this month introduced a bill grounded in the declaration, affirming whales’ rights to migrate, maintain natural behaviors and culture, and live in a healthy environment with damaged habitats restored.

The bill, introduced by a member of Parliament from the Green Party, Teanau Tuiono, would recognize whales as legal persons, a status already held by corporations and other nonhuman entities. The legislation would require the government to consider whales’ rights when regulating activities that affect them and their habitats, including shipping, fishing, deep-sea mining and coastal development.

Such proposals are part of the broader rights-of-nature movement challenging the conventional legal view of nature as a collection of “things” to be owned and exploited, much like microwaves or cars. Unlike traditional regulations that try to cap the harm humans can cause, a rights- of-nature approach typically creates an affirmative duty to protect the natural world’s biological integrity, treating it as kin, not a commodity—a concept drawn from many Indigenous cultures.

Shortly before his passing, the Māori king met with Green Party lawmakers and spoke about the He Whakaputanga Moana (Declaration for the Ocean) treaty.

“He asked if we could help, and this is us honoring that conversation,” said Tuiono, who is also Māori. “This is about honoring his legacy.”

It’s uncommon for a treaty created by Indigenous nations to drive national law, legal experts note, making He Whakaputanga Moana’s impact on New Zealand a striking reversal of the usual top-down approach to environmental governance.

And it could be just the beginning.

“It Was Always About Implementation”

The New Zealand legislation is one piece of a wider effort to implement the declaration, guided by the Hinemoana Halo Partnership Fund, an Indigenous-led conservation organization that helped create it. Co-chair Lisa Tumahai said the group has spent the past year identifying ways to translate the declaration into action across multiple countries.

“This was never just symbolic—it was always about implementation,” Tumahai said.

This month, Hinemoana Halo announced another step: a partnership with legal experts from New York University’s More-Than-Human Life (MOTH) Program and scientists from the Cetacean Translation Initiative (Project CETI). With those groups on board, implementation efforts are accelerating, Tumahai said.

The collaboration emerged from conversations between MOTH founding director César Rodríguez-Garavito and Hinemoana Halo representatives at the United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice last year. At the time, MOTH’s lawyers, who specialize in rights of nature law, were already working with scientists from Project CETI to explore how emerging research on whale communications could support legal arguments for whales’ rights.

From the outset, all three groups agreed that Indigenous leadership would set the direction, with law and science supporting that foundation.

“The strength of the declaration lies in its grounding in Indigenous values—reciprocity, responsibility and ancestral relationships with ocean beings like whales,” Rodríguez-Garavito said.

Those attributes, he said, mark a departure from earlier whale protection efforts dating back to the 1970s. Laws like the Endangered Species Act and treaties like the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling are powerful conservation tools, but they generally position whales and marine ecosystems as resources to be managed for human benefit.

Despite those protections, the outlook for whales has worsened in many ways. The growing global shipping fleet causes tens of thousands of deadly whale strikes annually. Climate change is acidifying oceans and disrupting whales’ food supplies. And each year, hundreds of thousands of cetaceans die painful deaths from entanglement in fishing nets.

He Whakaputanga Moana starts from a different perspective, advancing a relational worldview that recognizes whales as ancestors with their own spirit and essence—a perspective supported by science. Whales and humans share a common ancestor from about 90 million years ago.

“We recognize the interconnectedness of all things, understanding that the ocean’s breath is our own,” the declaration says.

That conceptual shift, and the rights-based laws emanating from it, carry legal and political consequences. It can unsettle industries built on extracting value from the ocean.

Still, the appetite for rights of nature laws is growing amid a wave of legal victories and worsening climate change, environmental degradation and species declines. Over the past two decades, hundreds of related laws, court rulings and declarations have emerged worldwide, many led by Indigenous peoples and organizations.

MOTH has helped support some of those developments amid years spent working alongside Indigenous communities in Latin America. In Ecuador, where nature’s rights are constitutionally recognized, courts have issued rulings enforcing the rights of ecosystems and wildlife against government and corporate projects. Rodríguez-Garavito said similar advances could emerge from the partnership with the Hinemoana Halo fund.

“Our role,” he said, “is to help translate the declaration’s principles into legal pathways that can be pursued at both domestic and international levels.”

A Pan-Pacific Vision

To spur action, Hinemoana Halo is reaching out to countries and communities along whales’ migratory routes through the Pacific—from the Cook Islands to Tonga, Hawaii and Alaska. Species such as humpback and gray whales travel thousands of miles across a patchwork of national jurisdictions and the high seas, which lay beyond nations’ exclusive economic zones.

