Scientists have long known that changes in temperature can affect the risks and spread of infectious diseases by altering the biology and behavior of pathogens and their hosts, from butterflies to people. And evidence that climate change can exacerbate more than half of known human pathogenic diseases has underscored the urgency of understanding how extreme heat shapes disease outcomes.

Now, new research from scientists at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland suggests that heat waves can dramatically alter a parasite’s numbers and ability to cause disease in unpredictable ways.

Temperature fluctuations have complex effects on hosts, parasites and their interactions. For example, elevated ocean temperatures can reduce the ability of corals to fight infection while increasing the virulence of their pathogens. But heat can also harm hosts in a way that impedes parasite growth, as recent research in monarch butterflies suggests.

“We didn’t really know what we were expecting going in,” said Niamh McCartan, a Ph.D. candidate at Trinity College Dublin, who led the research. “That’s why I did 64 heat waves,” she said, referring to the number of experimental treatments.

McCarten knew from her own and others’ research that extreme cold and heat have different effects on a parasite’s fitness—in this case, measured by the number of parasite spore clusters and their ability to infect their host. That led her to suspect that heat waves could have variable effects on parasites and thus disease spread.

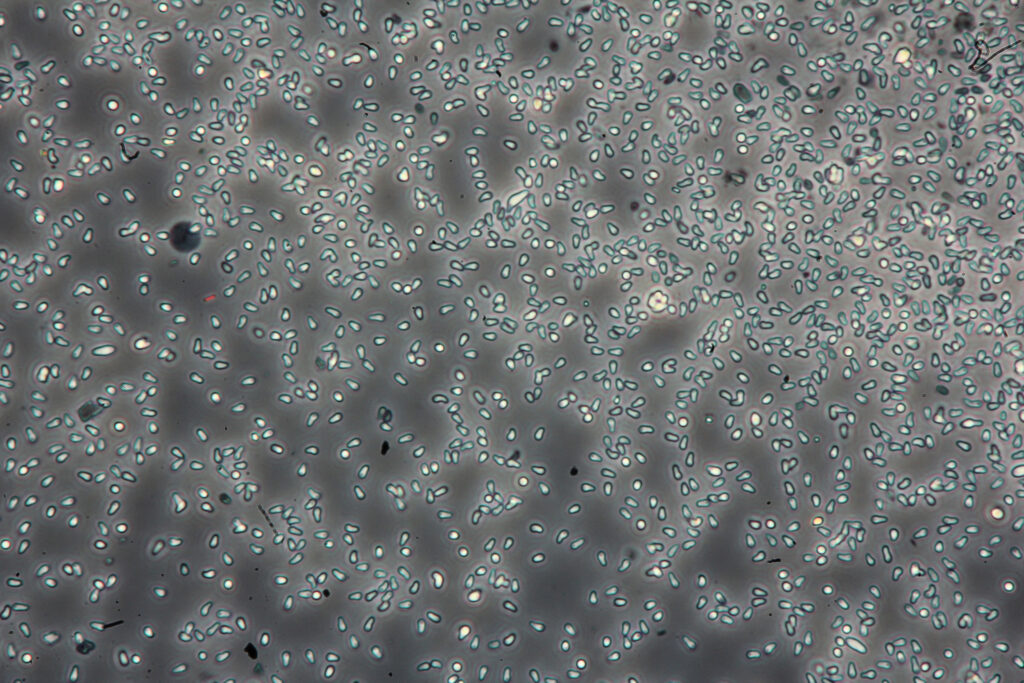

In the new study, published in PLOS Climate, she simulated the effects of heat waves on disease dynamics using water fleas (Daphnia magna), invertebrates at the base of freshwater food webs, and their parasite (Ordospora colligata), which forms spore clusters when it invades the fleas’ guts. This pair is a go-to experimental model for studying how environmental shifts like climate change affect interactions between pathogens and their hosts.

To understand how different aspects of high heat can modify the consequences of host-parasite interactions, McCartan and her colleagues infected water fleas with their parasites’ spores and altered the timing (before, during or after infection), magnitude (3 or 6 degrees Celsius above baseline temperature) and duration (short or long) of heat wave treatments across four baseline temperatures meant to reflect real-life conditions.

They chose two temperatures to simulate heat waves based on what the water fleas might see in their natural environment, McCartan explained, not knowing what to expect.

They verified the reproducibility of the setup by tweaking a few variables and using a single baseline temperature in a second set of experiments, and dissected the water fleas to determine the parasites’ prevalence (by noting presence or absence of infection) and burden (by counting the number of spore clusters).

The team found that all the factors influenced the prevalence and proliferation of parasites, with the outcomes depending on the baseline temperature. “Not all heat waves are the same,” McCartan said.

How much potential damage the pathogen can do depends on what the temperature is when the heat wave hits, when it hits in relation to infection as well as how strong the heat wave is and how long it lasts, the findings show.

“And all these factors interact in different ways, to show that even the same heat wave that happens before you get infected might not have the same results as if it happened after you got infected,” McCartan said.

McCartan found that exposing fleas and their parasites to heat spikes delivered at lower baseline temperatures gave the parasites an advantage, increasing their numbers by nearly 2.5 times. But exposing the hosts and parasites to the most intense heat wave treatments, which started at the highest baseline temperature, resulted in a 13.5-fold decrease in parasite numbers.

“It’s a great article and I think it does have broader implications,” said Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, co-director of the Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development and a professor of pediatrics and molecular virology and microbiology.

