ALTADENA, Calif.—After living here her whole life, Ayanna Blount has decided to leave this Los Angeles suburb for Lima, Peru.

Like many others, Ayanna’s family lost their home to the Eaton Fire in January 2025, which consumed much of the community, and a disproportionate amount of the Black enclave where they lived.

“I don’t see it happening for me,” she said. “It’s way too expensive and it was already expensive before the fire.”

Ayanna, 31, lived in a 4-bedroom house with her father, her spouse and two roommates. Her grandfather bought the house in the 1970s with money he earned working for the local gas company.

Ayanna’s favorite part of the house was a parlor that her grandfather added in the home right after he bought it. It was her refuge, complete with a bar, a fireplace and high wooden ceilings. Her love for the home spread out from that one room.

“It wasn’t perfectly done and it wasn’t really up to modern standards, but it was cozy and it added a little backyard,” she said. “Now, it’s gone.”

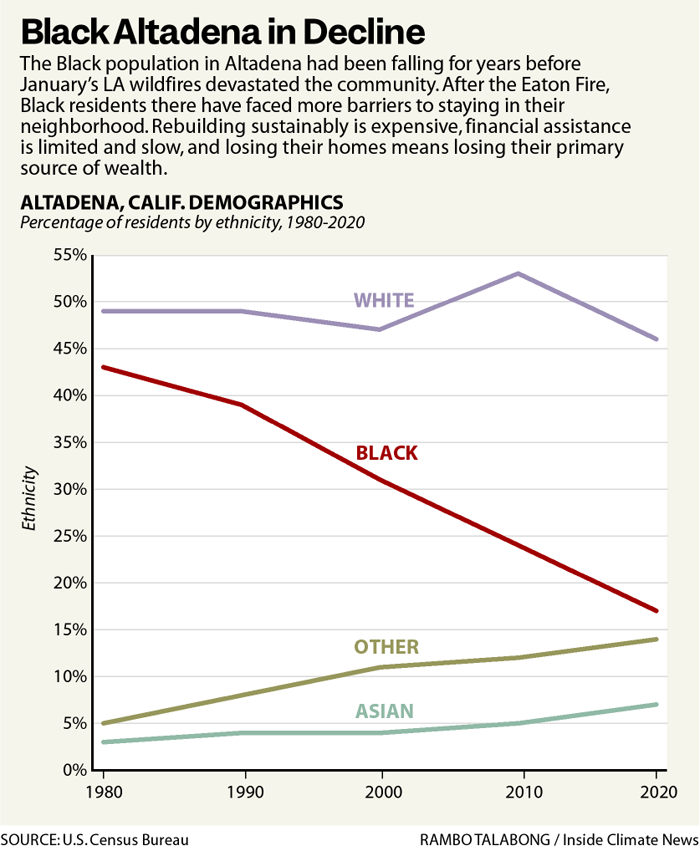

The Black community took root in Altadena during the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans moved to the North, Midwest and West to escape the racial violence of the Jim Crow South and seek better economic opportunities and safer living situations. The community of transplants from the South blossomed with the civil rights movement and, by the 1980s, four in 10 Altadenans were Black.

But today, only about two in 10 are African American, as rising prices and gentrification have driven some from the community. Altadena’s District Supervisor Kathryn Barger cited “speculative real estate practices, limited affordable housing and increased demand for properties in desirable neighborhoods” as main factors that have pushed the prices higher and driven gentrification. Los Angeles alone needs 500,000 more affordable homes, data from the nonprofit California Housing Partnership shows. And according to Altadena Heritage board member Val Zavala, even more people have been flocking to Altadena to purchase homes.

“Altadena used to be this hidden gem,” Zavala said. “It was cheap, had the feel of a small city, and it had a vibrant community. It has gorgeous views of the mountains. Word has gotten around about it and people who are looking for homes came here, willing to pay more than many of those who have lived here longer.”

House fires affect the eight in 10 Black residents of Altadena who own their homes worse than others in the community, as home ownership represented much of their wealth, said Heritage Board member and longtime realtor Claire Smith.

“The wealth is only there if you go to sell your home,” said Smith.

And the steep increases in the cost of living in the area have made it hard for many Altadena residents to hang onto their most valuable asset.

