CHESTNUT, Ala.—For Valentino Thames, it’s become a routine. Just another part of everyday life.

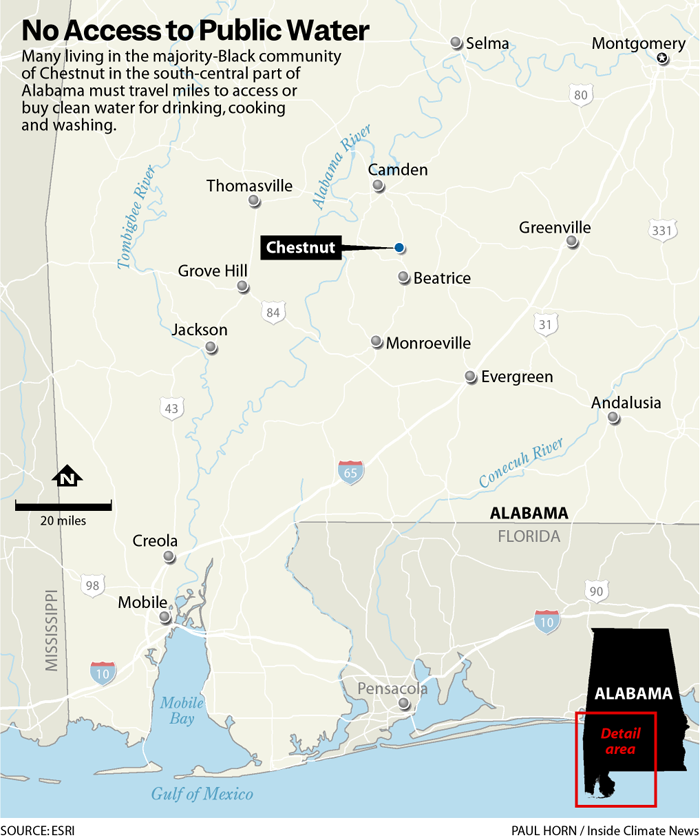

At least once a week, he makes a trip of more than 25 miles to the nearest Walmart, located in the county seat of Monroeville, to buy gallons and gallons of water—enough for him and his wife Linda to drink, cook and wash themselves until the next week, when they’ll have to do it all again.

He’s one of dozens in Chestnut, a small, majority-Black community in south-central Alabama, that lack access to public water. Like Thames, many residents are forced to travel dozens of miles to access or buy water for everything from drinking to personal hygiene, a result of private wells that are deteriorating or have in some cases fallen into complete disrepair. For years, they’ve pressured public officials without success to extend water infrastructure to Chestnut.

“I don’t understand it,” Thames said. “It seems like they come up with reason after reason to keep us from getting water. We’re trying as hard as we know how.”

Across Alabama, around 800,000 people—about 20 percent of the state’s population—rely on private water supplies, like wells, for drinking water, according to state estimates. That reality often has socioeconomic and racial implications, too.

In some places, such as Athens, just under 100 miles north of Birmingham, and Prichard, just north of Mobile, most whites have reliable municipal water and sewer service while many Black residents suffer from deteriorated or nonexistent water infrastructure.

Across the state, money and power can often determine where the water flows, experts say. And there are other risks, as a rapidly warming climate brings heat waves and drought, extreme weather and flooding. Summers, too, are simply getting hotter. As many as one-fifth of the world’s wells are at risk of drying up in the near-term, researchers have concluded.

Among public officials, Chestnut’s situation is no secret. It’s an inconvenient truth.

On Monday, residents of Chestnut attended a meeting of the town council of Beatrice, the nearest community with a municipal water supply. They hoped to get a commitment that if grant money were found for the project, Beatrice leaders would allow for a water connection and sell Chestnut residents water as they do their own citizens.

Billy Ghee represents the area on the Monroe County Commission, which is the governing body for unincorporated parts of the county like the Chestnut community. He pitched residents’ request to Beatrice town officials, who refused to allow Chestnut residents to speak. Both towns are predominantly Black.

“We’re not going to entertain questions or comments from the public,” Beatrice Mayor Annie Shelton told those gathered, including roughly a dozen Chestnut residents seated in folding chairs in the rear of the room. “This is not the time for that. This is the way it’s going to have to be done.”

Instead, Shelton allowed Ghee to take the floor.

“This is a humanitarian issue that we are dealing with,” Ghee told Beatrice officials. “And I’m hoping we can work with you all.”

Because of money made available through legislation like the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Ghee said, there may be a way to obtain grant funding to help cover the cost of extending public water access to Chestnut. Obtaining any grant money, though, would likely require the stated approval of the cooperating water authority—in this case, Beatrice. And time, he said, is of the essence.