As the COVID pandemic took off, Hotez and his colleagues at Texas Children’s Hospital developed and licensed low-cost, patent-free COVID vaccine technology to vaccine producers for use in poorer countries, allowing more than 100 million people to receive a shot at minimal cost.

The Trump administration’s attacks on science and federal funding of research include cutting more than $500 million in infectious disease research and removing studies from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including one that reported substantially higher rates of hospitalization and death among unvaccinated versus vaccinated individuals.

The shots were deployed just in time. Recent research found that heat waves accelerate the spread of infectious diseases in people. Roughly 70 percent of global COVID-19 cases could have been avoided if there had been no heat waves in the summer of 2022, researchers reported in the journal Environmental Research.

Vaccinated individuals can still contract the virus but typically have much milder cases. Without the vaccine, there would have been much higher hospitalization and death rates.

The vast majority of deaths after vaccines became available were among the unvaccinated, Hotez said.

Death rates in the United States were 20 times higher among those who did not get vaccinated in 2022, during the first three months of the omicron wave, compared to people who were vaccinated and had a booster.

Playing Out in Real Time

The new study points to the inherent complexity of understanding and predicting how heat waves might impact the roughly 1,400 pathogens that infect humans, let alone those that affect wildlife and critical food crops.

McCartan found that even small temperature jumps can change how the host and parasite interact. The outcomes are “quite context specific” and “can be quite complicated” when trying to make generalizations and plan for what will happen in the real world, she said.

Yet findings also have real-world implications for Daphnia, which is not just a powerhouse model organism in the lab but also a critical food source in freshwater ecosystems across the Northern Hemisphere.

And extreme temperature fluctuations and heat waves triggered by global warming are already affecting the timing, location and course of infectious disease outbreaks.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe dynamics explored in the paper are playing out in real time, said Hotez, a leading authority on so-called neglected tropical diseases like Zika and dengue, viruses transmitted by mosquitoes. “In Texas and in the Gulf Coast of the U.S., we’re seeing a rise in vector-borne disease, and it’s pretty sharp.”

Hotez, who was fascinated with Daphnia as a child and decided to go into parasitology when he realized the fleas had parasites, said experts are seeing serious infectious diseases rapidly expanding beyond their normal range.

“You’re seeing now yellow fever expand out of the Amazon into southeastern Brazil, you’re seeing big upticks in dengue and Zika and chikungunya,” he said. “And I think what happens in Brazil eventually winds up in the Caribbean, in Texas and the Gulf Coast.”

The expansion of infectious diseases appears to be most apparent in invertebrate vectors and their pathogens, Hotez said. “That’s where we’re going to see the effects of climate change, first and foremost.”

That’s why he’s been sounding the alarm about the need to create a “climate health warning system” to monitor for diseases in Texas and the Gulf Coast and head off an outbreak.

“We’re taking two hits. They’re backing off on climate science funding and they’re selectively targeting infectious disease funding and pandemic preparedness.”

— Peter Hotez, National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine

Yet, as infectious diseases are expanding, the Trump administration has fired federal scientists and slashed funding needed to manage and prevent disease outbreaks. As Sen. Bernie Sanders reported last month, the administration is cutting more than half a billion dollars from the infectious disease budget of the National Institutes of Health, the world’s largest funder of medical research.

“The profound loss of the critical expertise at the Department of Health and Human Services, our nation’s highest office responsible for the health of the American public, will make our country significantly less safe from both chronic and infectious diseases,” the Infectious Diseases Society of America said in a statement after mass layoffs to the NIH and other HHS agencies were announced in April.

“We’re taking two hits,” Hotez said. “They’re backing off on climate science funding and they’re selectively targeting infectious disease funding and pandemic preparedness.”

Hotez believes Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is selectively targeting infectious disease funding and pandemic preparedness because of his “germ theory denialism” and dismissal of COVID’s risks.

The HHS press office did not immediately respond to a request for comment about that and experts’ warnings that massive cuts to infectious disease research will endanger public health. When news of the budget cuts first emerged in April, an HHS spokesperson told The Washington Post that “no final decisions have been made” on the budget.

But Hotez has other sources of funding. He and his team recently received a $500,000grant from a private philanthropic organization to help fund the Texas Virosphere Project. The project aims to reduce climate-fueled health risks by sequencing the genomes of key vectors and their viral pathogens.

So far, McCartan isn’t personally affected by the chaos the Trump administration’s science funding cuts has created in the research world. But even in Ireland, she can see the cuts affecting scientists around her.

Still, she hopes her research inspires scientists working on diseases in other invertebrates like bees and butterflies to consider studying how temperature fluctuations affect disease. That focus will be increasingly important as heat waves become more common in places like the Gulf Coast and parts of southern and central Europe, McCartan said, allowing vectors like mosquitoes to thrive with their pathogens in regions that were once too cool for them.

The researchers’ most extreme heat wave treatments pushed Ordospora to its thermal tolerance limits without harming the fleas. But both parasites and hosts’ ability to tolerate heat varies across species under different conditions. Some parasites may be able to adapt to warming conditions faster than their hosts, while some hosts, including beetles, have shown enhanced resistance to bacterial infections after brief exposure to extreme heat.

“I think we kind of assumed that heat waves would just increase diseases,” McCartan said. But depending on the mix of factors, it can enhance or inhibit infection, she said.

Ultimately, the results reveal just the tip of the iceberg for what can happen as the planet warms and what the implications will be, she said. “This is a lot more complicated than I would have thought.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,