Before the Palisades nuclear plant powered on in 1971, cancer death rates in Van Buren County, Michigan, were comfortably below the national average. But over the past two decades, rates in the area have risen to more than 13 percent above the national average, compared to 8 percent below it when Palisades began operating, according to a report analyzing Center for Disease Control data.

For those under age 35, the change in cancer deaths since Palisades opened was more drastic, soaring from 38 percent below the U.S. average to 50 percent above.

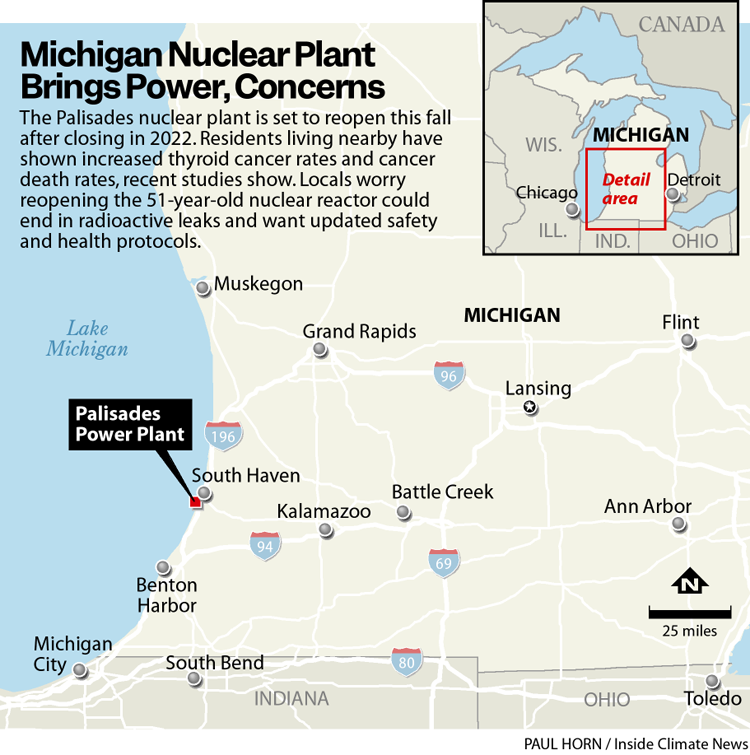

Palisades, one of the oldest nuclear power plants in the country, was scheduled to close in 2022. But after Holtec International bought the plant to decommission it, the company, which has never run a nuclear power plant before, decided instead to reopen it. The project was awarded a $1.5 billion loan from the federal Department of Energy to restart this fall and produce power until at least 2051.

A number of other nuclear plants across the United States are also slated to come back online to accommodate growing electricity demands, including Three Mile Island in Pennsylvania, the site of the most serious nuclear accident in U.S. history.

Michigan state officials have backed Palisades as key to meeting its clean energy goals, but residents say that reviving the plant comes with too many risks. Radioactive waste “is going to be here on the shores of Lake Michigan for the rest of our lives,” said Bruce Davis, a lifelong resident of Palisades Park and a member of the Michigan chapter of the Sierra Club. “And they want to start generating more.”

When Davis learned the plant would be reopening, he launched a survey on the health of his neighbors. The potential health impacts of exposure to radioactive material is a personal issue for Davis.

In 2003, his wife was diagnosed with thyroid cancer. Early the next year, her mother and sister were also diagnosed. The three live in different states, but all grew up spending each summer in Palisades Park, bordering the nuclear reactor.

Davis suspected exposure to radiation was to blame. The process of splitting atoms to produce nuclear energy has an unfortunate byproduct: radioactive material that must be isolated in secure storage containers for thousands of years. When ingested through food or water, radioactive chemicals can damage or kill cells in the thyroid gland, increasing the risk of thyroid disease or cancer.

Davis, along with epidemiologist Joseph Mangano, surveyed 702 full-and part-time residents living within 400 yards to one mile of the Palisades nuclear reactor. They found that residents living in Van Buren County were five times more likely to develop thyroid cancer compared to the lifetime potential of getting thyroid cancer in the rest of the nation.

“We anticipate that this gap will widen in the future, since some respondents will be diagnosed later in life; the average time from being exposed to ionizing radiation and thyroid cancer usually being 10 or more years,” the survey notes.

Van Buren not only exceeds other parts of the U.S., but also other counties in Michigan in terms of cancer death rates, according to data analyzed from the National Cancer Institute.

Davis and Mangano shared their reports with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the regulatory body in charge of approving Palisades’ reopening. “We were told ‘this is not in our purview,’” Davis said. In a pre-hearing last week, Davis and a group of homeowners petitioned the NRC to re-evaluate the safety of the power plant. The NRC insists that the plant is safe to continue operating.

“The NRC has been conducting inspections to verify that the plant’s safety systems, components, and programs meet the NRC’s requirements for the safe and secure operation of operating nuclear plants in the U.S.,” Viktoria Mitlyng, senior public affairs officer for the NRC, said in an email. “The NRC’s independent reviews are ongoing.”

But no level of exposure to radiation is safe, especially for children and infants, insists Mangano, who is also executive director for the Radiation and Public Health Project in New York. In similar studies of cancer mortality rates in communities living near nuclear plants, Mangano has found parallel trends: rates exceeded the national average and grew over the plants’ operating lifetimes.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowFor the Vogtle nuclear plant in Georgia, for example, Mangano analyzed CDC data and found that the local death rate from all cancers shifted from 7 percent below to 13 percent above the U.S. average after the startup of the plant’s Unit 1 in 1987 and Unit 2 in 1989.

Nuclear plants routinely release emissions through exhaust stacks and as liquid effluent into surface waters as a part of their normal operations. Releases are permitted by the NRC and utilities are required to monitor and report them. Gases and particles emitted into the environment, which contain radioactive materials, enter the body by breathing them in or by ingesting them via water and food, Mangano explained.

But Palisades also has had several instances of leaks in its history. In 2015, around 100 gallons of radioactive water leaked from a pipe on site. The plant shut down for five weeks in 2013 after it was discovered that about 90 gallons per day of “low radioactivity water” were leaking from a storage tank into Lake Michigan. The year prior, steam from a broken valve released between 5 and 50 gallons of water, forcing another shut down.

Holtec International affirmed that safety and health impacts are not a concern. “Palisades operated in the highest safety classification under the NRC regulations,” Patrick O’Brien, director of government affairs and communications at Holtec International, wrote in an email. “Safety remains our number one priority.”

The plant’s two-year outage has also allowed Holtec to improve the conditions of the facility, O’Brien said.

In a draft environmental assessment, Holtec and the NRC included their own evaluation of thyroid cancer rates in five counties surrounding Palisades from 2001-2020. Their data, which includes only full-time residents, did not find any significant differences compared to the state average.

“Emissions from Palisades are very low and a small fraction of the regulatory limits,” the assessment says. “Nuclear plant emissions are unlikely to contribute to cancer rates in the location population.”

Mangano emphasized that an analysis of just 20 years of thyroid cancer data isn’t sufficient. “The real question would be: What was the thyroid cancer rate earlier than that, and especially before Palisades operated?” he said. Thirty years into operation, those numbers could already include elevated cancer rates.

Until the full impact of Palisades’ operation on local health is understood, “No action to re-start the reactor should be taken,” Mangano said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,