“It’s very expensive to be a homeowner in Southern California,” Smith said. “So when we talk about the decline among our more vulnerable neighbors, we’re seeing that as the cost of living gets higher and their incomes aren’t coming up to match it, that’s when homeowners are having a hard time paying their mortgage, paying their property tax and paying for the repairs.”

Ayanna is seeing all of this play out among her friends.

“There’s a lot of people who are already feeling like they have to sell their homes, where that was their little piece of generational wealth, and they can’t afford to rebuild it,” she said.

Barger’s office estimated that the Eaton Fire destroyed around 6,892 residences in Altadena. While the county has no “granular information” about the demographics of those who lost their homes, the Bunche Center at University of California Los Angeles estimated that Black residents were more likely to have suffered losses from the fire. The center’s research estimates six in 10 Black households stood inside the perimeter of the Eaton Fire in Altadena, as compared to only five in 10 for non-Black households. Racial segregation pushed Black residents to more at-risk areas, according to the center’s researchers.

The Bunche Center also found that Black Altadenans were more burdened by the cost of housing, spending at least a third of their income on a place to live. About seven in 10 of them are cost-burdened, compared to just three in 10 of their non-Black residents of the community.

In 2013, Ayanna dropped out of college to work as an electrician and then as a barista at Starbucks. Paying just $750 a month in rent to her father, she was able to stay in the neighborhood with blue-collar and service-sector jobs.

That’s not an option anymore.

“I don’t have a degree, but I do have tens of thousands of dollars in debt,” Ayanna said, referring to the student loans she still needs to repay after dropping out. “As far as how much money I was able to save as a cushion, I have a few thousand dollars. So my net worth is still in the negative.”

Although Ayanna decided to leave the country after the fires, the rest of the Blounts decided to keep their property and rebuild their home. They estimate that rebuilding will cost at least a million dollars, even with family members doing the construction themselves.

“It’s going to be expensive, but we have to do what we can to stay,” said Nick Blount, Ayanna’s father.

For architect Winston Thorne, a member of the National Organization of Minority Architects and the Altadena Rebuild Coalition that formed after the fire, residents like the Blounts will face a reality check.

“Managing expectations comes in, which means having a real look at what are the financial implications of this process and then determining, based on that, whether or not there are achievable goals,” Thorne said. “If not, then what are the alternatives?”

He adds that Altadena families taking on their construction projects would have to be careful to comply with all the building, zoning and fire safety codes that have been updated since their original homes were built.

“It doesn’t absolve them from having to abide by the authorities having jurisdiction,” he says.

The Blounts hope to fund their rebuild by getting the most out of their homeowner’s insurance and help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but they have not made much progress with getting money from either.

Nick said it’s his fault for being “underinsured” and for not being able to work on the FEMA documents sooner.

“I don’t blame the insurer or FEMA. With FEMA, I was caught up with cleaning up our lot so I wasn’t able to submit the documents at the start. With insurance, there were other things that I prioritized for spending over the years. I didn’t think that the fire was going to reach us,” Nick said.

Most of what they have brought in to cover their living expenses, replace the burned cars they use for work and start the rebuilding process is from their GoFundMe campaign.

California Department of Insurance Deputy Commissioner Michael Soller said the department can help underinsured residents negotiate with insurers to restore coverage or dispute the cancellation of policies for unpaid premiums, but individuals must first contact the department.

“Disputes often arise when people get estimates from contractors and insurers refuse to pay or coverage falls short,” Soller said. “That’s where we step in and push insurers to do more.”

Ayanna and Nick estimate it will take at least 3 years of work for the family to rebuild, enough time for her to pursue a degree in environmental studies in another country. She plans to return to Altadena from time to time to help her father.

“I love my community. I might have to be away from them and it’s going to hurt,” she said. “I was crying, but I told myself, ‘I just need to appreciate it for how it is right now and know that even if things change, it is not gone forever.’”

Waiting on FEMA

Arlynn Page’s rented house still stands thanks to her son, Elijah. They’d moved there in November 2024, relishing how Arlynn, 61, had found their “dream home.” It had three bedrooms, a spacious front yard and a view of the canyons in the San Gabriel Valley.

They treasured the home so much that, after evacuating, Elijah, 25, rushed back to the neighborhood to fight the fires himself.

