Global warming caused mainly by burning of fossil fuels made the hot, dry and windy conditions that drove the recent deadly fires around Los Angeles about 35 percent more likely to occur, an international team of scientists concluded in a rapid attribution analysis released Tuesday.

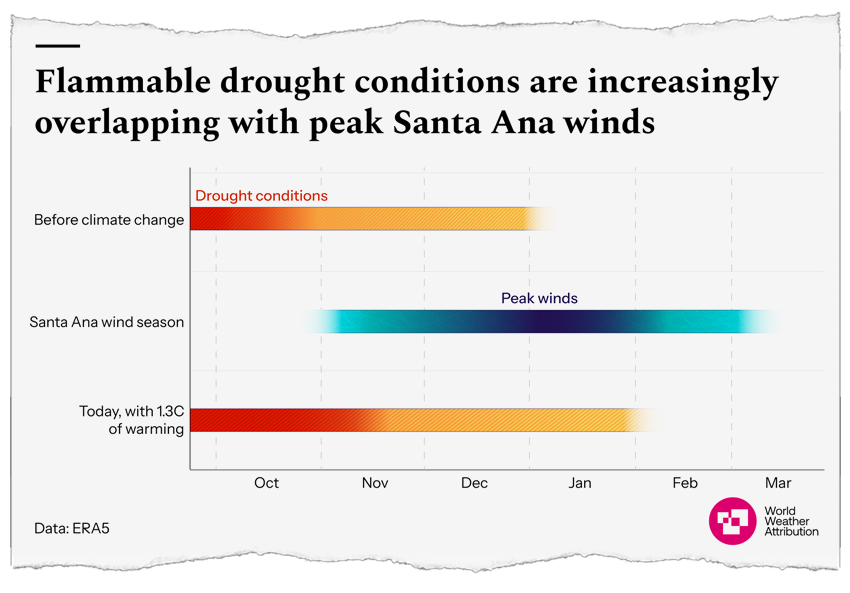

Today’s climate, heated 2.3 degrees Fahrenheit (1.3 Celsius) above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average, based on a 10-year running average, also increased the overlap between flammable drought conditions and the strong Santa Ana winds that propelled the flames from vegetated open space into neighborhoods, killing at least 28 people and destroying or damaging more than 16,000 structures.

“Climate change is continuing to destroy lives and livelihoods in the U.S.” said Friederike Otto, senior climate science lecturer at Imperial College London and co-lead of World Weather Attribution, the research group that analyzed the link between global warming and the fires. Last October, a WWA analysis found global warming fingerprints on all 10 of the world’s deadliest weather disasters since 2004.

Several methods and lines of evidence used in the analysis confirm that climate change made the catastrophic LA wildfires more likely, said report co-author Theo Keeping, a wildfire researcher at the Leverhulme Centre for Wildfires at Imperial College London.

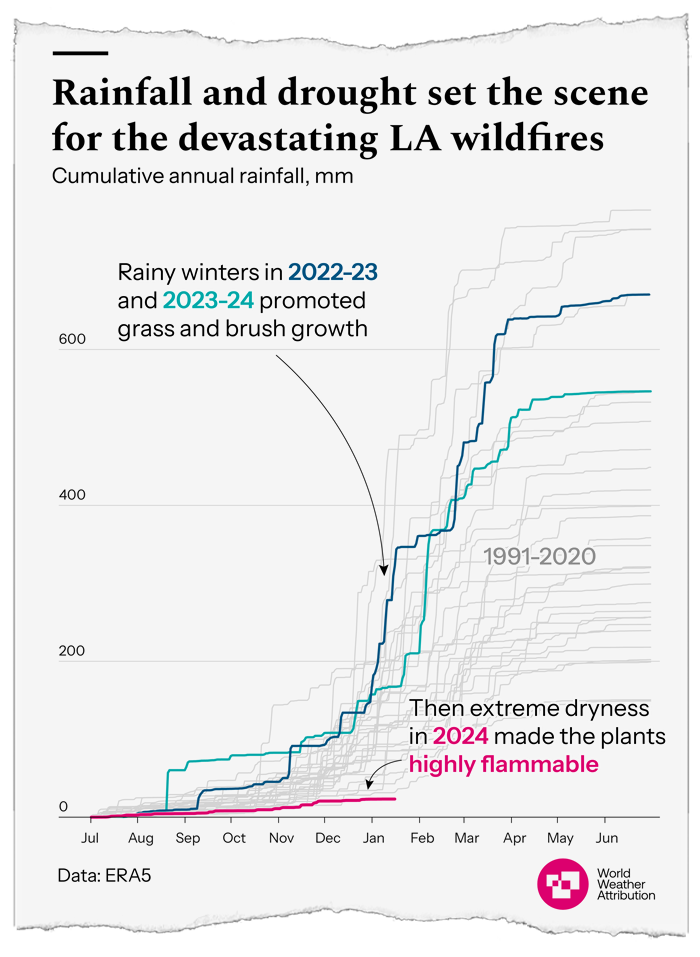

“With every fraction of a degree of warming, the chance of extremely dry, easier-to-burn conditions around the city of LA gets higher and higher,” he said. “Very wet years with lush vegetation growth are increasingly likely to be followed by drought, so dry fuel for wildfires can become more abundant as the climate warms.”

