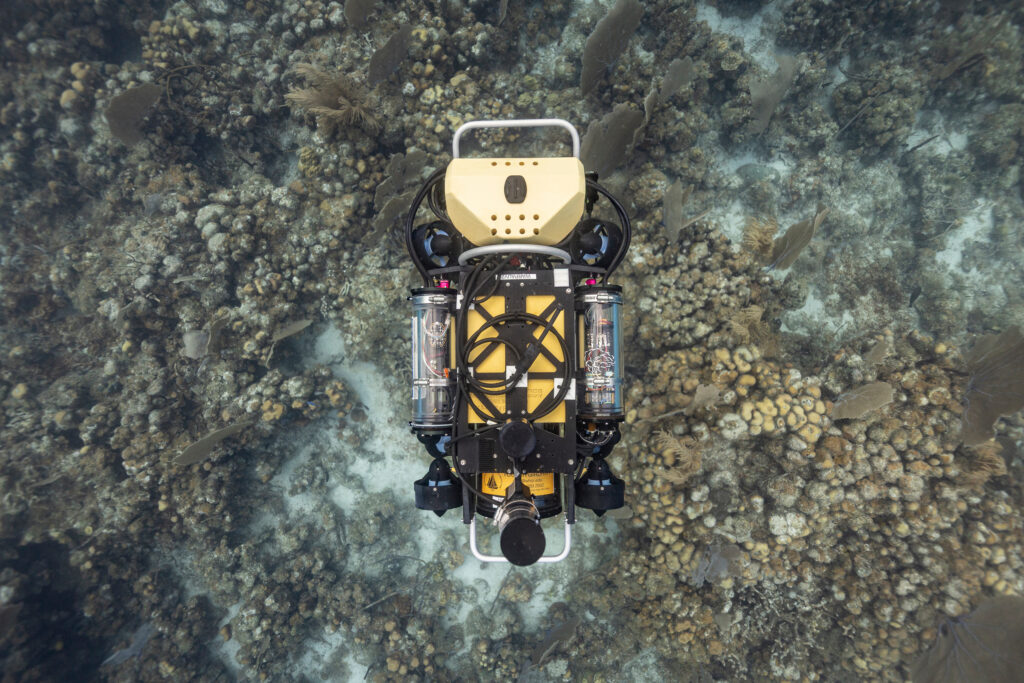

ST. JOHN, U.S. Virgin Islands—Thirty-five feet deep in clear turquoise waters, a three-foot-long yellow underwater robot maneuvers over a coral reef at a popular snorkeling site named Tektite.

At the surface, computer scientist Yogesh Girdhar and a team of engineers from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hover over a computer on an inflatable research boat, tracking a live feed of the autonomous vehicle’s movements to monitor its ability to navigate the uneven seascape and collect critical data on coral reef health.

The AI-powered robot is equipped with multiple cameras, underwater recording devices called hydrophones and other scientific instruments designed to assess signs of heat stress on reefs, identify biodiversity hotspots and search for rare species like pillar corals, which have nearly been wiped out by disease in the Caribbean.

“It’s a Curious Underwater Robot for Ecosystem Exploration. That’s what CUREE stands for,” said Girdhar, who leads the Autonomous Robotics and Perception Laboratory (WARPLab) at the Cape Cod-based research institution. And it’s one of the latest technologies the nonprofit is developing as part of its Reef Solutions initiative to expedite and improve reef monitoring and restoration efforts worldwide before it’s too late.

“Coral reefs are in a crisis scenario and action to conserve and restore them needs to be accelerating,” said Amy Apprill, a coral reef microbiologist who leads the initiative, which brings together a group of diverse experts in marine biology, chemistry, engineering, oceanography and computer science to create complementary tools that can better assess threats to reefs and even begin to rebuild them.

As of now, Apprill said, “We are on the trajectory to lose many of our reefs as we know them by 2050.”

Investing in Coral Solutions

Currently, more than 80 percent of the world’s reefs are experiencing the worst global bleaching event in recorded history, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s coral reef watch program, which uses satellite and in-situ data to forecast and observe threats to these ecosystems. The event began in 2023 due to rising ocean temperatures and is showing no signs of retreat. More than 83 countries and territories are affected. Bleaching occurs when ocean water temperatures become too warm and cause corals to expel the algae living in their tissues, turning their color white.

As world leaders gather this week at the United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice, Apprill said it’s imperative they join forces with scientists and community partners to reverse this ecological disaster.

