The Trump administration has cancelled a $417,000 federal grant that would have funded research on the social and economic impacts of biogas production from industrialized swine operations in North Carolina.

Over several years, scientists from RTI International in Durham and the Gillings School of Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill had planned to continuously monitor the air, and periodically sample rivers, streams, and private drinking water in Duplin and Sampson counties. The study would also have collected health data in the communities.

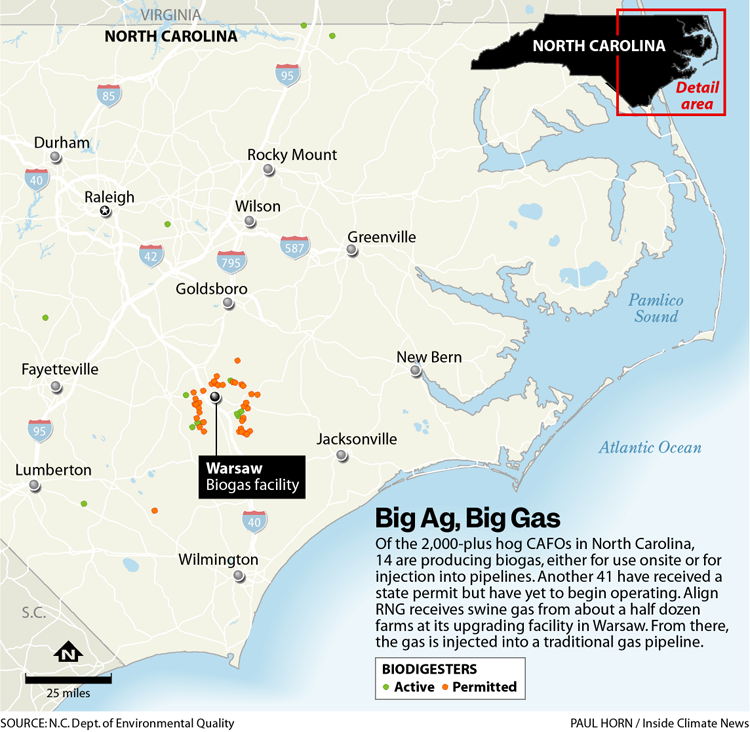

Duplin and Sampson rank first and second in the nation, respectively, in the number of swine farms, according to a University of Michigan study. They account for 4.2 million hogs on roughly 900 farms, state environmental data shows, a small percentage of which have received state permits to produce biogas.

Census data show tracts near these concentrated animal feeding operations—CAFOs—are predominantly Black, Indigenous or Latino.

The research is important because swine gas operations are proliferating in North Carolina. Yet there is scant data on the environmental and health effects near these facilities, according to the RTI and UNC scientists.

The community research conducted in Duplin and Sampson counties on the biogas production project was sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and National Institute of Environmental and Health Sciences (NIEHS).

The biogas study was one of at least 1,700 projects that lost funding earlier this year after the Trump administration terminated $783 million in grants at NIEHS’ parent agency, the National Institutes of Health. Although it is unclear if the biogas study was singled out for its environmental justice focus , similar projects were targeted.

The U.S. Supreme Court last month upheld the administration’s cuts by a 5-4 vote. A lower court judge had blocked the cancellations on the grounds that they were discriminatory.

The North Carolina scientists, led by Crystal Lee Pow Jackson, had conducted one round of private well sampling and collected initial air quality data, but had yet to sample near an active swine gas operation when the Trump administration canceled the grant.

“We couldn’t complete the full research but there is valuable baseline data in this,” said Courtney Woods, an associate professor in UNC’s Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering. She also leads programs at the university in Environment, Climate and Health and Health Equity and Social Justice.

Major pork producers tout biogas as a solution to the industry’s methane problem. In 2018, swine manure emitted 970,000 tons of methane nationally, federal data show, second only to dairy.

Methane is short-lived in the atmosphere, but it inflicts more damage to the climate than carbon dioxide. Over 20 years, methane is 86 times more potent at warming the planet than CO2, which remains in the atmosphere for centuries.

Swine CAFOs generate biogas by capping waste lagoons, capturing the methane they emit and injecting the gas into a pipeline. Some CAFOs use the gas to power farm operations.

Yet the industry’s position doesn’t account for pipeline leaks. And in North Carolina, swine biogas systems still pump extra feces and urine into a second open-air lagoon; from there, the waste is sprayed on fields as fertilizer. Fecal contamination can seep into the groundwater and private drinking water wells from the spraying; methane, ammonia and hydrogen sulfide from the lagoons still enter the air, unabated.

Align RNG, a partnership between Dominion Energy and Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork producer, receives swine gas from a half dozen CAFOs in Sampson and Duplin counties, according to state records from 2024. The farms ship their gas through 30 miles of low-pressure pipelines to Align RNG’s upgrading facility near Warsaw, a small town off Interstate 40 in Duplin County.

Align RNG did not respond to an email summarizing Inside Climate News’ reporting and inviting comment.

The upgrading plants are necessary because swine gas has a different chemical composition than gas derived from fossil fuels. Constituents such as hydrogen sulfide, nitrogen,ammonia and carbon dioxide must be removed before the gas can be injected into a traditional pipeline. These “tail gases” are scrubbed of hydrogen sulfide and burned in an enclosed flare.

Once the swine gas is upgraded, Align RNG injects it into a nearby pipeline owned by Piedmont Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Duke Energy, which uses it to generate electricity.

