The Rangeley Lakes region can often feel like a forgotten corner of Maine, far from the state’s famed coasts or cities. This western stretch is remote, rugged woodland. Forests become impassable in spring’s muddy months and cool mountain streams teem with a trout population that draws legions of recreational fishers. It’s also a part of the state where logging and timber hauls have indelibly shaped the land and livelihoods of those who live there.

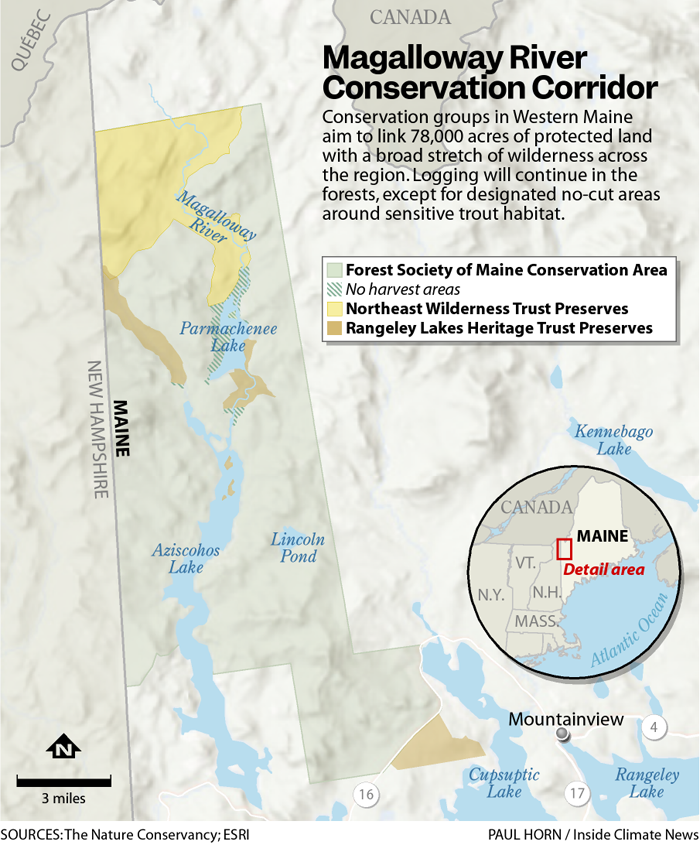

Now about 78,000 acres surrounding the Rangeley Lakes may soon be linked to 500,000 acres of protected land reaching across central Maine to New Hampshire. A project announced March 18 and agreed to by four leading conservation groups and a 70-year-old timber company aims to bolster a priority spawning ground for brook trout, broaden a migration corridor for wildlife and restrict future development in the woodlands.

The plan to permanently protect lands around Maine’s Magalloway River is the brainchild of the Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust, the Forest Society of Maine, the Northeast Wilderness Trust, and The Nature Conservancy.

The conservation groups and Wagner Forest Management, a timber company that manages the property on behalf of its owner, Bayroot LLC, have been discussing the project since 2023. Logging will continue on the majority of the protected land, about 62,000 acres, with no-cut areas established around critical brook trout habitat. The Forest Society of Maine will hold a conservation easement on the land owned by Bayroot as part of the agreement, which is contingent on funding.

The conservation groups plan to raise $62 million, largely from private donors, by May 2026. The Rangeley Lakes Heritage and the Northeast Wilderness trusts will buy smaller parcels within the protected area as part of the deal.

“This is a project that is significant at the scale of the entire Appalachian corridor. It’s a really key gap in the Appalachian landscape in terms of lands that are conserved,” said Mark Berry, forest conservation manager for The Nature Conservancy in Maine.

Bringing Back River Curves

Wagner President Dan Hudnut said conservation groups have been interested in these lands since Bayroot purchased them in 2003, and the company saw an opportunity to protect its investment as well as wildlife.

Keeping the land forested was key, Hudnut wrote in an email: “We are great believers in the value of working forests, which support the regional forest economy and rural communities, as well as water quality, wildlife habitat diversity, recreational opportunities, and climate benefits.”

As part of the easement requirement, the logging company has agreed to incorporate conservation measures into its land management plan, which the company will review annually with the Forest Society of Maine.

Wagner has also agreed to leave 100-foot no-cut buffers around particular trout habitats. The untouched terrain will help to shade the river system and provide woody leafy material that adds structure and nutrients for wildlife.

Much of Rangeley Lake Heritage Trust’s work around the Magalloway attempts to undo some logging industry changes over the years, from the heyday of sending logs down rivers and modern times of trucking timber from the forest.

“[Historically,] log drives would bulldoze the rivers and straighten the rivers,” said Patrick Sullivan, development director for the organization. “Then, when they moved from log driving to current logging operations with trucks, they needed to put in extensive road networks. A lot of those road networks created barriers through culverts.” Those river crossings can easily become breached, and instead of flowing under a road through a water-filled culvert, the fish are stuck on one end of an impassible, dry tunnel.

