President Donald Trump landed this week on an airstrip in the Florida Everglades for a visit to a swiftly assembled detention facility that federal and state officials say will house 3,000 undocumented migrants, as the president aims to fulfill his plans for mass deportations.

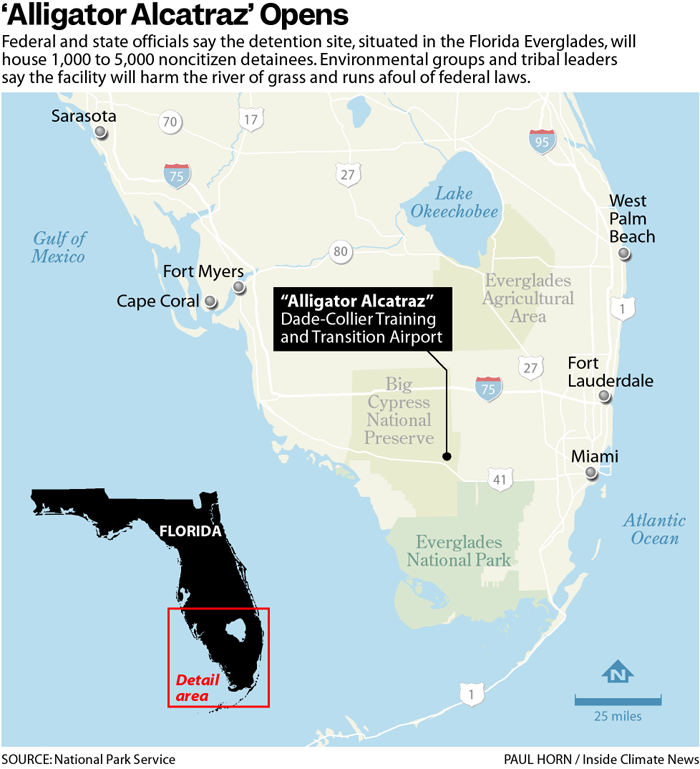

Dubbed “Alligator Alcatraz” for its location within a swampy thicket of the Big Cypress National Preserve, the site will be reserved for the worst offenders, Trump said as he congratulated federal and state leaders on the speedy completion of the project during a site tour and roundtable discussion Tuesday.

“I looked outside, and it’s not a place where I want to go hiking anytime soon,” said the president. “But very soon this facility will house some of the most menacing migrants, some of the most vicious people on the planet. We’re surrounded by miles of treacherous swampland, and really the only way out is deportation.”

The facility will house detainees as they await due process, before they are sent out of the country, said Kristi Noem, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security. She said it took eight days to complete and suggested more states should follow Florida’s lead.

“It’s exactly what we need to be perpetuating in other states,” she said. “We are going after murderers and rapists and traffickers and drug dealers and getting them off the streets and getting them out of this country. The worst of the worst come here.”

The detention center features 158,000 square feet of housing within structures capable of withstanding a strong category 2 hurricane, said Kevin Guthrie, director of the Florida Division of Emergency Management. The facility could accommodate more inmates as needed, he said. The airstrip where the president landed can be used to receive and deport the prisoners.

“It’s a one-stop shop,” said Gov. Ron DeSantis, who ran against Trump in the 2024 GOP primary.

The site’s location within a protected area of the Everglades has horrified those engaged in the plight of the fragile watershed, which spans much of the peninsula and is responsible for the drinking water of some 12 million Floridians. The facility is situated partly within the Big Cypress National Preserve, the nation’s first preserve established to protect the sensitive marshes and sloughs here that are part of the river of grass. Between 100 to 200 members of the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, Seminole Tribe of Florida and other native people of Miccosukee and Seminole heritage live in 15 villages within the preserve. For them the land is sacred.

“The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is opposed to the proposed facility, given the impacts on the Big Cypress and Tribal communities living within it,” said Miccosukee Chairman Talbert Cypress in a statement provided to Inside Climate News. “We have reached out to both the DeSantis and Trump administrations to determine a path forward.”

A coalition of environmental groups filed a lawsuit aimed at stopping the detention center on the grounds that it has not undergone any environmental reviews required under federal laws such as the Endangered Species Act or the National Environmental Policy Act, which calls on federal agencies to prepare environmental impact statements on potential projects. The groups say the project was rushed and that there has been no opportunity for public comment.

“The hasty transformation of the Site into a mass detention facility, which includes the installation of housing units, construction of sanitation and food services systems, industrial high-intensity lighting infrastructure, diesel power generators, substantial fill material altering the natural terrain, and provision of transportation logistics (including apparent planned use of the runway to receive and deport detainees) poses clear environmental impacts,” the complaint says.

“The Defendants, in their rush to build the center, have unlawfully bypassed the required environmental reviews. The direct and indirect harm to nearby wetlands, wildlife, and air and water quality, and feasible alternatives to the action, must be considered under NEPA before acting.”

