This reporting was supported by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

In 2017, a Missouri-based corporation called Jaines LLC forked over $9.6 million in exchange for 110 acres of vacant buildings and cracked concrete in Janesville, Wisconsin.

The corporation was an affiliate of Commercial Development Co. (CDC), which bills itself as North America’s leading redeveloper of industrial brownfields, and the vacant lot was the former site of General Motors’ Janesville Assembly Plant, which had employed a tenth of the town’s workforce before closing in 2009.

CDC billed its purchase as the beginning of an economic rebirth, touting the site as a “strategic opportunity for new manufacturing, warehousing and logistics-related development activity.” It proceeded to demolish the plant and auction off the equipment salvaged from the site.

Since then, large piles of rubble have continued to dot the property, in violation of city ordinances, according to city manager Kevin Lahner, who reported that the company has been regularly delinquent on its taxes. The property remains under Jaines LLC’s ownership despite at least one attempt to sell it. Frustrated by the company’s lack of progress on bringing the site back into productive use, city officials moved to condemn it last year. Of CDC’s initial promises of cleanup and redevelopment, Lahner said, “the city of Janesville was sold a bill of goods when they acquired that property and now we’re trying to un-ring that bell.”

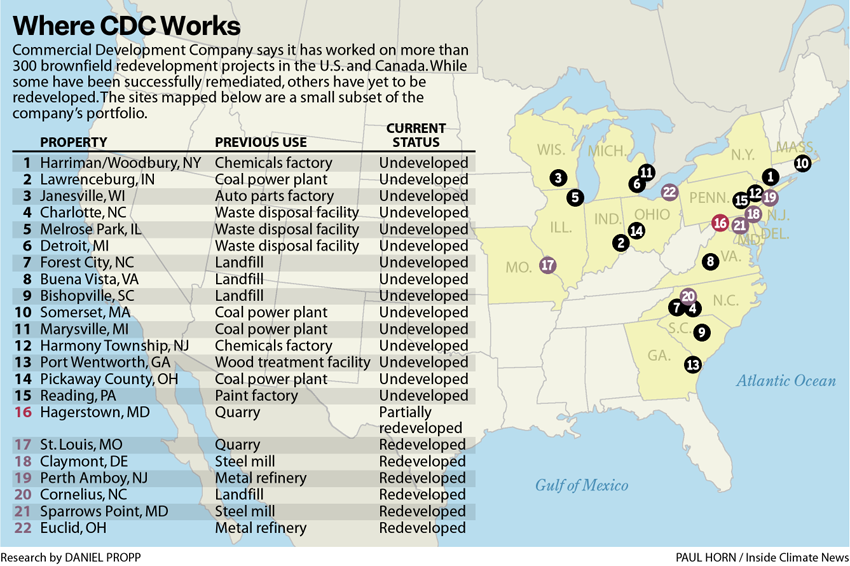

Many other properties currently or previously in CDC’s portfolio—more than 300 sites across the United States and Canada—remain similarly undeveloped. Among them are major industrial plants that were once the economic hearts of their communities, now crumbling and deserted.

In a months-long investigation—involving property records, financial filings, court records, site visits and interviews with local officials—Inside Climate News tracked down 84 properties currently or previously owned by CDC-affiliated companies. Out of this portfolio, 63 met the federal definition of a brownfield: sites where the presence of a contaminant complicates efforts at redevelopment. Represented among these brownfield sites were retired coal power plants, metal foundries, waste dumps, automotive factories and a range of other industrial facilities.

Neither CDC nor its co-principals Thomas and Michael Roberts responded to repeated requests for comment.

There is an undeniable appeal to CDC’s business proposition: An industrial operator in possession of an environmentally degraded property can unload it—either selling it for a steep discount or paying CDC to assume ownership—and, in doing so, unburden itself of the associated environmental liability. CDC, in turn, will clean up and re-sell the property to a developer, bringing in a profit and returning the site to productive use.

“The city of Janesville was sold a bill of goods when they acquired that property and now we’re trying to un-ring that bell.”

— Kevin Lahner, Janesville city manager

In reality, a property can be worthwhile to CDC even if it remains undeveloped. The money earned in exchange for assuming the property, sometimes totaling tens of millions of dollars, and the cash from auctioning off salvaged materials, also in the millions, can far exceed the year-to-year expense of property taxes, providing little incentive to undertake costly remediation or redevelopment. As a consequence, many properties—more than three-quarters of the 63 brownfield properties Inside Climate News investigated—sit undeveloped, sometimes decades after CDC acquired them.