“We know the significant challenge we have ahead of us with international waters and many nations and countries, but you don’t let that stop the vision,” Tumahai said.

That vision, she said, ignited at the global climate summit in 2023 during a meeting among Pacific Indigenous people convened by the nonprofit Conservation International.

“We looked at how we could use our influence to protect the rights of these ancestral beings,” Tumahai said, noting that some Māori organizations and iwi (tribes) had been advocating for whales for decades.

As work on the declaration began, Tumahai’s colleague, Māori leader of the Ngātiwai iwi Aperahama Edwards, traveled across the Pacific—from Tahiti to Tonga, the Cook Islands, Hawai‘i and the Marshall Islands—documenting shared cultural traditions about whales that ultimately shaped the declaration’s principles.

That includes the concepts of mana (inherent authority and power) and wairua (the spiritual essence or life force) of whales.

“Whales are lifesavers for our oceans—they are what keep things alive in our ecosystem,” Tumahai said. “Because of this vital role, they hold a high standing—a mana—that demands respect and preservation from humans.”

The declaration also talks about rāhui—a traditional form of protection that temporarily closes areas or applies restrictions to allow for healing and rejuvenation. Recognized under New Zealand law, rāhui are implemented by local iwi until habitats have sufficiently healed. Iwi in areas affected by the devastating 2016 Kaikōura earthquake, for example, did just that, giving marine ecosystems time to regenerate.

“Without it, the area wouldn’t have repopulated,” Tumahai said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThough the declaration includes language on financing mechanisms like biodiversity credits, Tumahai said Hinemoana Halo is not pursuing any tied to whales. The organization is seeking to amend the declaration to remove that possibility, underscoring that its focus is on legal recognition and protections rather than market-based offsets.

Discussions about the declaration are now crossing the Pacific, with Polynesian leaders engaging Indigenous communities in Latin America on how the framework could take hold there as well.

“A next step,” Rodríguez-Garavito said, “is fostering more of those collaborations and trust building with leaders from this side of the world and that side of the world.”

