PATAGONIA, Ariz.—“Look at the ground.”

Surrounding Rodrigo Sierra Corona in the foothills between the Santa Rita and Patagonia mountain ranges—two of Arizona’s famed Sky Islands that support isolated, high-elevation habitats—were dry creosote bushes and pod-less mesquites. He stood at the edge of a large pit in the ground that had formed where years of flooding had eroded the soil, leaving the roots of the mesquite trees exposed to the surface. The rainy season in this desert comes in just a couple of 25-minute storms during the summer monsoons, Sierra Corona explained. The rushing water forces its way along the path of least resistance through the dry soil, carving a visible path through the land over the years.

It’s a natural process, but one being made worse by climate change. Soils are dryer and temperatures are hotter. Overgrazing has wiped out much of the native vegetation, leaving barren land unable to effectively capture moisture. The rain comes less frequently and the region is undergoing aridification after years of drought. Together, the drier and more barren land exacerbates the erosion of the landscape, allowing sediment and water to run off and leaving behind scars in the earth like the one in front of Sierra Corona.

To restore the region’s hydrology, the Borderlands Restoration Network, a nonprofit conservation group at which Sierra Corona is the executive director, has installed thousands of erosion control structures. At the leading edge of a channel of erosion known as a headcut located on BRN’s wildlife preserve below Sierra Corona, the group had recently finished building zuni bowls—rock steps above plunge pools—and tiny dams to prevent the groove from spreading. The structures slow down the water, allowing sediment to settle and water to seep back into aquifers. Within the rocks of the zuni bowls are native vegetation seed balls coated in clay to keep local wildlife from eating them. When rain washes away the protective coating, the desert plants will sprout to restore the landscape as a whole as they grow and spread.

But BRN’s work to restore the degraded Sonoran Desert’s watersheds, native vegetation and steeply declining aquifers has largely paused, a victim of the Trump administration’s federal funding freeze and its targeting of conservation and climate work passed by Congress during former President Joe Biden’s tenure. Over $1.2 million of BRN’s funding is frozen, which accounts for 40 percent of its operating budget and includes three of its biggest, multiyear projects. BRN is just one of many organizations confronting funding freezes, with billions of dollars of money to address climate change in limbo across the country. Some states and organizations have filed suit to unfreeze the funds, but even when courts rule that the money must be released, the enforcement of those orders has been uneven.

As a nonprofit, BRN relies largely on donations, grants and federal contracts to pay for its work. Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act—President Biden’s signature climate laws that dedicated billions of dollars to addressing climate change and its impacts—BRN had secured and signed contracts with the U.S. Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management for restoration work across southern Arizona, and for rural youth internships. But under Trump’s Executive Order 14154: “Unleashing American Energy,” that funding is paused. Neither representatives of federal agencies nor the state’s senators in Congress have been able to tell Sierra Corona when or if the money will ever be unfrozen.

The White House did not respond to a request for comment. A statement from a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the Forest Service’s parent agency, said Secretary Brooke Rollins fully supports the president’s action.

“The Secretary has been reviewing USDA programs and funding from day one to ensure the American people’s hard-earned taxpayer dollars go to support the people and communities we serve, not the bureaucracy,” the spokesperson said. “Secretary Rollins is committed to ensuring USDA meets its many commitments to the farmers, ranchers, loggers, businesses, and especially rural communities, that rely on our services to grow and thrive.”

The funding freeze left positions BRN expected to fill vacant, and supplies like native seeds used for restoration work—which BRN staff harvest themselves—to sit idle. A paid internship program for youth in the region had to be canceled. All the while, BRN still has deliverables for multiple projects and deadlines before the summer heat kicks in—but no guarantee the cost of the work will be covered.

Sierra Corona hasn’t had to lay off staff, but if the situation remains the same by the end of the month, he will. The fate of twenty-five households vital to the small town’s economy now hang in the balance, out of his control, he said. At the end of 2024, they estimated they had enough funding to last until next spring, he said. But everything changed with the executive order.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“It sounds small,” he said. “But it’s less money in a place that needs resources.”