Yet the company’s presence in legacy manufacturing hubs like Detroit, Reading and Trenton places it at the fulcrum between disuse and revival. When the company’s plans to revive neglected properties fall through, so too do the hopes of economic rebirth harbored by many in North America’s Rust Belt communities.

The Brownfield Property Brothers

CDC traces its roots to 1990, when a St. Louis-based entrepreneur named Thomas Roberts founded it as a real estate venture, after having mixed success in the demolition and waste management business. By 1995, his brother Michael had joined the company, too.

Today, the Roberts brothers sit at the helm of a company that has experienced significant growth since the 1990s. One of the company’s major success stories began in 1994, when it purchased an abandoned quarry in St. Louis. Twenty years of filling and landscaping finally enabled the site to host new development, and it is now home to an assisted living center, an apartment complex and a pair of hotels, along with CDC’s headquarters. Today, the company’s website features a client list of industrial giants such as General Motors, Shell and Westinghouse. “They seem pretty competent,” a former contractor for CDC said. “They know what they’re doing.”

But a visit to another one of the company’s brownfield sites offers a different view of what happens when CDC acquires a property—and the chain of events that often follow.

The Tanners Creek Generating Station was a hulking, 1,100 MW coal power plant that had loomed over the town of Lawrenceburg, Indiana, for more than six decades before it shut down in 2015. Like many legacy industrial sites, the land occupied by the power plant was contaminated enough to be less than useless to its owner, the electric utility AEP, prompting the company to engage CDC in a type of asset transfer called a “negative value transaction.” In late 2016, AEP paid an LLC affiliated with CDC a whopping $92 million to assume ownership of (and liability for) the property.

Negative value transactions are a recurring feature of CDC’s business model. The company and its affiliates have signed such deals with electric utilities, landfill operators, chemical manufacturers and toxic waste dump owners, taking in tens of millions of dollars in exchange for the properties and their associated liabilities. In other cases, such as a metal refinery in Washington and a chemical plant in Georgia, CDC purchases properties out of bankruptcy proceedings, allowing it to assume ownership at a low price.

As in Janesville, ownership of the Tanners Creek site was transferred to a limited-liability corporation with no other holdings. In fact, nearly all of CDC’s brownfield acquisitions are owned by LLCs whose assets are carefully limited. This practice insulates CDC from liability and allows it to cap the amount of money it might be compelled to spend on cleanup or environmental damages. In some cases, local officials seeking information about (or contact with) the new owner may not grasp the relationship between CDC and its affiliate LLCs. A town official in Lawrenceburg reported being unaware of the local affiliate’s ties to CDC.

The year after CDC acquired Tanners Creek saw a flurry of salvaging, demolition and cleanup. In a chain of events often repeated across its portfolio, CDC affiliate Industrial Asset Recovery LLC retrieved any valuable equipment that could be recovered from the site—including copper wire and transformers—and auctioned it off, earning well over $1 million, according to court records. CDC affiliate Industrial Demolition LLC then dismantled the remaining structures on the property. Finally, CDC affiliate EnviroAnalytics Group began remedial work, including capping ash ponds and redirecting surface water.

Having undertaken remedial work, CDC marketed the land that had once housed the power plant, billing it as “a rare opportunity for an industrial user.” According to property records, CDC has sold its holdings to industrial developers, land conservancies and municipal governments, sometimes within two years of acquiring them. In the case of Tanners Creek, however, reuse proved more elusive. A provisional plan to turn the site into Indiana’s fourth port—a huge economic windfall for Lawrenceburg—fell apart in 2020 when an environmental survey turned up evidence of toxic chemicals—including arsenic, lead and boron—as deep as 40 feet beneath the surface. “Remediation work would take years to complete on a significant portion of the land, rendering the site economically unviable as a port facility at this time,” Ports of Indiana concluded.

The undeveloped acres in Lawrenceburg have counterparts across the country. Of the 63 brownfield sites Inside Climate News investigated, only 15, fewer than one in four, have been fully redeveloped since CDC acquired them, with some remaining vacant for a decade or longer.

