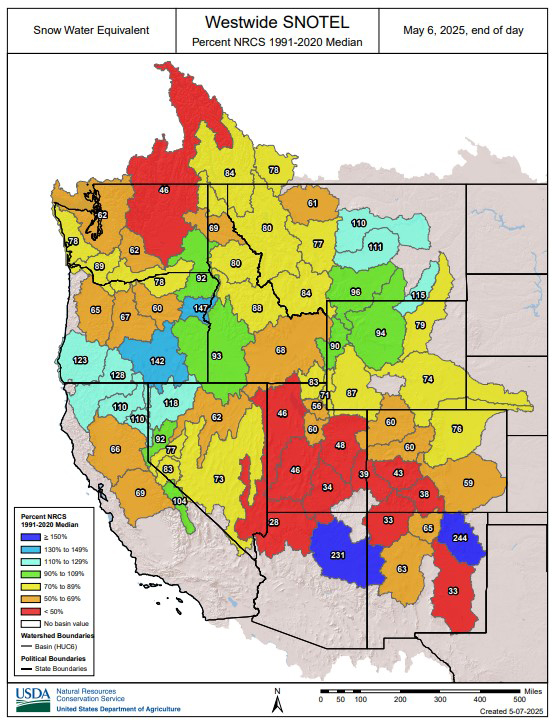

If you took a look at a map of Rocky Mountain snow right now you would see a lot of red.

The mountains that feed the Colorado River with snowmelt are strikingly dry, with many ranges holding less than 50 percent of their average snow for this time of year. The low totals could spell trouble for the nation’s largest reservoirs, but those dry conditions don’t seem to be ringing alarm bells for Colorado River policymakers.

Inflows to Lake Powell, the nation’s second largest reservoir, are expected to be 55 percent of average this year, according to federal data released this week. If forecasts hold true, 2025 would see the third-lowest amount of water added to Lake Powell in the past decade.

“It’s looking like a pretty poor water supply and spring runoff season,” said Cody Moser, a hydrologist with the Colorado River Basin Forecast Center.

If Lake Powell drops too low, the reservoir would lose the ability to generate hydropower for about five million people across seven states. Much lower, and it could lose the ability to pass enough water downstream, where tens of millions of people depend on it.

Eric Balken, who watches Lake Powell closely as director of the nonprofit Glen Canyon Institute, said this year’s snow data is concerning, but it isn’t driving the same level of concern from policymakers and media outlets that emerged in previous dry years.

Balken said that may be happening for two reasons.

First, it’s because negative outcomes might not be felt immediately. Lake Powell is unlikely to drop low enough to lose hydropower capabilities this summer, but the dry spring is making that more likely to happen in 2026.

Second, it’s because water managers simply have bigger fish to fry.

The federal offices that manage Western water are in disarray amid layoffs and restructuring since Donald Trump returned to the White House. The Bureau of Reclamation, the top federal agency for Colorado River dams and reservoirs, is without a permanent commissioner.

All the while, state and federal policymakers are spending most of their time and attention on drawing up new water-sharing rules. The current rules expire in 2026. Talks between states have reached a standstill, and negotiators say they’re working toward a compromise.

“That chaos within the agencies, the broader negotiations happening on the Colorado River, all of these other factors, I think, are sort of drowning out the severity of the drought situation right now,” said Balken.

This year got off to a strong start for mountain snow, but took a dip during a dry spell that lasted from December through February. Snowmelt from Colorado accounts for about two-thirds of the water in Lake Powell. A portion of Western Colorado saw less than 15 percent of normal precipitation from December through April.

Scientists say these low snow years are the result of climate change, which is causing less snow to fall, and more of it to be soaked up by dry, thirsty soil before it has a chance to reach rivers and reservoirs. That has left the Colorado River in a dry trend going back more than two decades.

Balken said the climate reality is here to stay, and should spur the region’s leaders to rein in demand accordingly.

“Just because we’ve gotten used to it doesn’t mean that it’s not a problem,” he said. “We have to stay laser focused on what’s happening on the Colorado River, because there are some very big problems that need to be addressed.”

This story is part of ongoing coverage of the Colorado River, produced by KUNC and supported by the Walton Family Foundation. KUNC is solely responsible for its editorial coverage.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,