The news in the borderlands is often bad, he said, and BRN has tried to counter that narrative.

“Biologically speaking, it’s as rich as you can ask for a place to be,” he said. “It should be as relevant as talking about Yellowstone. But people who don’t know the place, when you say southern Arizona they think of a dusty patch with a skinny coyote and dying-out cactus, which is so far away from reality.”

The internships and education programs helped tell a more accurate story, by showing people the landscape, and by extension, the people in it, mattered.

“Everything we do ties back to the community,” Sierra Corona said. That includes helping ensure people’s taps keep running, helping ranchers keep their land healthy and educating the community about growing food in the desert and ecology in one of the world’s most biodiverse places. BRN is the town of Panatagonia’s second-largest employer, operating a 1,800-acre wildlife preserve, restoring local watersheds, operating an education center and running a native seed farm that replants habitats scorched by wildfires and sells crops to locals.

At the seed barn on a recent morning, local volunteers worked in the cold picking seeds off of plants collected from various elevations across the region, which Perin McNeli, BRN’s native plant program manager, said ensures biological diversity in the habitats they restore. If a wildfire burns through Chiricahua National Monument, they have seeds collected from the mountain that could be used to restore the area with the native vegetation that’s uniquely adapted to that specific environment.

BRN was formed in 2012, and McNeli said much of their work was just gaining momentum. They are in the process of building a new nursery with funding from the IRA, with the funding secured before Trump took office. Contracts were in place to provide seeds for restoration work to national forests in the area, but those seeds now sit in storage.

“It’s been so hard even to get the ball rolling with localized efforts to address climate change,” she said. Federal funding was finally changing that. It seemed steps were being taken in the right direction, she said, only for things to move “ten steps back.”

What’s scarier, she said, is that the urgency of the work grows with each day.

“The potential loss of not getting the seeds down is encroachment by invasives covering even greater land area than they already cover, and severe soil erosion and all the trickle-down effects from that,” she said. “The stakes are really high.”

