Dust storms have always swirled through parts of North America, but they are becoming more unexpected and destructive and landing in places unfamiliar with the danger, scientists warn.

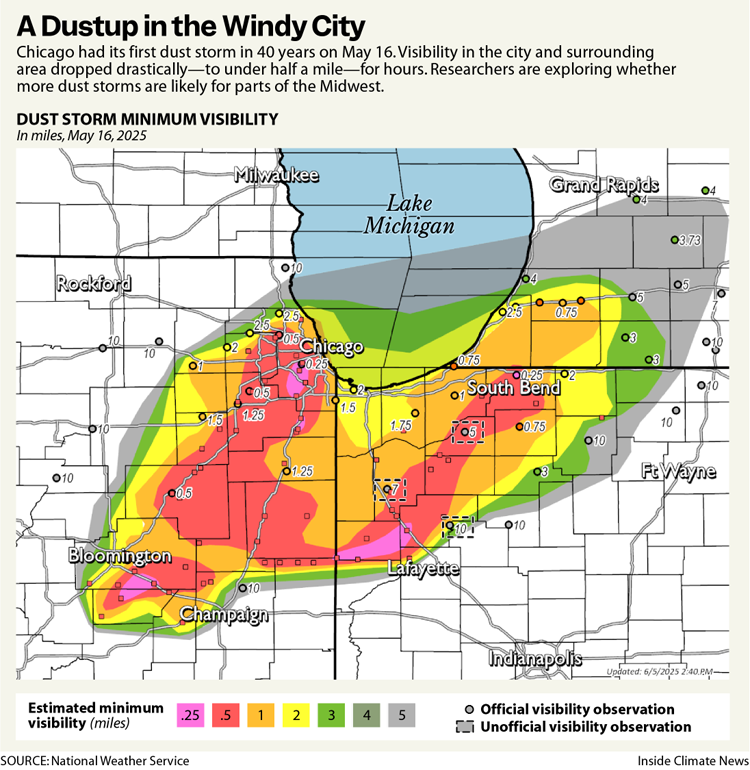

In May 2023, a dust storm stalled over parts of central Illinois, disorienting more than 80 motorists on Interstate 55 who crashed into each other, leaving eight people dead and 37 hospitalized. In March this year, Kansas found itself swallowed in a dusty rush of wind that covered Interstate 70, killing eight people in a 71-car pileup. A few months later, Chicago was engulfed by its first torrent of throat-choking dust since 1985. No one was injured in that May storm but visibility was near zero for hours.

In all these cases, the dustups followed a similar script. Thunderstorm winds churned up soil from plowed-open fields and carried it for a short distance. Dust billowed violently, giving people little warning. Scientists from the region are now reviewing and pursuing research to consider whether the ruptures are the start of a new normal for parts of the Midwest.

Agriculture practices have been slow to adapt or anticipate the risks of climate change and particularly droughts, some studies have shown. Dry-tilled fields, notably before spring plantings, are vulnerable to more intense seasonal winds. Kansas knows from history the wreckage of harsh and relentless gusts. A hundred years ago, parts of the Plains states lived through the disastrous Dust Bowl before agricultural irrigation and adaptations were in place.

Will this generation, across the Midwest, have to reckon with a new dust risk rooted in climate change?

Drivers of Dust

Both 2023 and 2025 storms in Illinois happened early in the growing season. In 2023, the winds swept up dust from open fields, just south of Springfield. As it moved eastward, the wind speed rose to roughly 60 mph. Nearby Interstate 55 was in its path.

Eliot Clay, director of the Association of Illinois Soil & Water Conservation Districts, lives near Interstate 55. He was worried shortly before the disaster. “I remember a couple days prior noticing how much dust was in the air, like you could see it,” Clay said. “I remember thinking if this wind shifts and it goes from west to east, there is a major interstate right there. And sure enough, all of that happened a couple days later.”

Complex factors caused the Interstate 55 storm, said Jonathan Coppess, director of the Gardner Agriculture Policy Program at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and former administrator of the Farm Service Agency at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. A cold spring season coincided with drought, creating a lot of dust in the fields. The planting season started late and high winds descended. Then there was a bit of bad luck.

Coppess and a team of researchers from the University of Illinois, Texas A&M University and Cornell University studied the 2023 incident and described how the dust storm crossed I-55 and collided with a tree line—a defense often planted close to highways to prevent dust storms and blizzards.

But there was only one tree line along this part of the highway and it, unfortunately, was on the wrong side of the road for this storm.

“If the wind had come from the other direction, there would have been no accident simply because that windbreak would have worked,” Coppess said. “The most interesting to me is how that clump of trees, which is designed basically as a windbreak, ended up concentrating dust right in the accident spot.”

Thomas E. Gill and a team of colleagues in Texas have calculated that the economic risk of such storms is rising and that the U.S. could be losing around $154.4 billion annually due to wind erosion and dust, according to a review of data from 2017.

That number, which includes losses in agriculture and renewable energy, health costs, car accidents and other factors, was based on the limited data they could gather. Gill, an environmental scientist at the University of Texas at El Paso, said the real toll is likely higher.

Gill is one of the leaders at the Dust Alliance for North America, an inter-university partnership that aims to promote more dust-related research and its practical application across the United States and other countries. The accident in Illinois isn’t the only recent dust storm that caused blinding loss of visibility and car crashes, Gill said.

