NICE, France—The deep sea—Earth’s largest and least-explored biome—is taking center stage at the United Nations Ocean conference this week, where marine experts are demanding world leaders end bottom trawling for fish and impose a moratorium on deep sea mining.

Bottom trawling has evolved into a largely unregulated commercial practice in which vast weighted nets are dragged across the seafloor to catch cold-water shrimp, cod, halibut and other bottom-dwelling marine life.

“It’s the most destructive fishing practice out there,” said Lissette Victorero, an ecologist and expert on deep sea fisheries management, who is attending the conference. A new documentary, Ocean with David Attenborough, was released to coincide with the conference, and Victorero said it captures the scale of ruin by industrial trawlers. “Most people have now seen it with their own eyes,” she said.

The documentary presents extensive footage of bottom trawling off the coast of Britain and Turkey. As a multi-ton net razes the seabed, corals, sponges and seagrass are mowed down, fish, squid and sting rays are uprooted, tossed and crushed into the net.

“What you’re seeing is animals flying out in every direction,” Victorero said. “It’s almost like a horror film.” The ocean conference, which runs from Monday to Friday, comes months before the pivotal U.N. climate conference in Belém, Brazil, known as COP30, which will seek consensus on the impending risks and costs of climate change.

In preparation for that conference, Brazil and France this week launched an initiative called The Blue NDC Challenge, which calls on countries to integrate the ocean into their “nationally determined contributions,” which are national action plans for climate change. The plans are key to the U.N. goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius. So far, Australia, Fiji, Kenya, Mexico, Palau and the Republic of Seychelle have joined the effort. The COP30 is set for November.

The ocean conference this week underscores a growing concern for marine dangers including plastic pollution, warming temperatures that bleach coral reefs, overfishing and unregulated fishing. Victorero is among more than 150 scientists at the conference who signed a joint open letter to the U. N. Secretary General that urges heads of state and government to focus on fragile deep sea ecosystems and the risks of bottom trawling on seamounts, or submarine mountains, in international waters.

At least 100,000 of these geological formations exist in the world. Most are extinct volcanoes and support an abundance of marine life. Some serve as critical resting stops for migratory species like endangered sperm whales and sea turtles. Some species use them as navigation points. Hammerhead sharks are known to travel from one seamount to another where they aggregate and mate, according to the nonprofit Marine Conservation Institute, based in California.