Examples of these undeveloped properties include:

- A retired coal power plant in Marysville, Michigan. A CDC affiliate acquired the site in 2014, vowing it would soon host “a 100-room hotel, retail/office, restaurants, and marina with pedestrian walkways.” While marketing materials claimed the property was “on track to be repurposed as a new community asset in 2017,” Marysville zoning administrator Sean Quain reported that there had been no redevelopment activity on the site. He characterized the redevelopment plans as “wishful thinking and maybe some promises that weren’t upheld.”

- A former wood treatment plant near Savannah, Georgia. CDC acquired the site through an affiliate company in 2014 and listed it for sale in 2016, though remediation work continued into 2021. Despite pledging to “clear the way for a new port-related redevelopment,” CDC has not managed to sell the site, a local planning official said.

- A former chemical plant in Harmony Township, New Jersey. A CDC affiliate acquired the site in 2011 and has yet to demolish the building, which is now overgrown and partially collapsed.

- A retired coal power plant in Pickaway County, Ohio. A CDC affiliate acquired the site in 2016, with a spokesperson for the company calling it “the first step toward repurposing this property and returning it to productive use.” The plant has since been demolished, but the property remains undeveloped. “It’s still sitting vacant,” said Tim McGinnis, Pickaway County’s director of development and planning, noting that there were “some federal EPA restrictions on the site” that made redeveloping it more difficult.

- An abandoned paint plant in Reading, Pennsylvania. CDC assumed ownership in 2016, saying, “Our acquisition of this under-utilized asset is the first step toward repurposing it for new development and improved utilization.” Today the site sits vacant and dotted with rusting barrels, though the Reading Zoning Hearing Board approved an application to build a strip mall there in August 2024.

Legal and Lucrative

Brownfield redevelopment is an inherently tricky process. Large industrial sites can harbor a nasty cocktail of contaminants—in the soil, surface water and groundwater—that require complex procedures to remediate. This specialized expertise, along with the federal government’s relatively stringent standards for full cleanup, can run up a sizable bill. Large remediation projects can cost as much as $200 million and timelines can stretch far beyond original projections. In the case of a retired automotive plant, for example, the median time to remediate and redevelop a site is 6.5 years, according to Bruce Rasher, the redevelopment manager for the RACER Trust, which administers retired GMC facilities.

CDC has, for its part, completed several successful redevelopments in spite of these difficulties. In addition to the retired quarry that now hosts its headquarters, the company has also reclaimed a former steel foundry in Delaware, now a transit terminal, and a former metal refinery in New Jersey, now a warehouse.

But the surfeit of sites in the company’s portfolio that continue to sit vacant tells another side to the story—of an ambitious and entrepreneurial company operating in the gaps of U.S. environmental law.

“As a general matter, the fact that a site is contaminated doesn’t mean it has to be cleaned up,” said Michael Gerrard, director of Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law. “If a site is a Superfund site [meaning it is found to pose a danger to nearby communities], the Environmental Protection Agency or the state will require a cleanup. … But it only has to be cleaned up if the government says so or if it is going to be redeveloped.”

David Altman, president of environmental law firm AltmanNewman, says that the duties of the property owner depend heavily on the property transfer agreement through which they acquire it. These agreements specify the cost of the asset transfer and the obligations of the new owner, but many do not see the light of day.

“Some property owners will do anything they can to keep the transfer agreements secret,” said Altman. “And such secrecy is a big problem for communities because they don’t have transparency about what the owner is going to do with the property.”

Inside Climate News was able to access two such agreements—for a portfolio of chemical disposal sites and a portfolio of landfills—outlining the terms under which CDC affiliates acquired the degraded sites. In both, a CDC affiliate agreed to clean up the site and assume liability for past and ongoing pollution in exchange for a fee and an additional sum, held in escrow, to cover cleanup costs.

Theoretically, Altman and Gerrard note, the asset transfer agreement should invite scrutiny from environmental regulators.

“Any contaminated site is going to have a set of permits associated with it, with different permits or consent decrees for different types of properties,” said Altman. For a contaminated property to change hands, these permits or consent decrees would need to be transferred to the new owner, something that often requires approval from the state, he said.

“That’s where a responsible state regulator would take a look at the track record and assets of the new owner and ask, ‘Can they be trusted to clean up this property?’” Altman said. “But in some states—I don’t know why—these agreements aren’t getting that level of scrutiny.”