Align RNG estimates as many as 19 swine CAFOs could eventually ship their gas to the plant in Warsaw. Kraig Westerbeek, then-vice president of Align RNG, told the state Division of Air Quality in 2020 that the participating farms would reduce their collective methane emissions each year by 150,000 tons, measured as carbon dioxide equivalent. CO2 equivalent is a unit of measurement that standardizes the global warming potential of different greenhouse gases.

The company plans to build a second upgrading plant near Bowdens, also in Duplin County. It would accept gas from as many as 35 swine CAFOs, according to the Align RNG website. Construction is expected to finish by late 2026. The company has yet to apply for an air permit, according to a state database.

State records show that there are 55 swine CAFOs with biodigester permits. Of those, 14 have completed construction and are generating swine gas, or able to. Another 41 have yet to notify the state that they’ve finished construction. The state is reviewing permit applications for another 30 farms.

Since 2012, Duke Energy, municipal utilities and electric cooperatives have been legally required to generate or source a small percentage, up to 0.2 percent, of their prior year’s total retail electricity sales from swine waste.

However, the N.C. Utilities Commission has delayed its implementation because “the technology of power production from swine waste continues to face challenges and that swine waste-to-energy projects continue to experience operational difficulties,” a commission report from 2020 reads.

Blakely Hildebrand, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, filed a civil rights complaint with the EPA Office of External Rights Compliance four years ago over the biogas permits. The law center submitted the complaint on behalf of its clients, the Duplin County NAACP and the North Carolina Poor People’s Campaign.

The complaint alleged that, in issuing the biogas permits, the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality discriminated against Black and Latino residents in eastern North Carolina because the facilities had a disparate, harmful impact on those communities.

Since 2022, SELC and the state have been negotiating to resolve some of the allegations, Hildebrand said.

“We’ve not yet resolved the complaint,” Hildebrand said, “and the Trump administration has taken several steps to undermine civil rights law and environmental justice policy.”

In the spring, EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin canceled more than 400 environmental justice grants. In late August, the EPA fired more than two dozen remaining staffers in the now-defunct Office of Environmental Justice and External Civil Rights.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced last month it would stop funding wind and solar power installations on farmland.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowThe biogas conditioning plants are also sources of pollution. Align RNG’s Warsaw plant could emit 64 to 220 tons of pollutants each year, according to the company’s air quality permit.

Sulfur dioxide accounts for more than 75 percent of the potential emissions produced during biogas processing. Short-term exposure to sulfur dioxide can harm the respiratory system and make breathing difficult, according to the EPA. People with asthma, particularly children, are sensitive to these effects.

Precise figures from the upgrading facility aren’t publicly available because Align RNG doesn’t have to file an emissions inventory until 2028, state records show.

Earlier Air and Water Testing

RTI and UNC scientists presented limited results from their study in August in Sampson County at a meeting of EJCAN, an environmental and social justice group in Clinton. The preliminary data reflected the baseline environmental conditions because the biogas project is not in full operation, an RTI spokesperson said.

All of the 11 surface water sampling sites tested before the grant cancellation contained total coliform and E. coli bacteria at least once. In some cases, levels of E. coli exceeded state surface water standards.

(The N.C. Department of Environmental Quality currently uses fecal coliform as an indicator, but is switching to E. coli to align with EPA methods.)

Levels of nitrite, ammonia and nitrate concentrations were below surface water standards. However, phosphorus, which can supercharge harmful algal blooms, peaked at more than 30 times the levels at which algae could begin to multiply.

One-time air monitoring outside 13 homes within two miles of swine CAFOs, also conducted prior to the grant cancellation, detected nitrogen dioxide below National Ambient Air Quality Standards.

The scientists also found ammonia and hydrogen sulfide at similar levels reported by other studies in North Carolina, although there are no state standards for those compounds in for community ambient air. There were brief spikes of fine particulate matter, known as PM 2.5, at unhealthy levels for a few hours, said Seung-Hyun Cho, the air monitoring project leader.

The scientists wanted to survey more community members about their views on swine gas operations, as well as the state of their physical and mental health. Yet despite the study’s limitations, residents were able to participate in the research, itself a valuable exercise. “We successfully engaged the community in environmental monitoring,” Courtney Woods, the UNC associate professor and researcher, said.

Most of the participants weren’t aware of the swine gas operations, Woods said. But they were concerned about persistent odor, health impacts and emotional stress of living near CAFOs in general.

While those surveyed said the hog industry provided economic benefits, Woods said, “they wanted clear answers on health impacts.”

The deleterious health impacts of living near swine CAFOs—even those without biodigesters—have been well documented. A University of Michigan study released last month found that census tracts near these facilities had 11 percent higher levels of PM 2.5 than those tracts without them, even when accounting for urban and industrial sources.

Epidemiologists have found that exposure to elevated levels of PM 2.5 is linked to asthma, cardiovascular disease, bronchitis, leukemia and Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers at the American Medical Association have found increases in overall death rates, heart attacks and lung cancer corresponding with increases in PM 2.5 levels. These health effects have been observed in residents as far as 11 miles from the farms.

Julia Kravchenko, an assistant professor of surgery and of population health sciences at Duke University, discovered similar trends in 2018. North Carolina communities located near hog CAFOs had higher all-cause and infant mortality, deaths due to anemia, kidney disease, tuberculosis, septicemia, and higher hospital admissions of low-birth-weight infants, Kravchenko found, but the study did not establish causality.

The Trump administration’s cancellation of the grant hampers the public’s ability to scrutinize the burgeoning industry. “I think communities have a right to know how their health is going to be affected,” Hildebrand, of the SELC, said. “And regulators need to know that as well, so that they can put protections in place to keep the environment safe and to ensure that the people who live near these facilities are kept safe as well.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,