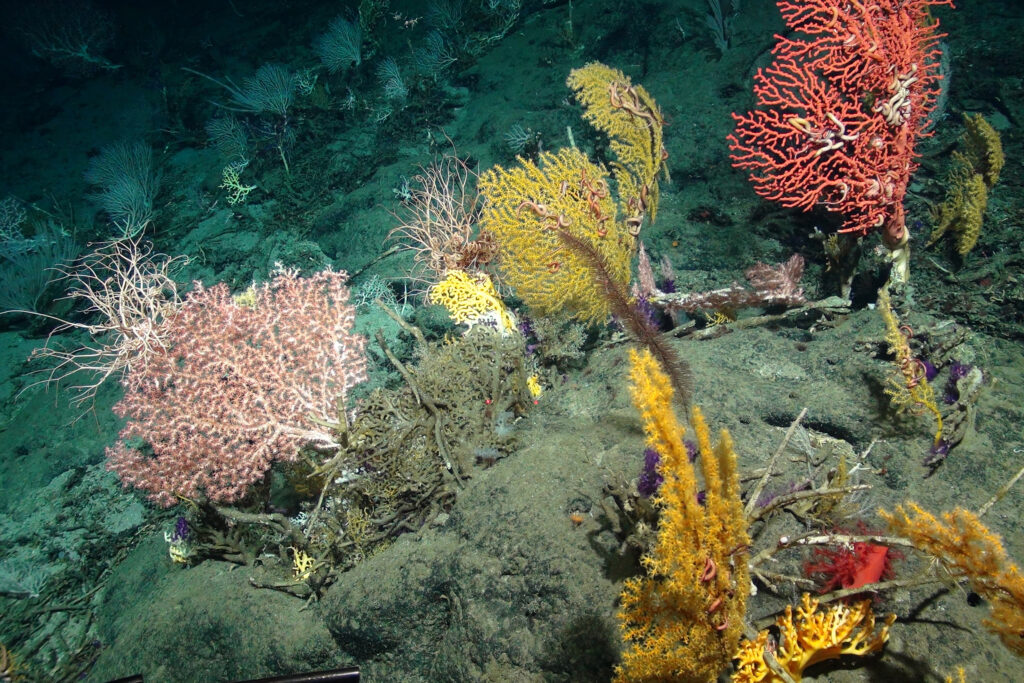

Cold-water coral reefs also grow on underwater formations, said Victorero, who is a scientific advisor for the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, an alliance of more than 100 international organizations. Some of the oldest living animals on the planet are black corals, named for their dark skeletons,which grow on seamounts. It’s estimated some coral colonies are 7,000 years old, Victorero said.

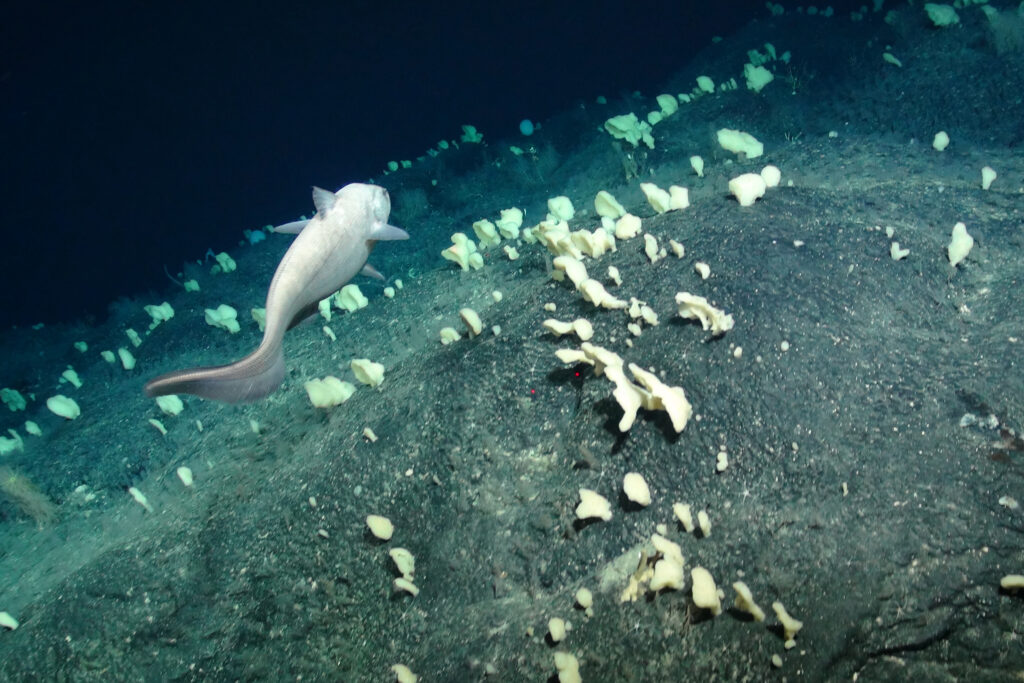

But these ecosystems, like those on abyssal plains of the deep seabed, are increasingly threatened by commercial trawlers.

“It’s like taking a giant mower and cutting them down, and they don’t recover for a very, very long time,” said Lisa Levin, a marine ecologist and professor at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, who will speak at the conference.