“It is most important for the UN Ocean Conference leaders to recognize that many people, institutions, partnerships and financial components need to come together to successfully implement any coral reef solutions that [Woods Hole] or other scientists have developed,” she said. “Science and engineering are critical components to solutions for coral reefs, but we also need these partnerships and people invested in the solution for it to be successful and long-lasting.”

Last week, an 18-member international scientific committee of the One Ocean Science Congress also issued an urgent call to heads of state and government attending the UN summit to invest in cost-effective, scalable science and technology that will help halt the loss of tropical reefs and restore 30 percent of degraded ones. That’s mandated by the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, an international agreement adopted by 196 countries in 2022.

The One Ocean statement also demanded financial resources be dedicated to restoration initiatives led by Indigenous and local communities on the frontlines of dealing with the direct effects of reef degradation.

Coral reefs support the livelihoods of more than 1 billion people. They also protect shorelines from storm surge and flooding. Without concerted effort by nations and scientists, the committee says, reefs face likely extinction due to climate change.

“This is the first marine ecosystem, and perhaps the first ecosystem on land, too, that is potentially subject to disappearance,” said oceanographer Jean-Pierre Gattuso, a member of the scientific committee and research director of the National Centre for Scientific Research, based in France.

To make sure this doesn’t happen, Woods Hole’s Reef Solutions team is trying its best to develop a low-cost “toolkit” of scientific instruments they can someday deploy around the world to rapidly assess threats to reefs and help them recover.

“Now, more than ever, we need innovation. We need testing of techniques, and we need people from different fields and with engineering capabilities as well to come together and to work collaboratively on this,” Apprill said.

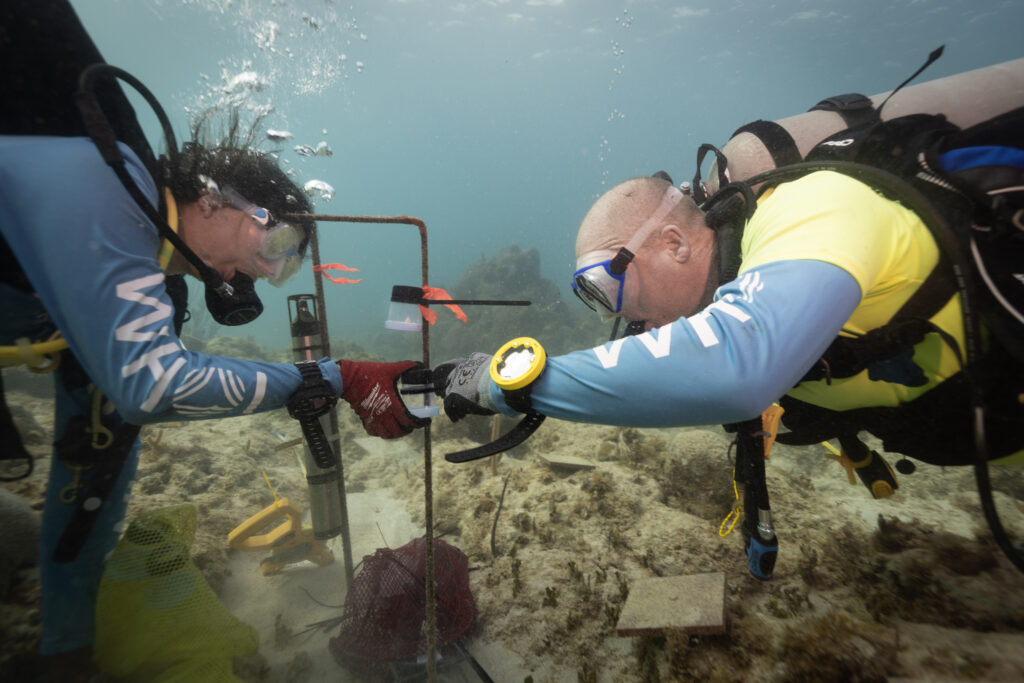

This spring, Apprill and the rest of the team visited St. John to test out some of their latest tools at the Virgin Islands Environmental Resource Station, a tropical research lab based in the Virgin Islands National Park. For two weeks, the rustic lab at the water’s edge at Lameshur Bay served as home base for testing, sampling and discussions around how the different tools they were developing could complement one another. They also shared them with a group of guests they’d invited to learn more about their work.