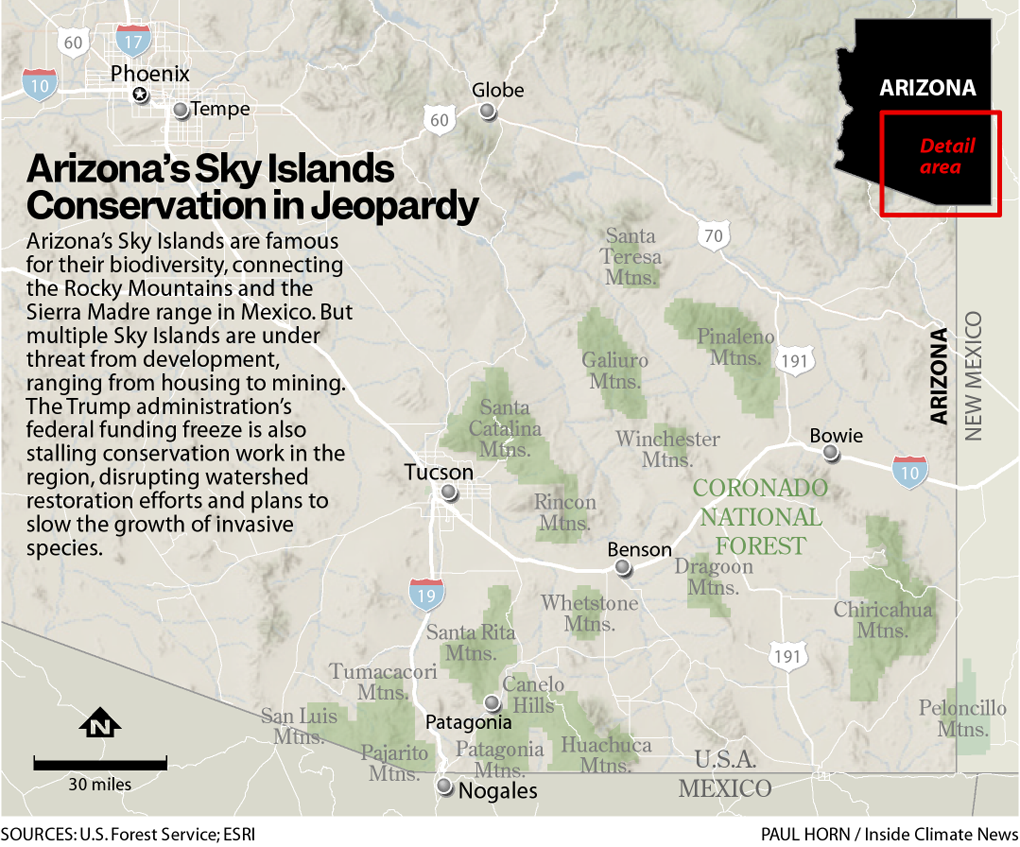

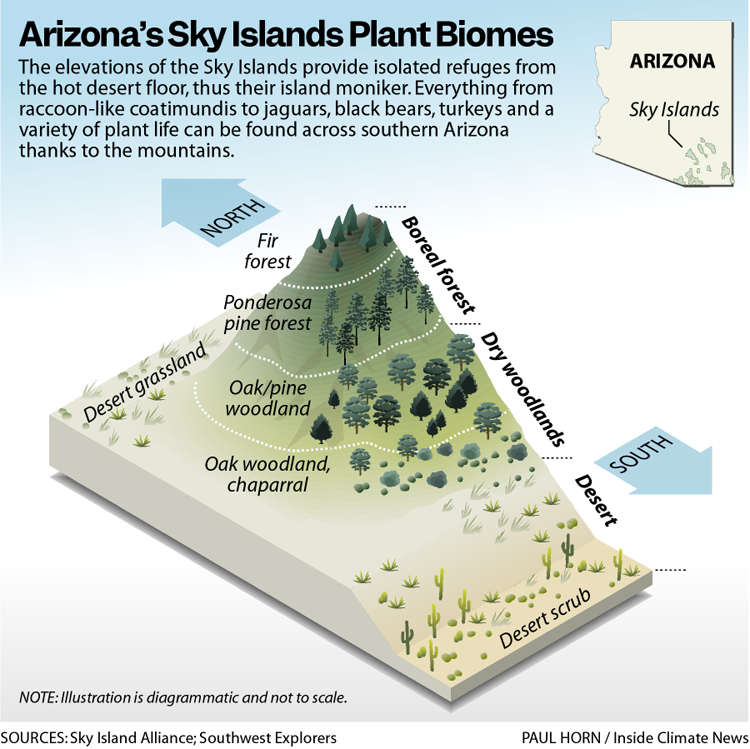

That impact is evident on the land. Southern Arizona and its Sky Islands are famous for their biodiversity, the elevations of the mountains providing isolated refuges from the hot desert floor, thus their island moniker. Everything from raccoon-like coatimundis to jaguars, black bears and turkeys can be found here in an area that serves as a bridge for wildlife, connecting the Rocky Mountains and the Sierra Madre range in Mexico.

Development, from major mines to housing, is changing the region. BRN’s preserve, which is open to the public, connects to two Coronado National Forest parcels, protecting a contiguous wildlife corridor. The difference between the vegetation of BRN’s land and its neighbors is obvious to drivers passing through. Slow down to spend some time there, and you’ll spot the rock formations that slow down the speed of water to allow the soil and aquifers to recover from all of the impacts on the land.

Overlooking one of the Zuni bowls in the foothills, Sierra Corona said eventually, the rock structure would be covered in sediment captured during the monsoon season.

“If you capture sediment, you will capture water,” he said, and then the vegetation will follow. “Forget about climate change—decide that you don’t believe in that—it’s fine, but you’re not changing the facts. And the fact is that we are running into a water crisis. If you look at the Southwest, the crisis is very real already, and it’s not going to get easier without drastic approaches to it. Our work is critical.”

His ask of the Trump administration is simple: Respect the contracts that have been signed.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,