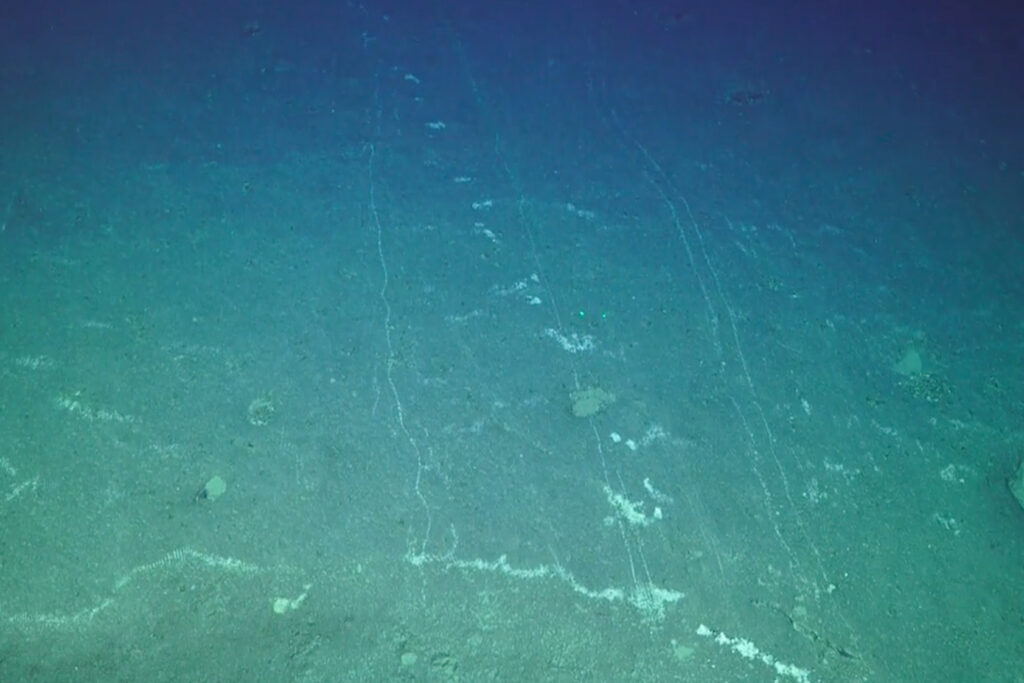

Scars from bottom trawling on seamounts can still be seen 40 years after the damage was done, Victorero said.

The deep ocean, where light typically ceases to penetrate, plays a critical role in regulating the global climate and buffering effects of climate change. It is the largest carbon sink on earth, according to a scientific paper co-authored by Levin.

Levin and other scientists are worried about the potential for deep sea mining to wreak damage much like trawling, and seamounts are most vulnerable. Cobalt-rich ferromanganese crusts often occur on the flanks and summits of these structures. Mining the minerals from this formation would be devastating, Levin said. “It’s probably as, or more destructive than bottom trawling, but it hasn’t happened yet,” she said. “We have an opportunity to protect seamounts from seabed mining at this point, if we want to.”

No commercial deep sea mining has happened yet. But President Trump issued an executive order in April that charges the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration with developing processes to expedite company applications to mine the deep sea in international waters. Trump’s action appears, to many at the ocean conference, to be an attempt to circumvent international law and act unilaterally.

According to the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, the only authority that can approve mining in areas beyond nations’ national jurisdictions is the International Seabed Authority, composed of 167 member states plus the European Union, who are still in the process of developing a mining code for the ocean.

On Monday, 24 countries issued a joint statement in support of a “pause on the exploitation of the deep sea bed” and called for “accelerated scientific research of the deep sea.” The statement also asked its partners to promote respect for international law. Pradeep Singh, an ocean governance expert at the Oceano Azul Foundation, a Portugal-based foundation, said such declarations are important even if not legally binding.

“If states are opposed to this activity, it would then mean that financial institutions, banks and so on, would also have to take that into consideration,” said Singh, who spoke at a conference panel Monday.

Protected Areas Under Siege

According to Victorero, seamounts are protected by a U.N. resolution that was adopted in 2006. But a lack of enforcement and oversight of fishing activity in international waters has jeopardized the ecosystems, she said.