Accidents increasingly have been recorded across the Great Plains and the Pacific Northwest.

Growing dust storms aren’t necessarily warning of a repeat of the Depression-era tragedy, he said. “Rather than seeing a large wholesale dust bowl over a lot of the plains like happened in the 1930s, you might see a bunch of mini dust bowls here and there in various different states and regions,” said Gill, who has published several studies on atmospheric dust.

The United States has better soil and water protection efforts than a century ago. But, he said, “there’s no question that climate change is one of the major drivers of dust.”

Drought and Gusts

So how does a dust storm erupt?

Air is constantly filled with soil and sand particles that move around, playing a key role in spreading minerals. Plants in North and South America are partly dependent on the dust carried all the way from the Sahara Desert by Atlantic winds. But droughts and strong winds can complicate dust movements, leading to serious harm.

A dust storm is an occurrence that reduces visibility to less than one kilometer, according to the World Meteorological Organization, a United Nations agency that promotes international cooperation on atmospheric science, climatology, hydrology and geophysics. Periodic exposure to dust storms leads to long-term health risks, including cardiovascular disease and lung conditions like asthma.

Last year, the U.N. General Assembly declared 2025 to 2034 as the Decade on Combating Sand and Dust Storms. With this initiative, U.N. officials are trying to raise awareness of dust threats and urge more international cooperation.

Dust formation is a mechanical process. It usually happens in two ways, said Barry Baker, a physical research scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Air Resources Laboratory.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowWind can make a large dust particle roll on the ground, forming the particles into larger masses. That formation is called a creep.

The other process is called impaction, where the wind is high enough to raise particles off the ground until they fall to earth with calamity. “Whenever it crashes, it throws a bunch of other particles up in the air,” Baker said, “and that then basically cascades more and more and more.”

The increased unpredictable heavy rains and extreme droughts create potential for more dust events, Baker said. These events happen in spring and fall, when the soil is often barren, but now they have started to “even out” throughout the year, he added. So big dust storms are happening earlier and later in the season than they used to, he said.

“When we see dust storms happen, that is the top soil that has taken thousands of years to build up, literally blowing away.”

— Eliot Clay, Association of Illinois Soil & Water Conservation Districts

U.S. farmers have protected their soil with cover crops over the years, notably after the 1930s and in recent decades. But strong spring winds have arrived before planting in the past couple of years, not just confusing drivers on Illinois’ interstate but confounding farmers. The quality of soil is at risk.

“The soil is so good [in Illinois] because it had thousands of years of perennial tall grass prairie on it,” said Clay, who represents the 97 soil and water conservation districts in Illinois. “And that system that existed naturally meant we had root systems that were going deep into the ground.”

“When we see dust storms happen, that is the top soil that has taken thousands of years to build up, literally blowing away,” Clay said.

Altering the Landscape

Anna Gannet Hallar, professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah, was part of a research team that in 2020 examined space satellite data of expanded farmland within the Midwest/Great Plains region. They explored how climate change and land use has been “altering the landscape, producing increases in windblown dust.”

Hallar said most observed dust increases were significant, linked to land being tilled more often. The Great Plains region faces an increased risk of dust storms and possible desertification, Hallar said.

“We saw doubling [of dust in the air] over 20 years, and we were able to show that that doubling was associated with changes in land use,” Hallar said.

Evan Thaler, a soil health researcher at Oregon State University, said 30 percent of the top-level soil in the Midwest has been lost. “What’s driving the majority of erosion across the landscape is just the mechanical movement of soil by people plowing over and over and over,” Thaler said. “If we’re tilling a lot, it makes the soil susceptible to any type of erosion.”

As the climate crisis accelerates across the planet, it creates conditions for multiyear droughts in many regions, including the United States. Such droughts endanger both plants and soil—which simply doesn’t have enough time to regenerate. Some multiyear droughts turn into megadroughts—among the most severe in centuries.

The U.S. Southwest is currently going through its most intense megadrought in 1,200 years.

Zack Leasor, director of the Missouri Climate Center at the University of Missouri and the state climatologist, said multiyear droughts can lead to much more devastating effects than a one-time event. It takes time for water reservoirs, plants and industry to recover. With a year-after-year drought, they get no break, he explained.

After the Dust Bowl, the Great Plains agriculture industry recovered and relies now on irrigation from underground water sources, Leasor said. That irrigation system helps confront droughts, but the increasing number of megadroughts as climate change worsens will test that adaptation, Leasor warned.

“While groundwater can be kind of a Band-Aid to get you through a drought, it can also turn into a long-term water supply problem,” Leasor said. Groundwater is used up much faster than it can be replenished, he said, and repetitive drought lets less and less moisture from rain reach down into natural underground reservoirs.

While existing irrigation technologies can help, they aren’t going to solve the growing drought problems, Leasor said.

Gill and his research colleagues, meanwhile, found that human casualties from dust storms are roughly on the same level as casualties from hurricanes, thunderstorms or wildfires. Frequently that’s happened in deserts and farm country—places that don’t receive a lot of press coverage.

“A lot of the deleterious effects of dust, of the casualties, as you say, caused by dust, are out of sight, out of mind,” Gill said. “I don’t think we yet really understand or realize as a society in the United States the full risks that dust poses.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,