Devastating storms still roiling much of the American Midwest have dumped record levels of rain over the past week and caused flash flooding that has killed at least 10 people, inundated towns and highways, and forced hundreds of people to evacuate their homes. Parts of Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Arkansas and Louisiana received 10 to 15 inches of rain in the past seven days, according to the National Weather Service, resulting in record crests of numerous rivers across the central United States.

Extreme storms like these have become more common as global temperatures have risen and the oceans have warmed. Some have the clear fingerprints of man-made climate change.

“Of course there is a climate change connection, because the oceans and sea surface temperatures are higher now because of climate change, and in general that adds 5 to 10 percent to the precipitation,” Kevin Trenberth, a climate scientist with the National Center for Atmospheric Research, said. “There have been many so-called 500-year floods along the Mississippi about every five to 10 years since 1993.”

Scientists won’t know the extent to which climate change played a role in these storms unless they do an attribution study. Such analyses determine how much the rise in trapped greenhouse gases increased the odds of a single event happening. Increasingly, scientists have tried to do these studies far more quickly to spread accurate information about how climate change is affecting us today and improve longer-term forecasts and warnings.

An attribution study of last August’s deadly Louisiana’s storms—classified as a 1,000-year storm in the worst-hit areas and a 500-year storm in others—found that human-caused climate warming increased the chances of the torrential rains by at least 40 percent.

That figure corresponds to the overall increase in extreme storms in the region.

“Across the board, the United States has seen an increase in the heaviest rainfall events, and the Midwest specifically has seen an increase [in these events] of almost 40 percent,” said Heidi Cullen, chief scientist at Climate Central and a member of World Weather Attribution (WWA), a group that is developing methods to quickly determine climate change’s role in extreme weather events.

Like last summer’s downpours in Louisiana, however, the ongoing storms across much of the central U.S. are moving slowly, a characteristic that has not been directly attributed to climate change and has likely exacerbated current flooding.

The increase in extreme weather comes as record temperatures have been recorded across the planet in recent years and as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has reached unprecedented levels. The first quarter of 2017 was the second-warmest start to a year globally since the late 1880s, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Among the 17 hottest years ever recorded, 16 were this century.

Climate scientists explain that as the planet warms, evaporation increases, leading to more moisture in the atmosphere and more precipitation. Across the Midwest, upper Great Plains and Northeast, the amount of precipitation during very heavy events has increased more than 30 percent above the 1901-1960 average, according to the third National Climate Assessment.

Flooding, too, has risen in several of these regions. Storms characterized as 500-year events, meaning they have an amount of precipitation expected to occur once every 500 years, have increased. The Louisiana storms last summer had been the eighth 500-year event in the U.S. in just over a year.

Meanwhile, the storms lashing the central U.S. showed no signs of letting up Friday.

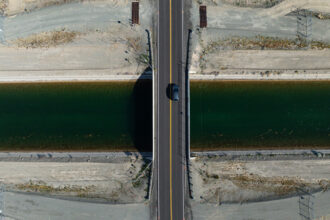

Drone footage captures widespread flooding in northeast Arkansas, the aftermath of heavy rains in the region. https://t.co/ke0cxX4hyM pic.twitter.com/W2qrFtl0jz

— ABC News (@ABC) May 2, 2017

A levee on the Black River in northeastern Arkansas gave way earlier in the week, sending the river spilling into the already-evacuated city of Pocahontas, Arkansas, (pop. 6,500). Aerial photos showed murky water covering fields and surrounding businesses and homes. Seven levees on the Missouri River have been overtopped by water and seven more have been breached. Flooding along the middle and lower Mississippi River is anticipated through at least the middle of May.

Arkansas Governor Asa Hutchinson has declared the flooding a statewide disaster. He ordered National Guard units to the area and called on the state Department of Correction to use inmate labor to load and stack sandbags.

The threat isn’t over. Flash flood watches have been issued for parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, Indiana and Ohio as rain from the slow-moving storm is expected to continue.

“We expect to see more extreme heavy rainfall events like this in the future, and, as a result, we very much need to be having a conversation about our infrastructure,” Cullen said. “Hospitals, schools, military bases will flood during these extremes. We need to do a very careful analysis of how we are going to respond to the fact that the risk is increasing.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,