One of the instruments Apprill has developed is a type of water sampler she said helps detect bacteria and other microbes present near reefs that could be influencing their health. Another colleague, Colleen Hansel, who is a marine chemist, is experimenting with using crushed-up multivitamins that can be bought over the counter to boost coral fragment growth and their overall resiliency against disease and heat.

At the lab in St. John, she showed me how her team is infusing miniature donut-shaped rings made of calcium oxide and quartz sand with these vitamins and then placing small fragments of mountainous star corals in the center, atop a small plug. In the coming months, she will be outplanting these fragments on sections of degraded reefs to see if they’ll grow.

While it’s too soon to say how they will fare, her previous research has shown that surrounding the fragments with these vitamins, which will slowly be released over time, shows promising results.

“Sometimes the best answer is the simplest answer,” said Hansel.

The Curious Robot

CUREE is one of the team’s most complex diagnostic tools that Girdhar said can help replace the time- and labor-intensive processes conservationists have long used to survey reef health manually. These types of assessments, referred to as benthic and fish surveys, require scuba divers to identify each coral species, their abundance, size and density and count fish in certain areas. While they have been proven effective methods of monitoring reefs for decades and are still widely used, Girdhar said there’s a margin of error that can be eliminated with automated processes.

“When people do it, everybody’s trained differently,” he said. “Some have more bubbles and some produce less bubbles, and some scare fish, some don’t.” The manual process is also slow, both to collect the data underwater and analyze it later, he said.

CUREE, on the other hand, is processing data in real time with a higher level of accuracy. It can also cover larger areas faster than a human and scan for certain species. This is helpful when scientists want to know if there are any endangered species of pillar or brain corals still alive in an area, he said.

The robot’s multiple upward- and downward-facing cameras also allow the vehicle to take three photos per second of the reef below, and anything that swims in front of it. During a typical one-hour survey, Girdhar said it can capture up to 10,000 images, which can be used to produce 3D maps of reefs that show where bleaching has occurred.

Using artificial intelligence, CUREE can also lock onto a single fish and track it. In one underwater experiment, Girdhar and his team had it track a silver barracuda. “We kind of said, ‘Follow this barracuda,’” said Girdhar. “Then it took us for a long tour around that region to places we have never been.”

For at least 100 meters over the course of 10 minutes, CUREE followed the fish through deeper waters until it returned to the same spot it began its journey.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThis sort of automated observation of fish around reefs can help scientists determine how fish are using the reef and interacting with one another. “If you can follow them around, they can show us what’s happening,” said Girdhar.

The hydrophones attached to the vehicle can further support these observations by listening to fish, most of which make low-frequency sounds. By listening for these and determining the direction from which they’re coming, Girdhar said biodiversity “hot spots” can be detected that otherwise might have gone unobserved.

Sounds of the Reef

Bioacoustics, or the study of animal sounds, can play a significant role in reef restoration, according to Aran Mooney, a marine biologist at Woods Hole who is also part of the Reef Solutions team. He specializes in bioacoustics of marine organisms and has studied reef health and biodiversity through underwater soundscapes since 2012 in the U.S. Virgin Islands. There, he’s led the longest ongoing effort to monitor reef acoustics in the world.

But he’s not only recording reefs. Last year, he published a study that proved some species of coral larvae, including golfball coral, can be encouraged to settle in certain areas upon hearing sounds of healthy reefs. “We have this superpower,” he said.

Now, he’s using a device he calls the Reef Acoustic Playback System, or RAPS, to broadcast these sounds in degraded areas in the U.S. Virgin Islands that the team would like to try to restore.

He’s working with oceanographer Weifeng Zhang, also known as the “underwater weatherman” by some of the team, to help determine where coral larvae are likely to drift and stick around long enough to settle, based on currents and other ocean dynamics. Knowing this will help the team select sites that will be most suitable for placing the sound systems.

One is a desolate area called Salt Pond. In April, I snorkeled with Mooney there; only patches of algae-covered coral rubble littered the sandy bottom. But it was a perfect testing ground for recruiting coral larvae that would someday drift into this cove.

He pointed out a sandy patch where he’d installed a solar-powered underwater speaker weighed down by a cinder block and signaled for me to listen. Suddenly, I began to hear a chorus of crackling sounds made by snapping shrimp, spiny lobster, squirrel fish and grouper that Mooney had recorded previously at Tektite reef, which remains one of the most resilient and vibrant reefs in St. John.

These were the sounds that he hoped someday might lure new coral larvae to settle and begin to rebuild reefs of the future.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,