Park Williams, a professor of geography at the University of California and co-author of the new WWA analysis, said the real reason the fires became a disaster is because “homes have been built in areas where fast-moving, high-intensity fires are inevitable.” Climate, he noted, is making those areas more flammable.

All the pieces were in place, he said, including low rainfall, a buildup of tinder-dry vegetation and strong winds. All else being equal, he added, “warmer temperatures from climate change should cause many fuels to be drier than they would have been otherwise, and this is especially true for larger fuels such as those found in houses and yards.”

He cautioned against business as usual.

“Communities can’t build back the same because it will only be a matter of years before these burned areas are vegetated again and a high potential for fast-moving fire returns to these landscapes.”

The series of five major fires started January 7, and were mostly contained by January 28, when some rain and snow fell in the affected areas, but not before disrupting the lives of tens of thousands of people, and increasing long-term health risks to people who had to breathe the smoke from burning vegetation and urban structures.

After several days of official warnings about extreme fire conditions, and despite efforts to reduce the risk by shutting down some power lines, winds of up to 100 mph pushed flames, fire tornadoes, smoke and thick curtains of burning embers down through rugged canyons overgrown with dry grass, brush and trees in areas like Pacific Palisades, between Santa Monica and Malibu, as well as parts of Pasadena and Altadena. In most of those areas, fences, decks, landscaping and homes themselves were the fuel for what is projected to be the costliest climate-linked disaster on record in the United States.

The new attribution analysis was done by 32 researchers, including leading wildfire scientists from the U.S. and Europe as part of World Weather Attribution, which has studied the influence of climate change on more than 90 extreme events around the world. The scientists warned that the likelihood of dangerously fire-prone conditions will increase by another 35 percent if global warming reaches 4.7 degrees Fahrenheit (2.6 Celsius), as projected by 2100.

To evaluate how warming affected the fires, the researchers used a peer-reviewed method that combines observed weather data with climate models. The calculations show that many of the factors contributing to the conflagrations are intensified in a warmer climate.

Low rainfall in the Southern California region from October to December is about 2.4 times more likely, and fire-prone conditions in the region last 23 days longer now than in the pre-industrial climate, the scientists said. They noted that the relatively small geographic study area added some uncertainty to the equation, especially with regard to how warming affects seasonal rainfall, which has always been quite variable and is also shaped by much larger regional drivers.

Taken together, the results all indicate climate change plays a major role and the researchers are confident in the findings that warming increases the chances of such fires.

Many Other Regions At Risk

The researchers were also able to show that the fires’ impacts disproportionately affected elderly people and people with disabilities, such as those with limited mobility, as well as population groups that received late warnings. Some of those effects, they noted, will exacerbate historical economic disparities in ways that could persist long into the future.

“The neighborhood of Altadena with a large Black population was in the path of the fires, which destroyed the major source of generational wealth for many residents who had previously faced discriminatory redlining practices,” the scientists wrote in the report.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe fires exposed critical weaknesses in water infrastructure, which is “designed for routine fires rather than the extreme demands of large-scale fires, and shows the need for investments in resilient water systems and other stronger climate adaptation and emergency preparedness measures to address more frequent future wildfires.”

“This was a perfect storm of climate-enabled and weather-driven fires impacting the built environment,” said co-author John Abatzoglou, a professor of climatology at the University of California, Merced.

There are similar fire-prone communities in other regions, he added, including Boulder County, Colorado, where the 2021 Marshall fire destroyed more than 1,000 homes. Similar disasters have played out recently around the world, including the 2023 Lahaina fire on Maui’s northwest coast, and July 2024 fires in Viña del Mar, Chile.

Williams said the recent fires around Los Angeles don’t even come close to ranking in the top 10 for size.

There are many neighborhoods in Southern California nestled into the heavily vegetated mountainsides from Santa Barbara County through Ventura County, LA County, Orange County and San Diego County that could feasibly be next, he said.

“I’d say that a large number of neighborhoods are at similar risk to the small number of neighborhoods that we saw exposed to the fires this year,” Williams said.

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly stated that climate change made the conditions that drove the LA wildfires 35 times more likely. The attribution report stated that climate change made the conditions 35 percent more likely.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,