When Southern Europe was hit by a catastrophic heat wave last month, it dominated global news cycles. Spain experienced its longest heat wave on record: lasting 16 days with temperatures reaching 109 degrees. By August 19, wildfires stoked by the heat had torched more than 40,000 acres in France. At the peak of the heat wave, 60 percent of Italian cities were placed under the highest alerts for deadly temperatures. The death toll from the heat in Europe is still being tallied, but includes a four-year-old boy who died of heat stroke in Italy.

When higher-latitude, and thus cooler, regions that haven’t prepared for health-threatening high temperatures endure waves of unusual heat, they become obvious examples of heat stress brought on by a warming climate. But places that we assume are always hot have also been burdened by more extreme heat, Joyce Kimutai, principal meteorologist and climate scientist at the Kenya Meteorological Department, said.

“There was the misconception that, because Africa is warm anyway, people are tolerant to the heat,” she said. “I think that tolerance level is now superseded.”

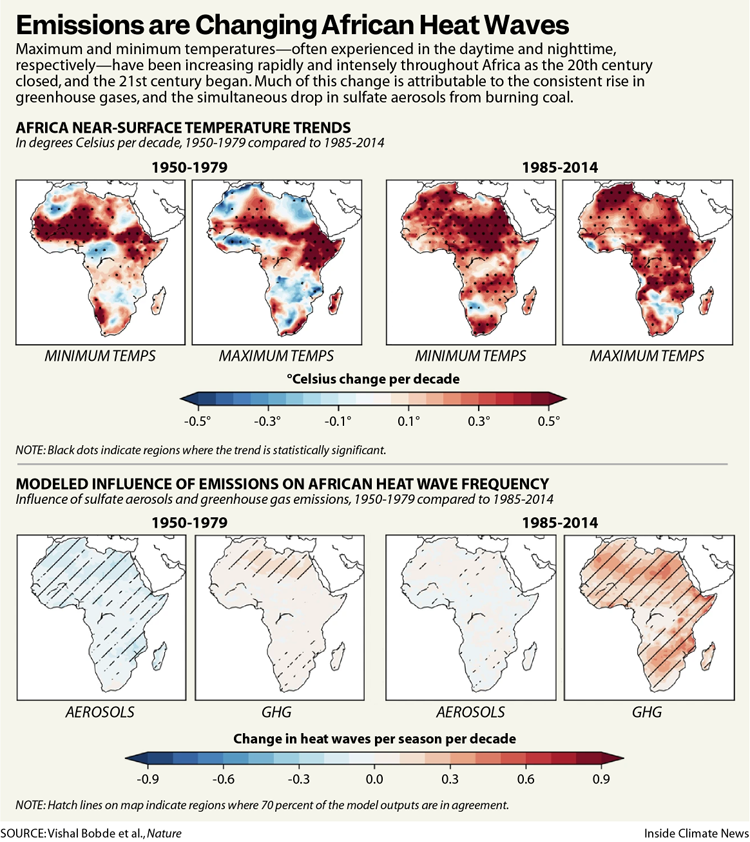

Recent research published in Nature has found that the frequency and intensity of heat waves throughout Africa have increased significantly since the end of the 20th century. But the steep upward trend in temperatures on the continent is due not only to increases in the emissions that warm the climate. A decline in emissions that cool the Earth’s surface is also increasing the heat.

As greenhouse gas emissions, like carbon dioxide, have been increasing, efforts to clean up energy supplies have led to a decrease in coal burning in many areas, including Africa. While reductions in coal burning substantially reduce how much carbon dioxide is emitted to warm the climate in the long term, they also reduce the emissions of sulfates that reflect some heat away from the Earth in the short term. The combination of long-term climate warming and short-term reductions in planet-cooling sulfates has increased the frequency and intensity of heat waves throughout the continent over the past 30 years.

As sunlight warms the Earth’s surface, the planet sends some of this energy back to space. Carbon dioxide, methane and even water vapor in the atmosphere hold some of that heat in like a blanket—the more of those greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, the warmer the blanket. But certain aerosols—like sulfate particles, which are emitted along with carbon dioxide when coal is burned—act like mirrors that reflect some solar radiation away from the planet, thus cooling it.

In Africa, sulfate emissions from coal-producing and consuming countries such as Zimbabwe, Democratic Republic of the Congo and Namibia increased until the late 1980s along with greenhouse gas emissions.

The sulfate emissions dampened local warming in Africa during the middle of the 20th century, Vishal Bobde, a third-year Ph.D. student in Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois-Chicago and one of the study co-authors, said. Before the 1980s, cooling aerosols and warming greenhouse gas emissions “were compensating each other,” he said. “So the net effect of humans was balanced out.”