“I don’t know how long these funds are going to last,” he said.

President Donald Trump has already issued a directive freezing government funding that called the release of IRA and infrastructure dollars into question, and though the order has since been rescinded, experts say the money may still remain in limbo and litigation as the Trump administration unfolds.

Beatrice’s water operator, Stanley Watson, spoke after Ghee on behalf of town officials.

Watson said he agreed with Ghee’s characterization of the problem and said it was one of his “longtime dreams” to extend water supply to Chestnut.

“But it’s not feasible,” Watson said. “The money is 95 percent of the equation.”

With so few residents in Chestnut to recoup the upfront costs of extending water lines, bringing water to the community isn’t economically reasonable, he argued.

“It’s not that I’m against it,” he said. “I look at it in a common sense-type way. I look at the numbers and the population of Chestnut.”

Residents like Thames interviewed by Inside Climate News said they understand the economic argument. But access to clean water for drinking and bathing should be a right, they said, not a matter of a financial cost-benefit analysis. Public officials have a moral obligation to extend the water supply to suffering rural residents, regardless of the financial calculus, they said.

Shelton told residents that if funding were actually secured, members of the Chestnut community could come back to Beatrice officials to discuss the matter. But for now, she said, there would be no commitment, written or otherwise, from the town.

“Right now, it cannot be done,” she said of supplying water to Chestnut.

Lasonja Kennedy, a resident of nearby Buena Vista who’s helped organize Chestnut residents, said the mayor’s stance puts citizens in a Catch-22. Without a formal commitment from a supplying water source, applying for grants to help cover the costs of running Beatrice’s water to Chestnut would be difficult, if not impossible.

“And water is a right,” Kennedy said after Monday’s meeting in Beatrice, a town of about 200 people. “These people need water one way or another.”

Hearing again and again from residents struggling to access water each day is heartbreaking, Kennedy said, and isn’t reflective of what claims to be the richest country in the world.

Earlier in the night, as the Beatrice meeting had begun, each Chestnut resident had stood and pledged allegiance to the American flag—that of a country as of yet unable or unwilling to provide them clean drinking water.

Yet those same residents, Kennedy explained, are burdened with unearned shame when they see someone they know in the grocery story, for example, and have pallets of water weighing down their shopping cart.

One resident described the feeling, Kennedy said, explaining that she would lie to her neighbor to explain all the water she’d purchased: “I’m just having a party.”

Kennedy said that among the hundred or so residents of Chestnut, nearly all face some type of water access issue. For some, that means frequent, often costly repairs to old water wells that have deteriorated year after year. For others, it means no access to running water at all, a result of a well that is no longer serviceable or a groundwater source that has simply dried up.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowEven when an aging well pumps water, it may not be suitable for drinking or cooking, she said.

Thames recalled the day nearly 10 years ago when his wife doubled over with stomach pain. The Thames family had to travel to a Mobile hospital more than 100 miles and a two-hour drive away to get medical care.

Medical professionals confirmed she had suffered from a parasite caused by contaminated water, Thames said. Since then, they’ve been taking the trips to Walmart at least once every week or so, buying enough clean water to survive in their Chestnut home, typically around 10 cases of 40 bottles—over 50 gallons in total.

He rarely invites family to his home, Thames said, because of the shame involved in not having access to clean running water.

“I get embarrassed that they can’t even take a proper bath or shower in the tub,” he said. “Everybody needs to wash.”

Jerry Johnson is one of the community’s few white residents. He said that the argument that there’s no money available for extending the water supply to Chestnut is unfounded.

“That’s bullshit,” he said. “There’s money available.”

Both Johnson and Thames pointed to other projects across the county that have recently been funded, projects like a splash pad for children and renovations at the county courthouse in nearby Monroeville, heart of Harper Lee country, widely considered to be the inspiration for her Alabama classic “To Kill A Mockingbird.”

“I just don’t understand why we can’t have running water,” Johnson said, frustration in his voice.

Asked about the danger of IRA or infrastructure money that could potentially help Chestnut disappearing under the new presidential administration, Johnson took out his phone and clicked the photos app. He turned his phone around and pushed it out from his chest with pride.

“Here’s my son with Trump,” Johnson said. “I’m not worried.”

The day of the Beatrice meeting, Trump had announced his plans to attempt a shutdown of USAID. Johnson brought it up, noting that Trump’s shuttering of the agency should free up billions in federal funding. In Johnson’s view, an application of an America-first approach would mean that money would now begin to flow to projects like providing Chestnut with public water.

“He’s going to do it,” Johnson said. “I know he will.”

He said he has a message for the president: “America first. American people first. Chestnut people are part of America, and they ought to have water.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,