JASPER, Ala.—If federal funds designated for Alabama’s mining regulator dry up—there is a 16 percent cut in state grants now being debated in Congress—director Kathy Love believes she has a quick and compelling rebuttal.

Alabama has primary oversight, as do 14 other states, over its mines but it needs the federal government to help pay the cost. If there’s not enough money to do the job right, she said, the federal government can take over the reins as regulator.

The Department of Interior makes that clear, or at least that is how she reads Title V of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act. And “nobody wants that,” said Love, who heads the Alabama Surface Mining Commission. She met Thursday with commissioners and explained some of the budget woes still brewing in Washington.

Love said the agency was lobbying for funds to be maintained. In an interview after the meeting, Love warned that, unless that happens, the commission may be forced to choose: ask the Alabama Legislature to dole out supplemental funding or watch the federal government take over.

“So we’ve got to get busy in D.C.,” said Love, indicating that the state will need to call on the Trump White House and Congress to change their minds.

Alabama has among the highest number of coal mines in the country, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, behind only traditional mining states like West Virginia and Kentucky.

This is how the system is supposed to work: Title V of the federal surface mining act provides federal grant funding for states to operate their coal regulatory programs.

It is typically the primary funding for operational costs of state regulators that oversee active mines across the country. States may supplement these dollars, but the federal government has been the pivotal source of regulatory funding.

But now President Donald Trump has proposed steep cuts to funding across agencies, including grant funds that states rely on for basic regulatory needs.

Currently, the budget winding its way through Congress would reduce Title V funding from $62.4 million to $52.4 million.

That would seriously impact state mining regulators across the country, said Bob Mooney, who worked both as a state and federal mining regulator for decades.

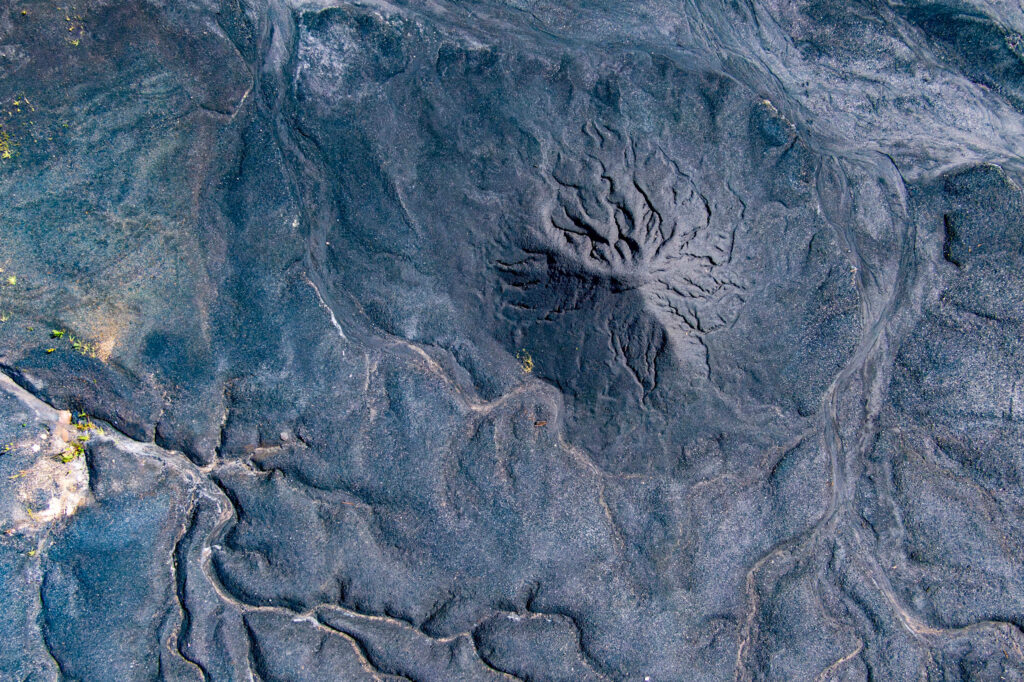

“That would be hard to deal with, especially in Alabama, where there’s such a robust program,” Mooney said. About 92 percent of the coal produced in Alabama comes from seven underground mines, and the rest comes from 13 surface mines. About 90 percent of Alabama’s coal is exported to other countries, according to federal data.

Beyond the budget woes, Alabama is currently in a court fight over a Biden administration rule that expanded the rights of citizens to complain to the federal government about mine management and care, and, in turn, for federal regulators to investigate.

At Thursday’s meeting, an attorney for the state mining regulator said Alabama and other states opposed to the citizens’ rights law are asking for a federal court to rule immediately against its enforcement.

In December, Alabama found itself on the receiving end of what is called a “10-day notice”—a written determination from federal regulators requiring the state to take action on a mining-related problem, in this case to improve monitoring and bolster methane and subsidence checks. The notice followed a fatal March 2024 explosion in the central part of the state at the Oak Grove Mine. W.M. Griffice, an Alabama grandfather, died from injuries suffered when his home, atop the mine, blew up.

Following an Inside Climate News investigation into state and federal inaction, federal officials ordered Alabama to ensure mine companies filed safety plans that include protocols around the release of potentially explosive methane from their underground operations.

Earlier this year, at the request of mining lobbyists, Love extended the deadline for companies to submit updated plans. Thursday, she told commissioners that the companies are “actively preparing” new submissions, now due Sept. 30.

Lisa Lindsay lived a stone’s throw away from the elderly Griffice, who was a friend. She listened to what the state said it was doing to improve safety—and she said she doesn’t believe state regulators would have required methane monitoring plans without federal intervention.

“What they do is always just lipstick on a pig,” Lindsay said after the meeting.

In an interview after that meeting, Love refused to say whether her agency would have required methane monitoring in the absence of the federal notice.

“I’m not getting into that discussion,” Love said.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,