In Western countries with longer legacies of industrialization, such as the United States and Great Britain, air quality regulations, coupled with increasing dependence on gasoline, reduced sulfate emissions as early as the 1970s, bringing localized warming to those regions before it was detected in Africa. In many African countries, coal use and consequent sulfate emissions didn’t start declining until the late 1980s, and were often driven by political unrest and economic collapse. The result should hypothetically increase heat wave frequency, Bobde said.

To test this hypothesis, Bobde and his co-authors used a combination of climate model assessments and observations to determine how heat waves have changed throughout Africa since 1950. They specifically examined the changes in daytime maximum temperatures, nighttime minimum temperatures and 24-hour maximum temperatures during the three warmest months of the year across every region in Africa, comparing the 30-year period from 1950 to 1979 with that from 1985 to 2014. While there was some warming of minimum nighttime temperatures and maximum nighttime temperatures from 1950 to 1979 over Saharan countries, tropical countries, such as Nigeria and Cameroon, showed evidence of some cooling. In the more modern period, only parts of Namibia and Botswana were spared from the heat, and the study found that large swaths of Africa had maximum temperatures increase by more than one degree Celsius.

Climate model simulations allowed them to distinguish between human and natural drivers of warming, said Kayode Ayegbusi, a PhD student in Earth and Environmental Sciences at the University of Illinois-Chicago and study co-author. From 1950 to 1979, sulfate emissions reduced extreme temperatures almost everywhere in Africa, shaving half a day off of heat waves and making them one degree Celsius cooler. In the humid Congo Basin, sulfate aerosols erased two heat waves per season, the research showed.

But in the 30 years spanning the turn of the millennium, sulfate aerosols had a muted impact on heat waves that was completely overwhelmed by warming driven by greenhouse gas emissions. From 1985 to 2014, northern African countries, such as Libya, Egypt and Sudan, and southern ones, including Mozambique and Zimbabwe, had an additional one and a half heat waves per season attributed to greenhouse gases.

Such increases in the duration and temperatures of periods of extreme heat can be deadly, as heat stroke and dehydration also increase in the exposed populations. While air conditioners and fans are often used to mitigate these conditions in wealthier countries, they are luxuries in other regions, said Izidine Pinto, senior climate researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, who was not involved in this study.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate Now“If you are well off, you have air conditioning, you can survive,” he said. “But most of the people living in regions of the global south, where they don’t have means, they don’t have air conditioning, they don’t have fans.”

Extreme temperatures can also have secondary—but still devastating— health impacts, he added. Prolonged high temperatures can increase the risk of crop failure, and even bring the risk of vector-borne illnesses, such as malaria, into regions previously unaffected by the diseases, like South Africa and Mozambique. More heat waves also mean more stress on energy infrastructure, Ayegbusi explained.

“There will be [a] need for more energy being used for cooling systems,” he said. “And most countries in Africa currently don’t even have a 24-hour power supply.”

The new research and the growing body of literature it adds to can help governments prepare for the coming increases in heat stress, said Kimutai, who did not contribute to the study. But even the new research might be underestimating the risk.

Continental-scale, on-the-ground observations, such as those from weather monitoring stations, are not nearly as common in Africa as they are in parts of North America and Europe. And these stations are often unevenly distributed and concentrated in “better-to-do economies within the African region,” Bobde said. When there’s a dearth of continuous, evenly distributed ground observations, climate scientists and meteorologists are increasingly defaulting to reanalysis products. These data products, which are fundamentally model outputs corrected with whatever available real-world observations exist, can fill in gaps to make continental-scale studies possible. But for reanalysis to be effective, it needs exactly what’s missing in Africa, Kimutai said—comprehensive real-world observations.

“[Reanalysis is] not good enough for the continent,” she said. “It underestimates heat waves completely.”

Underestimating the magnitude of a heat wave can be a problem for local governments that need to develop action plans to help their citizens prepare for unexpectedly dangerous temperatures and warn them about the delayed and unseen risks of extreme heat exposure.

“When people go to hospitals, they go for, for example, cardiac arrest or stroke, and that’s what is written: a stroke,” Pinto said “But what caused that stroke is not immediately seen. It might be because it was too hot.”

To reduce delayed health consequences, governments need to proactively and explicitly tell people “to take precautions, not go outside, not exercise, drink a lot of water, avoid alcohol, just stay in cool places,” Pinto said. But leaders can only do that if they can accurately predict the severity of a heat wave, which is not currently possible in many African countries. New weather monitoring stations added throughout the continent could enhance this type of research in Africa, Ayegbusi said, and aid in responding to extreme heat.

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,