“My son called me and said, ‘Mom, how can I get on the roof?’” Arlynn recalled.

Her son described a scene of horror—neighboring houses ablaze and the fire creeping closer. With a bucket, he drenched what he could, determined to hold back the inferno. By sunrise, the next-door neighbor’s home was a bed of ashes but the house where Elijah and Arlynn lived stood untouched by the flames.

Still, Arlynn and Elijah have not spent a night back home since the fires in January. They have moved between nine Airbnb and hotel rooms across Los Angeles and have no idea when they’ll be able to move back to her rental.

Unlike those whose homes were reduced to rubble, Arlynn is caught in a different kind of purgatory. The fire released pollutants from old homes, some laced with asbestos and lead paint, as well as from plastics, vehicles and other materials that can release toxic fumes when they burn. Their landlord stopped them from returning the house that has become unlivable due to toxic smoke damage. Arlynn lost her mattresses, her curtains and much of her clothing to the smoke, something she was not prepared for.

“If it were just a wildfire, it would be different,” she explained. “But because homes and cars burned, there are carcinogenic pollutants in the air. It’s like what happened with the firefighters at 9/11.”

The owner of Arlynn’s home had not insured it. Arlynn had planned to get renter’s insurance in February, but the blazes came in early January, an unusual time of year for wildfires in southern California.

“It cost me almost $20,000 to move, and my plan was to get insurance after settling in,” she said. “So now, I have nothing.”

With California’s insurance market caving in from about $20 billion in losses from the January fires, policies that many residents already couldn’t afford are expected to grow even more expensive and inaccessible.

In response to this, the Department of Insurance is pushing for the Sustainable Insurance Strategy, a plan that aims to stabilize the market by expanding coverage in high-risk areas while allowing insurers to use catastrophe modeling—computer simulations estimating disaster risks and potential losses—to set rates. The strategy is designed to shift people out of the embattled California FAIR Plan, which Soller at the California Department of Insurance described as having “higher cost” but “limited coverage.”

The fundamental idea, he explained, is that greater availability leads to greater affordability. “Insurance companies are increasing their rates legally, but they’re not writing more policies,” Soller said. “That’s the problem.”

Nicole Mahrt-Ganley, associate vice president of public affairs at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA), said that insurers continue to be “committed” to Californians, but she argued that market conditions have become “out of balance” for years.

She pointed to several factors that have driven up costs for insurers: Disasters are getting more expensive, inflation has driven up rebuilding costs and regulatory delays have insurers struggling to get rate increases approved in time to keep up with the rising risks.

The industry supports California’s Sustainable Insurance Strategy, Mahrt-Ganley said, but she emphasized that insurers must be able to charge “adequate rates to cover losses” to remain in the market.

Ultimately, the rates determined by their models will become available to people like Arlynn, but she couldn’t access them in time to help her recover from the smoke damage from the wildfires.

Arlynn applied for aid through FEMA and was approved. But nearly two months later, she has not received a deposit.

“We were told the funds would be available by Friday,” she said in early February. “That was four Fridays ago.”

Verification requirements delayed the Pages’ aid, Arlynn said. Elijah met with FEMA after the fire as Arlynn scrambled to deal with the smoke damage and her landlord. When FEMA asked for Elijah’s social security card, they found out he did not have one.

“So we had to get him that first before we could move forward,” Arlynn said.

According to a Harvard study, Black Americans often receive less Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) relief funding on average and take longer to recover compared to their white counterparts.

In a statement to ICN, FEMA said there are “several factors” that may cause delay in disbursing of funds, including complications in processing the payouts through banks, dealing with appeals and verifying the identity and eligibility of claimants—what Arlynn and Elijah experienced.

“To ensure proper use of taxpayer dollars, FEMA must verify an applicant’s identity, home ownership or occupancy, and disaster-related damage,” an agency spokesperson wrote in an email response to a request for comment. “This process may require additional documentation from the applicant.”