“Some property owners will do anything they can to keep the transfer agreements secret. And such secrecy is a big problem for communities because they don’t have transparency about what the owner is going to do with the property.”

— David Altman, AltmanNewman environmental law firm

If state oversight is limited or absent and asset transfer agreements are kept secret, it can be nearly impossible for nearby community members to motivate a cleanup.

Once a property owner has met the requirements of the agreement—and absent a Superfund designation or a formal redevelopment plan—economics often point to disuse over redevelopment.

At the Tanners Creek site, for instance, a complete decommissioning and remediation job could have cost $120 million, based on research by Resources for the Future on coal power plants of a similar size, with a significant chance of escalation should new contamination be discovered—a sum far in excess of the $92 million CDC earned by taking over the site.

This business has proved lucrative for the Roberts brothers. Though the extent of their wealth is not fully known, they are major political donors in Missouri and own golf courses, vacation homes, horse farms and private jets in the state. The brothers keep a low profile, though occasional property disputes have landed them in the local news.

Concerns Continue After Sales

CDC’s business model can get messy, even when redevelopment is successful.

In 2018, CDC affiliate Brayton Point LLC acquired an eponymous retired coal power plant in Somerset, Massachusetts, from electric utility Dynegy, and publicly pledged to “reposition Brayton Point as a world-class logistics port, manufacturing hub, and support center for the emerging offshore wind energy sector.”

Following the Trump administration’s moratorium on offshore wind, however, CDC scrambled to find a new use for the site, ultimately leasing it to a New Jersey-based scrap metal business.

Local residents complained that the operation was creating a cloud of dust over nearby neighborhoods, leading the town’s Zoning Board of Appeals to issue a cease-and-desist order, which was upheld in 2022 by a local judge.

Criminal charges filed by the town in January 2024, however, allege that the CDC affiliate continued to allow trucks to haul scrap, violating the cease-and-desist order 11,561 times over the course of 482 days, with the town seeking repayment of $3.5 million in unpaid fines. Lawyers for CDC contested the amount owed and the case went into settlement negotiations in August. Meanwhile, electrical cable manufacturer Prysmian is weighing whether to move forward with plans to construct a $300 million facility on the site.

CDC’s approach to brownfield acquisitions has landed it and its affiliates in court on numerous occasions. In 2013, for example, CDC affiliate Trex Properties LLC took over a portfolio of chemical disposal sites, with locations in North Carolina, Illinois and Michigan, in exchange for $1.8 million from the previous owner, with another $11.1 million placed in escrow to cover cleanup costs.

Over the ensuing decade, lawyers for Trex sent letters to roughly 2,000 businesses—including auto body shops, dry cleaners and print shops—that had previously availed themselves of the disposal sites, demanding that they contribute to the cleanup costs or else face litigation.

In North Carolina alone, a judge estimated that these settlement demands had earned Trex more than $8 million, or roughly five times what the company had said it would cost to clean up the site. In dismissing the case, the judge speculated that the CDC affiliate was “leverag[ing] settlements from small companies who sent waste to a licensed waste disposal facility in good faith into a profitable investment rather than pursuing bona fide claims on the merits.” The three sites remain undeveloped today.

And in 2006, CDC affiliate Environmental Liability Transfer Inc. (ELT) acquired four landfills in North Carolina, Virginia and South Carolina. The sites’ previous owner, Reeves Brothers Inc., paid ELT $10.2 million to assume liability for the sites, placing another $1 million in escrow to cover cleanup costs. In February of 2024, Reeves Brothers’ parent company sued ELT for breach of contract, alleging that it failed to adequately clean up—or pay for cleanup at—one of the sites before selling it to a developer. That case remains pending and, of the four sites, only one has been redeveloped.

If these empty industrial sites serve as case studies in unrealized promises, what happened just outside Baltimore shows how even ostensible successes can be marred by controversy.

In 2013, CDC affiliate Sparrows Point LLC purchased a 3,100-acre brownfield site (the largest in the nation at the time) east of Baltimore out of the bankruptcy proceedings of industrial giant RG Steel.

Two years later, court records indicate, it sold the site to developer Tradepoint Atlantic for $110 million. Now, a property once riddled with arsenic, ammonia and cyanide is a bustling shipping hub serving major clients like Amazon, FedEx and Home Depot.