Like Atlantic salmon, some brook trout spend their adult lives at sea before running up rivers to spawn in streams and gravelly, sandy, shallow waters.

Even trout that spend their entire lives in freshwater need connected rivers, conservationists said. “Brook trout need to move,” said Lauren Pickford, the Maine project manager for Trout Unlimited, a conservation group not associated with the project. Some brook trout may swim up to 50 miles in a season to reach their spawning grounds in cool pockets of rocky river bottom, she said. The fish, throughout their lives, lay eggs at the same site where they themselves hatched.

“If there’s a barrier in between, they’ll keep trying to get through that barrier until the conditions are right to get through it, or they’ll just wear themselves out,” Pickford said.

A major step of the restoration along the Magalloway is to replace culverts with open-bottom bridges, similar to what the Rangeley Lakes Heritage Trust did in the nearby Kennebago River watershed in Maine.

Another planned improvement is what Sullivan called “chop and drops,” a strategy of leaving some harvested timber in streams to restore a river’s natural meandering and reverse some effects of commercial logging.

Decades ago, before timber was trucked from the forest, loggers straightened winding rivers to send harvested logs downstream. It was an easier and speedy way to move timber. But over time, the fast-moving waters formed the river bed into a V-shape that eroded silt and soil.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowChop and drops are meant to slow the river’s current, allowing more sediment to build for a prime spawning habitat. Reintroducing natural variability in the river’s current creates “pools and riffles,” Pickford said, referring to deep and shallow spots in the river bed. These are crucial for wildlife health. “Riffles have gravel in them which the trout like to spawn in, and then the pools are a good place to rest and hide.”

Log drops also add leaf litter and bark to the water, which is like a buffet for bugs and macroinvertebrates. Those creepy crawlies become an all-you-can-eat feast for trout, which benefit from the insects’ greater nutrient content, Pickford said.

A Cold Stronghold

The structure of the river and healthy food sources are just two components of what trout need to thrive. They must have cold and oxygen-rich water. The Magalloway has that in abundance.

Despite the footprint of logging, cold mountain streams have made the Magalloway among the country’s most important trout habitats.

Trout Unlimited, a nonprofit with more than 370 chapters across the United States, surveys watersheds across the country and found that Maine has more priority trout habitat than anywhere else. The Magalloway is one of Trout Unlimited’s national priority watersheds and a place where the species can thrive, given climate shifts.

The conservation groups behind the Magalloway project aim for the entire region to become a haven for all kinds of land-dwelling wildlife seeking cooler climates. Among their concerns: Canada lynx, black bear, moose and a range of the region’s birds.

“There’s a lot of conservation synergy,” said Berry of The Nature Conservancy. “The things that this project enables (which) benefit brook trout—like protecting riparian buffers, allowing the growth of old forest and riparian corridors, making sure that the streams are functioning and unimpaired by road crossing—are good for all sorts of other species. Riparian corridors make great movement corridors for lots of wildlife.”

Connecting Conservation Corridors

Meade Krosby, a senior scientist at the University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group, has studied climate corridors, connected wildlands that allow for broader migration as the climate changes. “Species have been doing this for millions of years. They just have to do it much faster right now because the pace of climate change is so fast, and there’s now lots and lots of stuff in their way like cities and agricultural areas,” Krosby said.

Rivers like the Magalloway are perfect foundations for such corridors, she said. Most rivers run from high to low elevation, tracking climatic gradients, and the cooling effect of the water and surrounding vegetation “tends to have a buffering effect” on temperature swings.

Protecting these areas now is crucial for species-wide survival, especially for animals with a “really narrow climatic niche,” Krosby said. She described the changes that wildlife face—in temperature and habitat—as a matter of a “range shift” of tolerance.

“It’s not like the range shift is each individual salamander with a little suitcase,” she said. “The range shift is happening at the edge of the species’ range, where those (migrating) individuals are at the leading edge. They’re facilitating that shift by leading into new areas. At the trailing edge, where it’s no longer suitable for them, those individuals, many of them, will ultimately not be able to reproduce, or there will be higher mortality.”

Berry sees this 78,000 acres at Rangeley Lakes as filling such a “key gap” in conservation land across New England. “This is one of those places that has some forest management gravel roads but is mostly still forested habitat and natural wetlands and rivers, streams and lakes. Species can move through that kind of landscape relatively freely,” Berry said.

The conservation effort in Maine is underway as environmental protections and the timber market face uncertainties. President Donald Trump has issued a flurry of tariffs against other trading partners and nations as well as an executive order to increase timber harvests on federal land.

The conservation groups behind the Magalloway project said they anticipate private donations will cover most of the costs. They applied for a grant through the North American Wetlands Conservation Act and have calculated that those federal funds would cover 10 percent of the total cost.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,