The litigation was filed in U.S. District Court in the Southern District of Florida on behalf of Friends of the Everglades and the Center for Biological Diversity, by a team of attorneys that includes Earthjustice. In addition to Noem and Guthrie, it names as defendants Todd Lyons, acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and Miami-Dade County, which owns the property. The DeSantis administration took control of the site in June from Miami-Dade County under a 2023 executive order the governor issued that declared a state of emergency over immigration.

The Department of Homeland Security provided a statement to Inside Climate News characterizing the complaint as a “lazy lawsuit” and pointed out the property already was developed before construction on the facility began. The agency also shared a news release highlighting arrests in Florida of noncitizens that it said were convicted of crimes such as homicide, producing and distributing child pornography and sex crimes involving children.

The DeSantis administration denied that the detention center would harm the environment.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“Utilization of this facility for these purposes will not incur the removal of vegetation, additional paving, or permanent construction,” according to a statement provided to Inside Climate News. “On the existing airstrip, FDEM will utilize temporary buildings and shelters consistent with similar applications during natural disasters. Utilities such as water, sewage, and power will be facilitated by mobile equipment that will be removed at the completion of the mission.”

Miami-Dade County Mayor Daniella Levine Cava, in a statement provided to Inside Climate News, shared the concerns of environmental groups.

“Like so many across our community, we are outraged by the state takeover to build a massive detention center in the middle of the Everglades—a process with very little transparency and too many unanswered questions for our residents.

“I have expressed my concerns about the environmental risks of this operation to the Everglades—an ecosystem vital to our clean water, economy, and tourism industry. While the state claims the site is self-contained, it remains unclear how a facility of this scale can avoid impacts to such a fragile environment.”

The environmental groups also argue in their lawsuit that the site will undermine a $23 billion federal and state effort to restore the Everglades. The effort is among the most ambitious of its kind in human history, and among its goals is to secure the drinking water supply in a region that is pressured by climate change and hotter temperatures and rising seas. The Everglades begins in central Florida with the headwaters of the Kissimmee River and includes Lake Okeechobee, sawgrass marshes to the south and Florida Bay, at the peninsula’s southernmost tip. Draining vast swaths of the region has made modern Florida possible and threatened the delicate watershed.

The environmental groups contend the facility will cause further harm to sensitive wetlands in the area and multiple species listed as endangered or threatened, including the Everglades snail kite and Florida panther, the official state animal.

“It feels incredibly open and freeing, I think, to be in Big Cypress,” said Elise Bennett, Florida and Caribbean director and attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity. “It kind of feels like going into another world. I think just the quiet, and for me there is a spiritual feeling, of the idea that you’re in a place where you might cross the same path that a Florida panther did, or that you might get to see an Everglades snail kite hunting.”

The site has a long history of controversy, beginning with a 1968 proposal to build what planners envisioned at the time would be the world’s largest airport, called the Everglades Jetport. Backlash from conservationists would stop the project after the construction of just one runway and inspire Florida’s modern Everglades movement. The opposition also led the Department of the Interior to commission a report to assess the ecological impacts of the project, one of the nation’s first environmental impact statements. The report prompted former Gov. Claude Kirk to withdraw his support from the project, a position later adopted by former President Richard Nixon. Until recently the runway had been used for aviation training.

“The Big Cypress National Preserve was born of that fight,” said Eve Samples, executive director of Friends of the Everglades, an organization that was founded by Marjory Stoneman Douglas as part of the campaign to stop the jetport. “We’ve come full circle. We’re having to fight some of the same battles that we fought back then, and in many ways they feel more urgent, more dire. It’s really laughable to hear some of our state leaders characterize this action as having no environmental impact because it absolutely does and it needs to be analyzed.”

In a letter to Mayor Levine Cava, Guthrie said the state’s use of the property would last “no longer than the duration of the state of emergency.” Florida officials have characterized the detention center as temporary, although during Tuesday’s roundtable discussion Trump suggested the facility could be “morphed into your prison system.” He also said citizens who have committed crimes could be housed at the detention center, too.

“I think we ought to get them the hell out of here, too,” he said. “These are sick people.”

The Department of Homeland Security has indicated the federal government would provide $450 million annually for the state to operate the facility, according to the environmental groups’ lawsuit. DeSantis said Tuesday a second site is in the works to house 2,000 undocumented migrants at Camp Blanding, a training center for Florida National Guard units in north Florida. The governor discounted environmental concerns.

“You are literally doing this on concrete that is already here, so I don’t think those are valid or even good faith criticisms because it’s not going to do anything to impact the Everglades,” said DeSantis, whose administration has invested billions of dollars toward Everglades restoration. “I think it’s just people who don’t want to see illegal inmates deported, and that’s their ideology.”

During his visit Tuesday, Trump toured an intake facility and medical facility and chatted with construction workers and employees of the Florida Division of Emergency Management. He also stopped inside a housing building.

“The site was one of the most natural sites,” the president said. “It might be as good as the real Alcatraz.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,