“They’ve had 20 years to establish rules and operationalize all of these governance frameworks, and it still hasn’t happened,” Victorero said. “This letter is a renewed poll, kind of building on the legacy of the previous letter about saying: ‘Hey, we have 20 years more of science, we have 20 years more of knowledge, and you’ve had time, you’ve had all the time in the world to do the right thing.’”

Similarly, many marine protected areas around the world, which limit or prohibit human activity to conserve or restore certain species or ecosystems, are trawled and increasingly so in the past few years.

In Europe, at least half of the seabed in some areas is trawled each year, according to a report co-authored by Enric Sala, a marine ecologist from Spain who will be speaking at the conference this week. Sala was a scientific advisor to the Attenborough documentary and credited in the film.

“Hundreds of boats are fishing, are bottom trawling, in marine protected areas in Europe every day, and people don’t know about it,” Sala said in an interview before the conference.

People don’t understand that their shrimp or fish dinners cost the lives of hundreds of other marine life, he said. Up to 75 percent of the total catch of a bottom trawl can be bycatch, or non-target species. “We’re talking about seashells, starfish, sponges, in some places, deep sea corals, skates, rays,” he said. Mega fauna including sea turtles and dolphins are also often entrapped—and left for scrap.

“If they’re fishing for shrimp, they will pick the shrimp and discard the rest of the animals overboard,” Sala said. “Imagine if people were told that companies are bulldozing the forests in Europe’s national parks and also that this industrial hunting operation is killing all the animals inside. People will be outraged.”

Sala’s study, released in March, estimates the economic cost of bottom trawling in Europe’s waters to reach more than $12 billion annually when tied to massive carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from disturbed seafloor sediments.

The Ocean-Climate Nexus

The deep ocean holds a solution to curbing climate change, experts said. Excess carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is transferred to the deep sea through a series of biological processes where it can be stored for hundreds to thousands of years, if it is not disrupted.

In the last 10 years, Singh said new research on the deep sea has put this previously overlooked ecosystem in the spotlight.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“It has taken a while to get the international community to take the deep sea seriously,” he said. But that is shifting, he said, thanks to increasing technology and research that has shed light on this ecosystem in the last 10 years.

“The science is very clear that it’s the deep ocean that’s really sustaining the health of the ocean, but not just the ocean, the climate as well,” Singh said.

This week, during the conference, an increasing number of governments are expected to take stronger stances on bottom trawling and deep sea mining. President Emmanuel Macron of France said in a conference plenary session that he would “limit” bottom trawling in national waters—not a ban as some advocates hoped.

According to Oceana, an international advocacy organization based in Washington, Macron agreed to protect French waters but mostly in places where bottom trawling does not occur. Macron’s commitment would cover 4 percent of French waters rather than the current 0.1 percent, the organization said. Oceana campaign director Nicolas Fournier, in a press release, called Macron’s effort “symbolic.”

“President Macron built expectations that the French government would finally act against bottom trawling in marine protected areas—yet these announcements are more symbolic than impactful,” Fournier said. He added the measure will “do little to support the local communities and fishers that rely on them.”

Advocates are feeling hopeful, however, that a number of countries will ratify what is often called, in conference jargon, the BBNJ Agreement. BBNJ is an acronym for a U.N. convention and law which outlines the “Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas beyond National Jurisdiction.”

The BBNJ Agreement is also known as the High Seas Treaty or Global Ocean Treaty. It provides a mechanism for establishing marine protected areas in international waters and adding extra protection for vulnerable ecosystems like seamounts against destructive activities like bottom trawling and deep sea mining.

Before the conference, more than 30 countries and the European Union had ratified the treaty. Late Monday, conference officials announced that 18 more countries had ratified, totaling 49 ratifications. The agreement needs 60 countries to make it legally binding.

This story was updated June 10, 2025, with the late developments on ratifications.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,