But a slew of lawsuits tells a more nuanced story about the site’s rebirth. In 2021, Tradepoint Atlantic sued multiple CDC affiliates, claiming they failed to honor their commitment to clean up the site. The suit alleged that CDC affiliates misappropriated nearly $18 million of the $70 million set aside for remediation before declaring Sparrows Point LLC insolvent and therefore unable to pay for further cleanup. Lawyers for the CDC affiliates denied the allegations, and the suit was settled.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowA separate lawsuit filed by the city of Baltimore claimed that Sparrows Point LLC used its proximity to a municipal wastewater treatment plant to “hold hostage the City and its and Baltimore County’s inhabitants’ ability to flush their toilets, just so that Defendant may pursue its extortionate demands for more money while providing fewer services.” Company lawyers denied the allegations and the lawsuit was settled. A third lawsuit, which was settled on appeal, alleged nonpayment of an employee.

Post-hoc remediation also proved necessary in Euclid, Ohio. In 2003, CDC affiliate CDC Cleveland LLC acquired a former metal foundry in Euclid. The company retained the site for six years before selling it to a developer who has since constructed multiple industrial buildings there. Despite CDC’s claims to have “remediated the environmental issues,” a 2008 property assessment completed on behalf of the new developer found “a significant environmental condition … which required remediation prior to the site’s redevelopment.” The developer secured over $5 million in grants from Ohio and Cuyahoga County for cleanup, completing the required remediation in August 2009, six months after acquiring the site from CDC.

And in 2004, CDC affiliate Hagerstown LLC acquired a spent quarry and an adjoining plot of land in Hagerstown, Maryland. Years later, the company reported that it had “sold half the site to a developer for an industrial park and plans to reclaim the quarry.” The portion of the site on which the actual quarry sits remains vacant and flooded—and, according to county property records, owned by Hagerstown LLC—as of 2025.

Opportunities Lost

There is a fence along Highway 17 in Woodbury, New York, that seems to be disappearing into the landscape—a near-complete tangle of wisteria, mugwort and Chinese sumac punctuated sporadically by fiberglass planks and steel poles. Nestled as it is among the rolling Catskill Mountains, the property—and much of the surrounding countryside—feels equal parts bucolic and forgotten.

The overgrown fence hides the remains of the Nepera Chemical Plant, once a major employer for the region and now another undeveloped site in CDC’s portfolio. Here, as at other such properties, a negative value transaction ($5.6 million) triggered hopes of an economic revival. But a 2019 plan to turn the property into a gambling destination broke down when, in the words of a state senator who helped facilitate the deal, “the Nepera site proved to be far more contaminated than previous evaluations suggested.”

Instead of an opportunity, the property has become an albatross around the community’s neck. Lawyers for CDC have challenged the property’s valuation nearly every year since its affiliate company took over the site in 2007, pausing only when placed under moratorium by a legal settlement. Local officials note the company has not paid its property taxes in 12 years.

The town government has now spent $40,000 fighting these challenges in court, according to former Woodbury town board member Tyler Etzel Jr. Meanwhile, the adjacent village of Harriman is seeking damages from the CDC affiliate and other previous owners of the site for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) contamination—two “forever chemicals” linked to liver disease, birth defects and kidney cancer—found in its drinking well. That case is currently being litigated in state court.

The property’s unrealized potential is a source of enduring frustration for Etzel—and an example of how leaving a brownfield undeveloped can cost a community. The same qualities that made sites like the Nepera plant attractive for industrial development in the first place—proximity to highways, railways or bodies of water—make them ripe for redevelopment. New jobs and new revenues beckon when these sites are cleaned up and returned to productive use. With these material benefits come intangible victories, too. Repurposing retired industrial sites can signal the turning over of a new leaf—a community arresting its economic slide and forging a new identity.

But these prizes slip away when sites remain vacant for extended periods of time. Jobs and job seekers in search of opportunity are diverted elsewhere. Nearby property values, researchers have found, fall by 0.4 percent to 3.5 percent simply due to their proximity to a blighted site. All the while, communities live in fear of hazardous substances, the inheritance of decades of industrial activity.

In Woodbury, the lost opportunity has left a hole in the local economy that seems unlikely to be filled. Three of the six parcels that once comprised the chemical plant are now assessed at $1, rendering them effectively valueless. “It’s worth negative to me,” said Etzel, reflecting on more than a decade and a half of legal jousting and dashed hopes of revival. “Why would anybody take over these things?”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,