Arlynn’s landlord has since deep-cleaned and vacuumed the house and installed air purifiers inside. But even if her home is eventually cleaned of toxins left by the smoke, it won’t be enough for a homecoming, as remediation is a slow, communal process. The ashes of the houses that burned around the Page’s home could recontaminate everything when they are stirred up. So the people whose homes survived will have to wait to move back in for those whose burned to finish cleaning up their properties.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowArlynn and Elijah’s landlord has urged them to move back so he can collect rent again, but Arlynn doesn’t feel safe and has declined. She learned about her right to refuse to return from the victim awareness group PostFire. “They recommend being at least 750 feet away from any burn site,” Arlynn said. The original advisory from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health warned residents to maintain that distance from burnt structures to avoid “long-term health impacts.”

“I don’t know how long that will take,” Arlynn said.

Trapped in this wait, she has started to rethink whether to keep fighting for the home of her dreams or to move on.

“That’s the part that makes me want to cry,” Arlynn said. “Am I holding on to a dream that I have to let go of?”

Insurance for a Community

Emeka Chukwurah stood with his father in front of a pile of rubble, surveying the ruins of their store, Rhythms of the Village, the morning of January 8. For 12 years, it was a place where the past met the present—where Nigerian textiles hung, where the rhythms of West African drums echoed between walls covered in works by Black artists and where neighbors stopped by just to talk.

Emeka wants it all back. He wants the community to return to the Village. But two months after the fire, the obstacles are piling up.

His business insurance coverage was supposed to help, but the payout he’s being offered—$150,000—is a fraction of what he lost. “That’s not enough to replace even the inventory,” he said.

By his estimate, he lost close to $900,000 in goods, equipment and cultural artifacts, which he listed and sent to his insurer. And that’s before considering the cost of setting up in a new space, since the building he rented was also destroyed. Many of these lost items held cultural significance for the African-American community in Altadena, with Emeka describing them as “one-of-one” pieces, which made it hard for him to assign a dollar value on them.

“I bought museum-like pieces that I purchased for the store that were priceless to me,” Emeka explained. “Certain things I got for my birthday, splurging because I wanted something special for people to see in the shop—not necessarily even to sell, but to share our authentic culture through these artifacts.”

Among the losses he most treasured was a framed photograph of his father’s original band with Fela Kuti, the legendary father of Afrobeat. His father, Onochie Chukwurah, played bass in this band when Kuti came to the U.S. in 1969.

The fire also destroyed numerous pieces of paper mâché and canvas art.

“These were pieces of my father, part of a collection I hoped to pass down to my son,” Emeka said.

Insurance companies typically require detailed inventories known as a “proof of loss” to prove claims and prevent fraud. However, reconstructing a complete list from memory is especially difficult when items have intangible cultural and emotional value, which often results in undervalued claims.

Organizations have advocated for reforms to ease this burden. According to Annie Barbour of United Policyholders, the advocacy of her group and others for reforms to ease this burden prompted Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara to introduce rules encouraging insurers to offer payouts of up to 75 percent of contents coverage without exhaustive inventories, an effort to make the claims process more compassionate and efficient for disaster survivors.

For residents who have lost “unique” or “sentimental” items, Barbour advised that they look for items of the same characteristics online—on Ebay or Craigslist, for example—to prove their value. In the case of Rhythms of the Village, they can look at the prices of African artworks and instruments.

“In a perfect world, you would’ve taken that pre-fire, sent it to your insurance company, and say ‘This is the professional appraisal that’s been done on them,’” Barbour said. “But people don’t think that far in advance.”.

Emeka has lawyers reviewing his policy, pushing for a larger settlement, but until his payout is resolved, the Village will stay in limbo.

The insurer of Rhythms of the Village did not reply to a request for comment.

Still, Emeka is trying to keep the dream alive and stay in Altadena. He envisions a space that is more than just a store, and dreams of also hosting a Black history museum, an artists’ collective—things that ensure that what was lost in the fire isn’t lost for good.

“We are a pillar in the community,” he said. “It’s the Village. It’s what it means to be communal—for us to live together as one. I believe that’s what we’re in the business of doing. It’s bringing people together.”

While Emeka waits for the resolution of his insurance situation, Rhythms of the Village has a temporary home at his father’s house in residential Pasadena, where a relief center has sprung up in the garage and backyard with racks of clothes and piles of furniture for anyone who needs them to take.

In the living room, Emeka sets up instruments, microphones and speakers for the first rehearsal of the Village’s music group since the fire. There is tuning and laughter.

Ayanna Blount and Arlynn Page huddle in the circle, ready to sing.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,