Nearly 40 percent of the thousands of deaths that can be attributed to high heat levels in cities could have been avoided through increased tree coverage, a recent study from Barcelona’s Institute of Global Health found.

Past studies have linked urban heat with increased mortality rate and hospital admissions for adults and children. This link between high temperature and mortality holds both in times of extreme and moderate heat. In addition to conducting a similar analysis between urban heat and mortality, the Institute of Global Health’s study went on to estimate possible reductions in temperature and mortality that may result from increased tree coverage.

To establish the reduction in heat-induced urban mortality from increased tree coverage, researchers first compared mortality rates in warmer urban areas with mortality rates in cooler non-urban areas. This allowed them to estimate the relationship between increased temperature and mortality in urban areas. Researchers were then able to estimate the degree to which planting more trees could decrease temperature and thereby urban mortality rates. Specifically, a 30 percent increase in tree coverage could lead to 40 percent fewer deaths from urban heat.

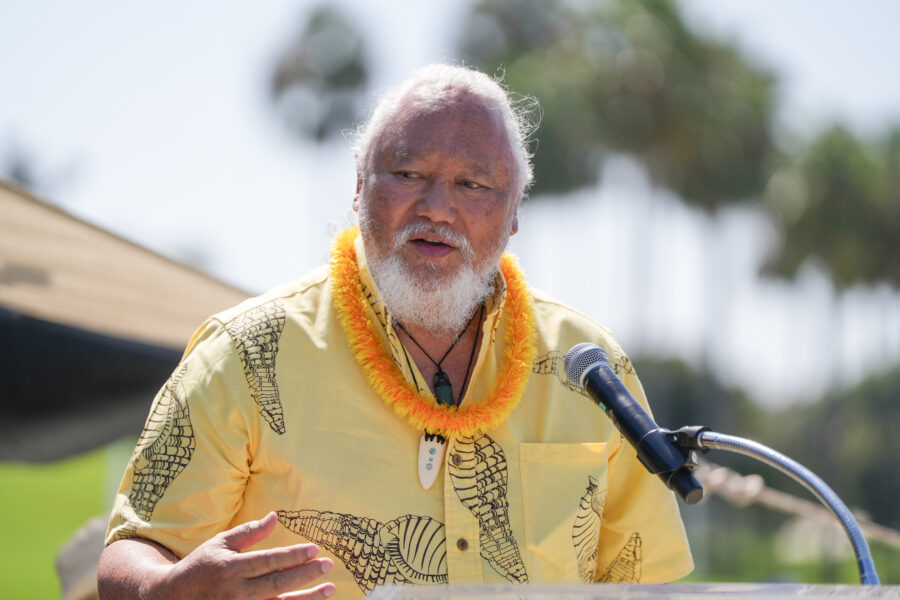

Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, a research professor at ISGlobal and the study’s senior author, said the strength of their paper is in its holistic analysis of the issue. By linking heat, mortality and urban greening, the paper is able to stand at the “nexus of the climate crisis, urban forestry, health and urban planning,” said Nieuwenhuijsen, who also directs ISGlobal’s urban planning, environment and health initiative.

Through analyzing urban greening’s impact on heat-induced mortality, the paper is uniquely able to recommend solutions. Patrick Kinney, a professor of environmental and urban health at Boston University who was not involved in the study, said that while the paper’s estimated impacts of planting more trees aren’t exact, they are useful in illustrating to “policymakers that there are potential benefits of intervening in the urban space and changing land use.”

“This is a good example of how public health information can be integrated into climate planning, and urban planning,” said Kinney. “And I think that’s something that we ought to do more of, because as long as we’re taking action to combat climate change, we ought to be at least thinking about how we can do it in a way that’s also promoting health and equity.”

As cities get warmer with climate change, many are trying to figure out ways to reduce the temperatures and adverse health impacts, Kinney said, adding that the study’s findings are “very relevant to what lots of cities are doing to try to adapt to climate change, to make climate change less impactful on the local community.”

Nieuwenhuijsen said that mitigating heat-induced urban mortality requires multiple avenues of action, as well as patience. He explained that about 85 percent of the fuel emitted by cars is emitted as heat, while “only 15 percent is used to move the car forward. So you’re also looking to see, can I reduce other things that actually produce the heat?” Niuewenhuijsen suggested the creation of more bikeable and walkable cities to counteract these effects of car travel.

In the study, Nieuwenhuijsen and colleagues proposed “replacing impervious surfaces with permeable or vegetated areas” and increasing the use of light colors on city roofs and walls as a means of possibly reducing urban heat. However, the most cost-effective and simple method of combating urban heat may be to simply plant more trees in cities and preserve those that already exist, the study said.

This story is funded by readers like you.

Our nonprofit newsroom provides award-winning climate coverage free of charge and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep going. Please donate now to support our work.

Donate NowAs far as trees go, Nieuwenhuijsen said that “it’s not as much about planting more trees, but in particular, also preserving the current trees that we have in the city.” Of those new trees that are planted, about “half of them die within two years and it takes about 50 years to grow full trees,” he said.

Still, Nieuwenhuijsen maintains a tempered optimism regarding public response to the study. “There is a move toward making the cities more for people: making them more livable, making them healthier, also making them carbon neutral, of course. So I think there is a general improvement under this direction,” Nieuwenhuijsen said. “Of course, it’s still a bit too slow. I mean, that’s the problem. The pace is not as fast as what we’re hoping for.”

About This Story

Perhaps you noticed: This story, like all the news we publish, is free to read. That’s because Inside Climate News is a 501c3 nonprofit organization. We do not charge a subscription fee, lock our news behind a paywall, or clutter our website with ads. We make our news on climate and the environment freely available to you and anyone who wants it.

That’s not all. We also share our news for free with scores of other media organizations around the country. Many of them can’t afford to do environmental journalism of their own. We’ve built bureaus from coast to coast to report local stories, collaborate with local newsrooms and co-publish articles so that this vital work is shared as widely as possible.

Two of us launched ICN in 2007. Six years later we earned a Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, and now we run the oldest and largest dedicated climate newsroom in the nation. We tell the story in all its complexity. We hold polluters accountable. We expose environmental injustice. We debunk misinformation. We scrutinize solutions and inspire action.

Donations from readers like you fund every aspect of what we do. If you don’t already, will you support our ongoing work, our reporting on the biggest crisis facing our planet, and help us reach even more readers in more places?

Please take a moment to make a tax-deductible donation. Every one of them makes a difference.

Thank you,