Cutting Edge Science

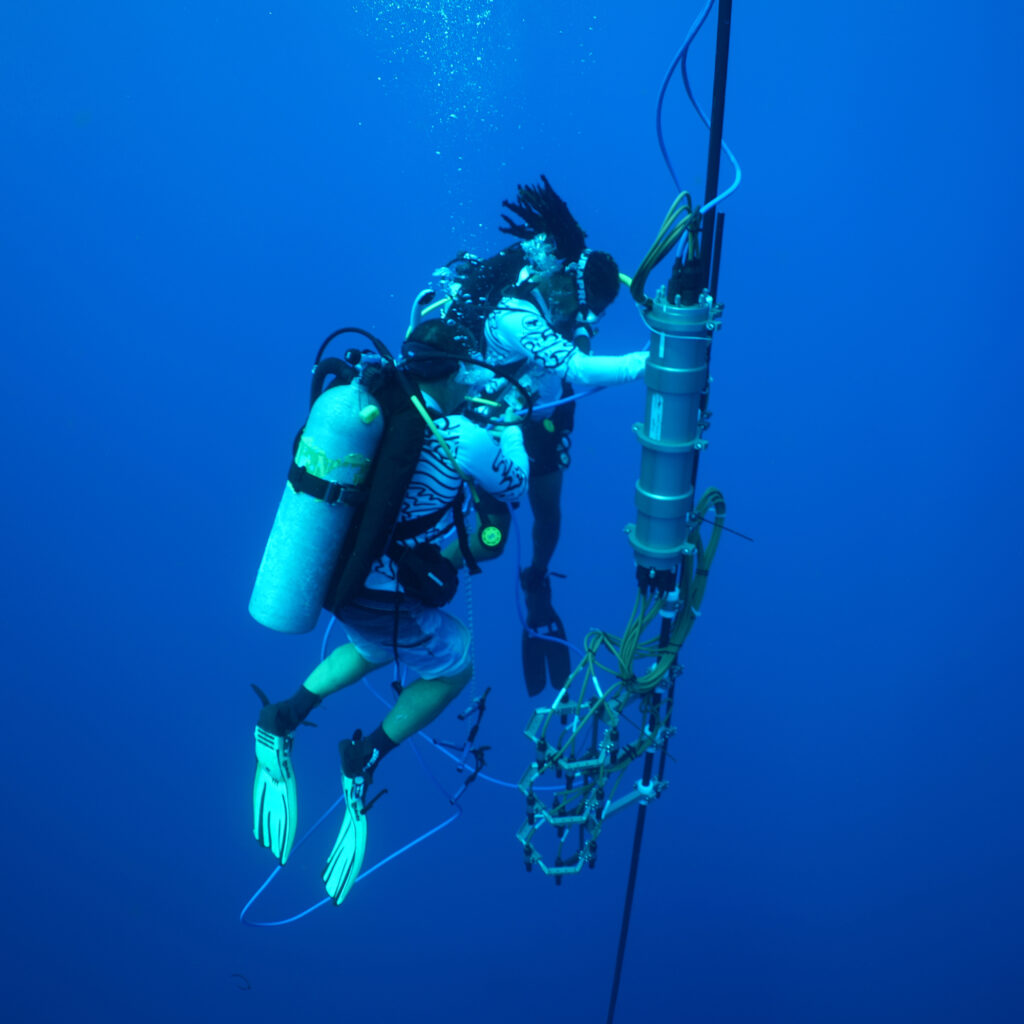

Scientific research is expected to play a central role in turning the nonbinding declaration into hard law, with courts and lawmakers relying on such evidence when deciding environmental cases and drafting legislation.

Since its founding in 2020, Project CETI has catapulted to the forefront of whale science, redefining human understanding of these cetaceans by mapping their communications. The nonprofit’s researchers use noninvasive acoustic recording technologies and artificial intelligence to analyze sperm whale vocalizations, work that has revealed a sperm whale alphabet and socially meaningful communication patterns. That positions sperm whale communication closer to human language than that of any other species examined to date, according to the researchers.

The findings can help demonstrate when human activities, such as ship noise, harm whales by tracking changes in their voice signatures.

Project CETI’s founder and president, David Gruber, is among many scientists now backing the rights of nature movement because they see such laws as a scientifically accurate reflection of how ecosystems function and wildlife behaves. Gruber pointed to the declaration’s recognition of whales’ right to culture and their complex social structures and identities.

“That’s exactly what we’re studying in Dominica: dialects, vocal patterns, even vowels and diphthongs in sperm whale communication,” Gruber said. The Caribbean island of Dominica has been Project CETI’s main research hub, though its geographic scope is expanding.

From birth, patterns of clicks, known as codas, play a key role in sperm whale culture. Calves “babble” before learning their full coda calls, much like human infants learning to speak. Females use codas to coordinate and help one another give birth and care for calves, and the click patterns convey information about migratory routes, foraging techniques and social rituals.

The declaration’s emphasis on intergenerational responsibility also resonated with Gruber, who described science as an evolving body of knowledge passed from one generation to the next, increasingly enriched by the convergence of Western research and place-based Indigenous expertise. He said this melding of systems points toward a future in which Indigenous leadership shapes how humans live alongside other species on the planet.

“Indigenous communities have listened to whales for thousands of years,” he added. Now, researchers are “bringing deep listening to Western science.”

Ushering in Ecocentrism

In New Zealand, legal personhood for the nonhuman world is not new. Māori iwi have won settlements with the government to establish recognition of the Te Urewera forest, Whanganui River and Mount Taranaki as rights-holders. Corporations, ships, limited partnerships and universities are also legal persons under New Zealand law.

For Tuiono, the lawmaker who introduced the New Zealand legislation, this first step for whales’ rights is deeply personal.

“I feel like I’m making a contribution,” he said. “That’s my main focus in politics—not for politics itself, but to do something meaningful for Māori, for my people, and for the environment.”

He was a young environmental science student when he first heard the word “anthropocentric,” meaning human-centered.

“We’ve always taken an anthropocentric view of the world, thinking it revolves around us,” Tuiono said. “We should be taking an ecocentric view—seeing ourselves as part of the web of life, not the center of it.”

Whales, he added, embody that concept. “They’re so iconic. If you look after whales, you’re looking after everything else.”

New Zealand is one of the places on Earth where the oceans are warming faster than average—34 percent faster, which is harming whales’ migration patterns, species populations and food sources.

Humans have long treated the ocean as an inexhaustible resource, Tuiono said. That mindset has consequences. He hopes the new legislation will prompt a shift in the worldview that created intersecting climate and biodiversity crises.

“It can’t be about extraction anymore. We live on a finite planet with finite resources. We need to respect the other species we share it with,” Tuiono said. “We need to care for the environment so it’s thriving—for everyone that calls this place home.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,